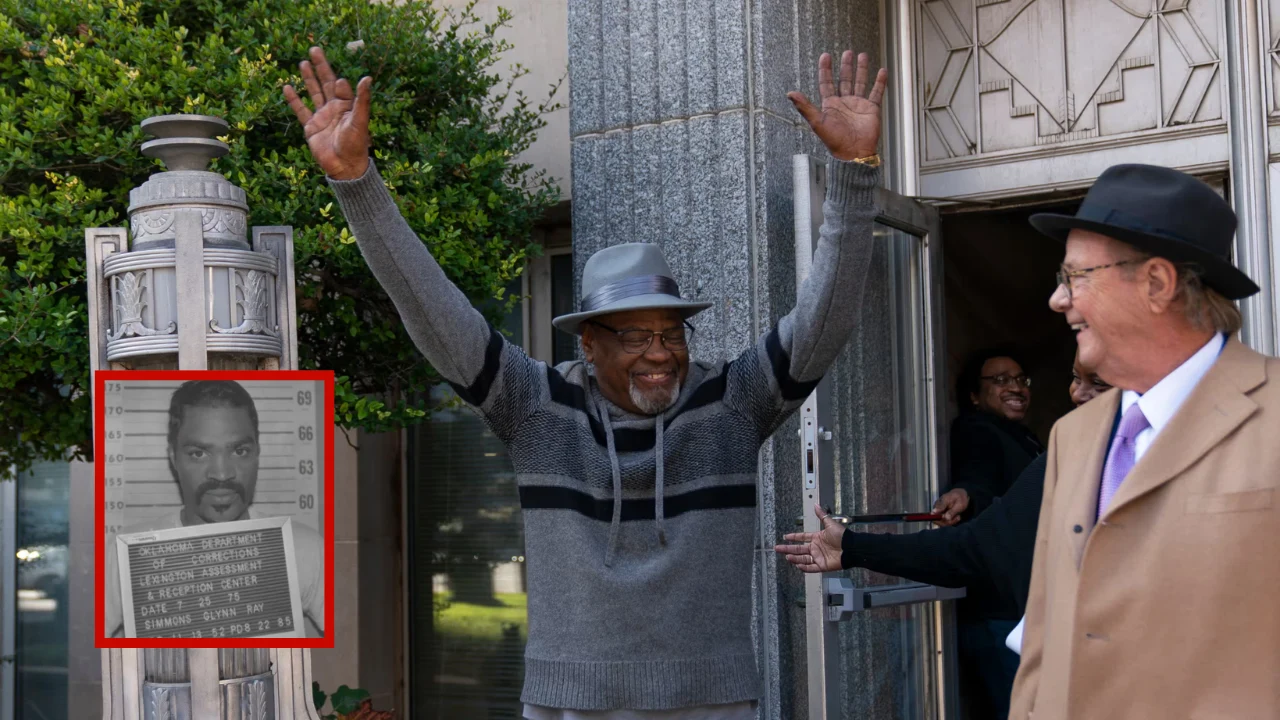

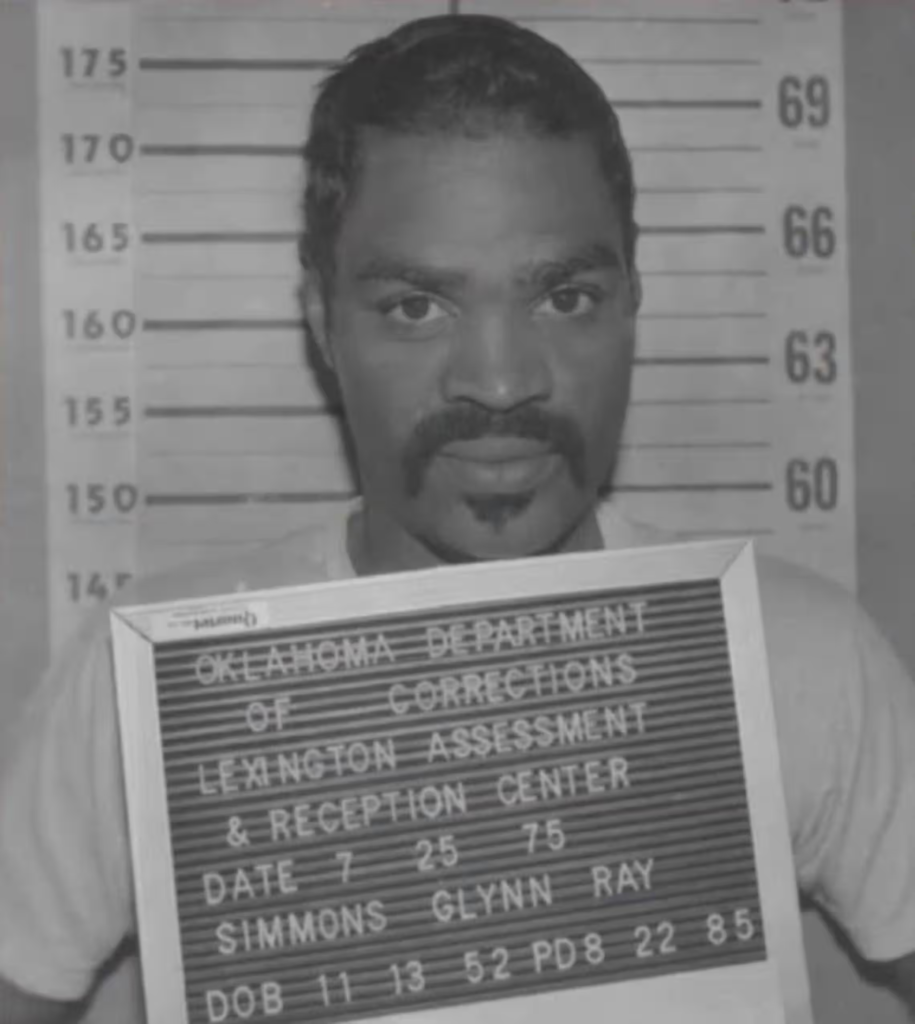

In 1975, Glynn Simmons was 21 years old, newly arrived in Oklahoma from Louisiana, and searching for work. Six days after his arrival, he was arrested for robbery a charge that was quickly dropped. But before his release, police asked him to stand in a lineup as a favor. He agreed, unaware that he had the right to refuse. That single decision would cost him nearly half a century of his life.

Simmons would go on to spend 48 years, 1 month, and 18 days behind bars for a 1974 liquor store murder he did not commit. His wrongful conviction, based on fabricated evidence, suppressed documents, and a false eyewitness ID, now stands as the longest-known wrongful incarceration in U.S. history.

No Evidence. No Justice.

Carolyn Sue Rogers, a 30-year-old store clerk, was shot in the head during a robbery in Edmond, Oklahoma, on December 30, 1974. Simmons wasn’t even in the state at the time twelve witnesses placed him in Louisiana that night, playing pool and celebrating the holidays.

Yet despite having no physical evidence and no forensic link to the crime, prosecutors pressed forward. The case hinged on one thing: the testimony of an 18-year-old eyewitness, Belinda Brown, who had also been shot in the head during the incident. Brown initially told detectives her memory was unreliable, saying her mind was “jumbled.” She never identified Simmons in any lineup. In fact, she pointed to other men in eight different lineups, none of them Simmons.

Crucially, a police report confirming this misidentification was never shared with the defense. Instead, the prosecution submitted a single-page document falsely claiming Brown had identified Simmons and his co-defendant, Don Roberts. The document was later exposed as a likely fabrication.

Simmons was convicted by an all-white jury after a trial that lasted less than three days—including jury selection and deliberation. One Black man had been on the jury panel, but he was dismissed.

In June 1975, Simmons was sentenced to death by electrocution. He was 22 years old.

Survival on Death Row

After his 1975 conviction, Glynn Simmons was sentenced to die in Oklahoma’s electric chair. For two years, he lived on death row—a place of constant psychological torment. Inmates were confined to their cells 24 hours a day, with rare, 15-minute breaks to shower three times a week. There was no yard time. No sunlight. Just endless isolation and the looming threat of execution.

Simmons’ cell was located near the execution chamber. He knew the chair was just down the hallway, and he could hear the preparations when others were taken. The stress took its toll. “I watched men go insane. I felt myself slipping sometimes,” he said. “I had anxiety attacks that would come out of nowhere.”

To survive, Simmons developed a coping mechanism he described as “temporary insanity”—brief mental escapes where he imagined conversations with people who didn’t exist. “You and your imaginary friends,” he said. “It’s like a vacation from reality. You eventually come back, but those little breaks help you keep going.”

This was all for a crime he didn’t commit, with no physical evidence tying him to the scene. And yet, for years, the justice system left him there—waiting to die.

Learning the Law to Fight the System

When Simmons first entered prison, he could barely read or write. “I couldn’t understand most of what was in my case files,” he later recalled. But prison had libraries—and he used them.

He taught himself to read using dictionaries and legal books. Other inmates helped him understand court procedures. Over time, Simmons transformed himself into a jailhouse lawyer, filing motions, writing letters, and relentlessly pursuing the truth of his case.

He wasn’t just focused on himself. Simmons began teaching other inmates to read. When a man in the cell next to him admitted he couldn’t read the letters from his family, Simmons said, “Well, I’m not that good either. Let’s figure it out together.” That moment grew into a literacy circle that helped dozens of men behind bars.

He also mentored younger prisoners, warning them about the traps of the system and encouraging them to educate themselves. “I learned that giving people hope helped me hang onto mine,” he said.

Despite overwhelming odds, he slowly pieced together the truth about his own case. He tracked down old evidence, contacted journalists, and eventually hired a private investigator. That investigator would discover crucial police reports—including the original lineup form that proved the eyewitness never identified Simmons. It had been withheld at trial.

The police had suppressed exculpatory evidence. Simmons had to find it himself.

A Life Sentence Without a Crime

In 1977, Simmons’ death sentence was commuted to life in prison after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling overturned Oklahoma’s capital punishment statute. He was spared execution—but not injustice. The system that failed him once simply kept him locked away.

He applied for parole repeatedly. Every time, he was denied. The reason? He wouldn’t confess. “They said I lacked remorse,” he explained. “But how can I express remorse for something I didn’t do?”

The state’s logic was cruel and circular: if you don’t admit guilt, you stay in prison. But admitting guilt would erase the very foundation of his innocence.

Inside, Simmons endured a prison system marked by violence, disease, and despair. He watched dozens of inmates die from illness, suicide, and violence. Some were his friends. Others were just names he never got to know.

He missed every family event—birthdays, funerals, holidays. His youth disappeared behind bars. When he entered prison, he didn’t even have a beard. When he left, he had grandchildren and great-grandchildren he had never met.

The years stacked up, but justice remained distant. His case sat ignored for decades—until new evidence finally came to light.

Freedom with a Price

In July 2023, Simmons walked out of prison a free man. But he was also a man in pain—mentally and physically. A few months before his release, he had been diagnosed with stage 4 liver cancer. He had not received chemotherapy in prison. The cancer had spread.

Despite being officially declared innocent in December 2023, Oklahoma offered him just $175,000 in compensation—the maximum allowed by a state law that hadn’t been updated in 20 years. That’s about $3.60 per day for the 17,568 days he spent behind bars.

“It’s a mockery,” Simmons said. “They paid private prisons $48 a day to keep me locked up, and they want to give me a fraction of that when they let me go? It doesn’t add up.”

He sued the City of Edmond and the estate of Detective Anthony Garrett, the officer who led the investigation and hid the exculpatory evidence. In early 2024, the city settled the lawsuit for $7.15 million—without admitting fault. That brought his total compensation to $7.325 million, or about $417 a day. Still far less than what private prisons earned for his incarceration.

Simmons received no state-funded medical care upon release. He had no housing, no job prospects, and no government support. For months, he relied on a GoFundMe campaign that raised more than $350,000, including several large anonymous donations.

Even today, he struggles to adapt to modern life. Simple things like using a smartphone, applying for healthcare, or understanding banking systems feel foreign. He missed 49 years of life lessons that most people take for granted.

“I’m 71 years old, and I’m just now learning how to live,” he said.

Still, he harbors little bitterness. “I’m not going to waste the time I have left being angry,” he said. “I’ve been to the darkest extreme. Now I want to experience the brightest.”

Adjusting to a Changed World

After 48 years in prison, Simmons found modern life overwhelming. He struggled with using debit cards, understanding bank accounts, and learning the basics of smartphones and online payments. “I feel dumb,” he once told his cousin, who reassured him: “You’ve been gone, Glynn. How would you know?”

He placed food meant for the refrigerator into the freezer. He confused CashApp with his bank. Technology, culture, even grocery stores—all of it felt foreign.

Yet despite those struggles, Simmons remained resilient. Friends and relatives helped him furnish his home, pay rent, and attend to daily needs.

Battling Cancer and Bureaucracy

Simmons underwent surgery in summer 2024 to remove the cancer, but it returned. He resumed chemotherapy, battling fatigue and side effects while rebuilding his life.

As of mid-2025, he had not received a formal mental health evaluation, despite requesting it after his release. His cousins voiced concern, noting signs of trauma and institutional conditioning.

“That place raised him,” said one cousin. “He isn’t who he could have been.”

Without state support, Simmons relies on his support network. “If it weren’t for my family,” he said, “I’d probably be under one of them bridges y’all pass by every day.”

Building a Future

Last summer, Simmons launched a business: Free Man’s Food Truck a dream born during late-night prison talks with cellmate-turned-chef Andre Armstrong. The truck serves catfish, hotdogs, burgers, and fries in northeast Oklahoma City.

The name “Free Man” came from a moment just after Simmons was released. As reporters shouted questions, one voice called out: “Where you going, free man?” It stuck.

He plans to expand into Free Man Industries, offering lawn care, podcasting, and job training. One initiative, No Hate, will focus on reducing recidivism among former inmates.

Legislative Change

In May 2025, Oklahoma passed HB 2235, which increased wrongful conviction compensation to $50,000 per year served, $50,000 for each year on death row, and $25,000 per year on parole. It also removed eligibility restrictions for those who had pleaded guilty.

But the law is not retroactive. Simmons won’t benefit.

“We want to provide compensation with dignity,” said bill sponsor Rep. Cyndi Munson. But for Simmons, dignity came too late.

Looking Ahead

Now 71, Simmons lives with his son and continues to receive support from family and friends. He has reconnected with grandchildren and great-grandchildren. He’s seen an NBA game, gone fishing, and stared up at the stars—things he couldn’t do in prison.

He recently returned to the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board—not for himself, but to advocate for someone else.

Freedom “agrees with me,” he says. He’s still fighting cancer. He’s still fighting for justice. But he’s also focused on building something new.

“When the Lord sets you free, you are free indeed,” he says. “So I am free indeed in all aspects, regardless of what they say on a piece of paper. And as far as I’m concerned, I’ve always been free, you know?”