On January 7, 1969, Harvard student Jane Britton didn’t show up for her General Exams. Later that day, she was found murdered in her Cambridge apartment. Her case stayed unsolved for nearly 50 years until new DNA testing finally revealed who killed her.

The Last Known Hours

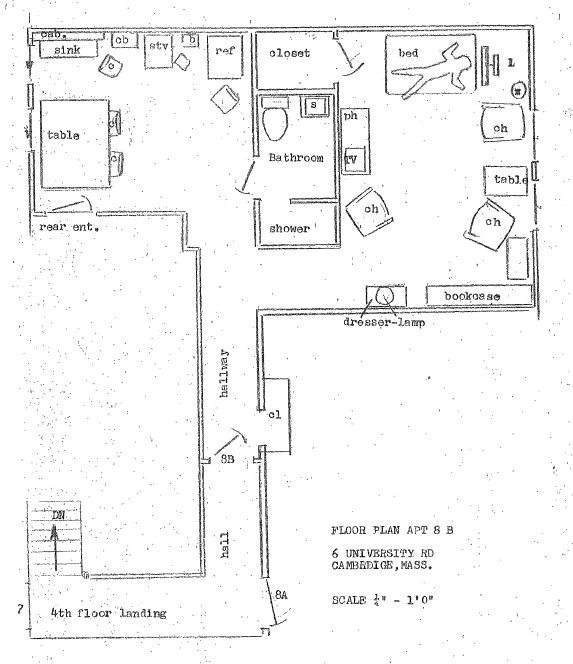

On the night of January 6, 1969, Jane Britton spent the evening with her boyfriend, James Humphries, and classmates. They ate dinner, then headed to Cambridge Common for a short round of ice skating before returning to her apartment at 6 University Road around 10:30 p.m.

James stayed about an hour. Nothing seemed off. Jane talked about feeling nervous for her General Exams the next morning, a major milestone in Harvard’s archaeology program. When James left around 11:30 p.m., she appeared focused and ready for the day ahead.

Minutes later, Jane stepped next door to Dawn and Jill Mitchell’s apartment. The three shared a quick glass of sherry. At 12:30 a.m., she said goodnight and returned to her room to sleep.

No one saw her alive again.

Discovery

By noon on January 7, Jane had missed her General Exams. James called her twice that morning with no answer. As soon as he finished his own exam at the Peabody Museum, he walked the 15 minutes to her building, trying to convince himself she was sick or overslept both unlikely for her.

At her door on the fourth floor, he knocked twice. No response. Dawn Mitchell stepped into the hallway, equally concerned. He urged James to check inside; Jane’s door was almost always unlocked.

James entered first. A blast of cold air hit him the kitchen window was open. The apartment looked unchanged from the night before. Then he looked into her bedroom and froze. Jane lay face-down on the bed, her nightgown pushed above her waist.

He backed out immediately and asked Jill Mitchell to look instead. She stepped inside, saw the scene, and hurried back out, shaken. Dawn went next. Under a sheepskin rug and a fur coat covering her head, he found Jane’s body.

She had been murdered.

The Crime Scene

Police arrived within minutes. Inside Jane’s apartment, almost nothing was disturbed. Money, jewelry, and valuables were untouched. Her cat and pet turtle were unharmed. The room reflected her usual lived-in clutter, not a struggle.

The only disruption was on the bed. Jane had been struck in the head with a sharp-edged or pointed weapon. Multiple blows caused deep lacerations; one was forceful enough to fracture her skull. No weapon was found.

Most blood was confined to the bed, and there were no signs she fought back. Detectives concluded she had likely been attacked while asleep. She had also been sexually assaulted, though police withheld that detail from the public for months.

Two windows were open the kitchen window James noticed, and Jane’s bedroom window. Residents told police the building’s heat was so erratic that many tenants slept with windows open even in winter, leaving investigators unsure whether entry occurred there or not.

Nothing at the scene, except the rug and fur coat covering her head, gave them a clear direction.

Early Leads and Confusion

Detectives began with the people who last saw Jane. James said they returned to her apartment around 10:30 p.m., and he left at 11:30 p.m. The Mitchells confirmed Jane visited them for a quick drink and went back to her room at 12:30 a.m. That gave investigators a rough window the murder likely occurred 10–12 hours before discovery.

Two outside witnesses added fragments. A 7-year-old girl reported hearing someone on the fire escape at 9 p.m., but that time didn’t fit Jane and James weren’t even home yet, and neighbor Dawn Mitchell had entered her apartment around then without noticing anything wrong. Another witness claimed he saw a man, about six feet tall and 170 pounds, running from the building at 1:30 a.m. The description was vague, and it was raining, making it impossible to confirm any link.

Attention shifted to the building itself. Six University Road had long-standing security failures broken locks, open entrances, and windows that could be forced easily. Jane’s door lock had never worked properly. Tenants said anyone could walk in off the street.

Record checks provided one more unsettling fact a graduate student had been murdered in the same building in 1963. Police publicly dismissed any connection, but the coincidence widened public fear.

Despite early effort, investigators had no motive, no weapon, and no suspect who fit the physical evidence. The case stalled almost immediately.

The Red Ocher Twist

Within hours, reporters surrounded the building. By the next morning, Jane’s murder pushed national headlines, even overtaking coverage of the Sirhan Sirhan trial. Her academic background, her family’s ties to Radcliffe, and the circumstances of her death created intense public pressure for answers.

Then a single detail ignited sensational speculation red ocher. The reddish-brown pigment used in painting and in some ancient burial rituals was found in several spots in Jane’s room and on her body. Because Jane was an archaeology student, some observers theorized her killer staged a ritualistic scene.

Detectives could not confirm whether the pigment mattered or simply came from her art supplies. But the media narrative ran unchecked. Rumors suggested a classmate with archaeological knowledge might be involved.

As coverage spiraled, Cambridge Police Chief James Reagan imposed a news blackout. No further information would be released without his approval. Investigators admitted privately they had “no handle” on the case, but publicly, the flow of facts stopped.

The red ocher theory, despite lacking evidence, shaped public perception for decades and distracted from the case’s core problem authorities still had no viable suspect.

A Second Murder

In early February 1969, a new killing rocked Cambridge. Ada Bean, a 50-year-old widow living less than a mile from Jane, was found bludgeoned in her bed. Like Jane, she lived alone in a building with weak security. She appeared to have been attacked in her sleep, her nightgown pushed up, and a blanket placed over her head.

The parallels were immediate and unnerving. Two women. Same city. Same method. Same vulnerabilities.

Public pressure surged again, but investigators hesitated. Despite the similarities, they said there wasn’t enough evidence to link the murders. No shared suspect. No matching weapon. No forensic connection.

While the Ada Bean case captured attention, a grand jury reviewed evidence in Jane’s case. Detectives hoped sworn testimony might reveal a pattern or a missed detail. Months passed. Nothing materialized. The grand jury ended without a vote or a suspect.

By mid-1969, both murders slipped from headlines. Tips dried up. Leads collapsed. Jane Britton’s file grew cold, then colder. For the next two decades, the case drifted with no new direction just unanswered questions and an unsolved killing in the shadow of Harvard.

DNA Hope and a Breakthrough

In the 1990s, a fresh review of Jane’s case uncovered a rare advantage investigators had preserved semen from the crime scene, collected long before DNA was part of routine forensics. Early tests produced no match in the national CODIS database, and the sample was small, limiting what could be done.

A second test in 2006 also failed. With no suspect DNA on file and no remaining investigative leads, many assumed the case would remain unsolved.

Outside pressure changed that. Beginning in the mid-2010s, several people most prominently former New Yorker writer Becky Cooper and retired journalist Michael Widmer filed repeated requests for the case records. The Middlesex District Attorney’s office denied them, insisting the case was “still active,” even though nothing new had occurred in decades.

Their persistence forced officials to demonstrate progress. In 2018, the DA ordered another round of DNA testing using more advanced methods. This time, the match hit.

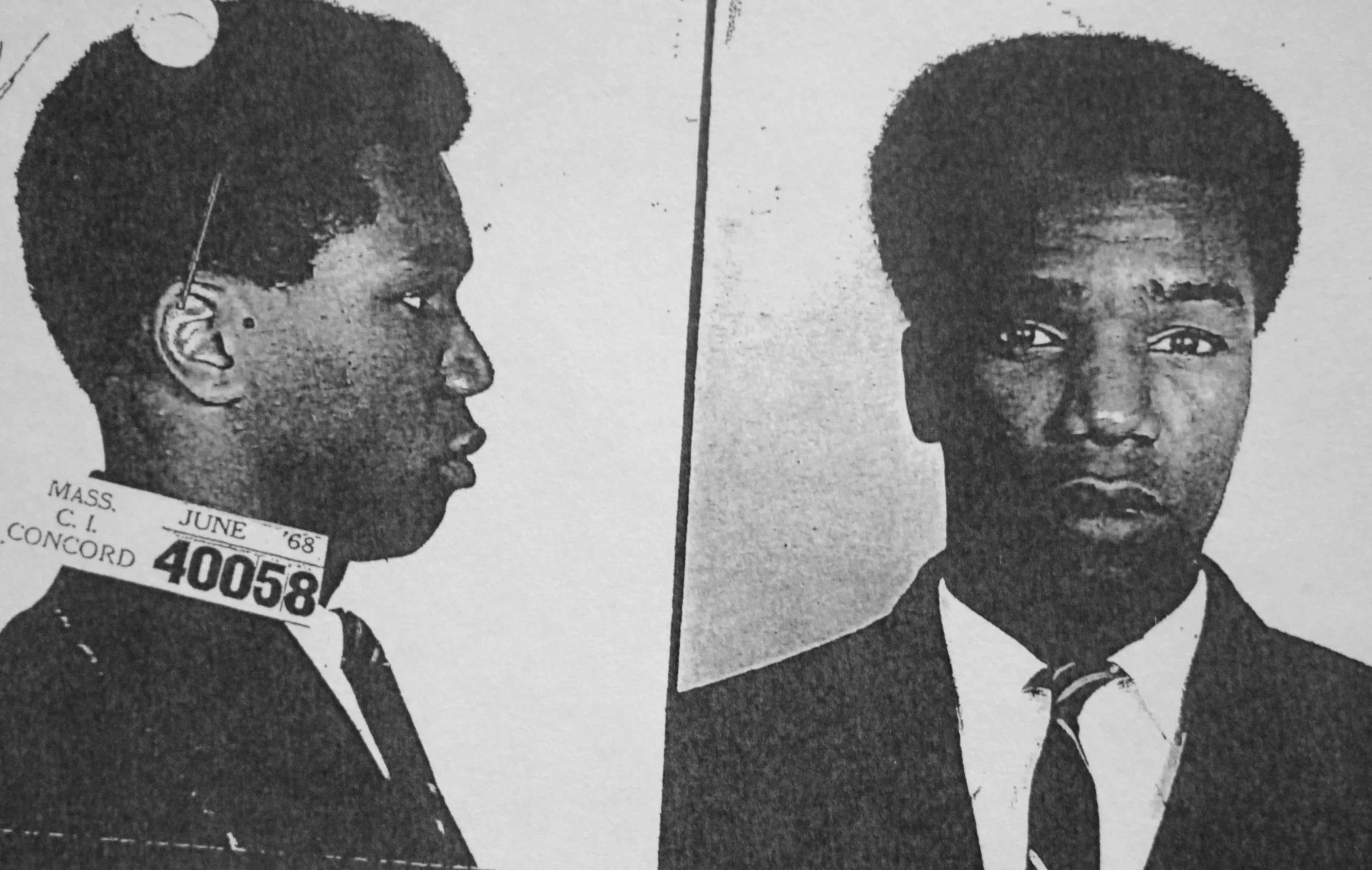

The killer was Michael Sumpter, a convicted serial rapist who had died in 2001. His DNA already tied him to two unsolved Boston murders from the early 1970s. He had lived and worked near Jane’s building in 1969, fitting the likely timeline and the witness description of a man seen running from the apartment at 1:30 a.m.

After nearly 50 years, Jane Britton’s case had its answer though some surrounding mysteries, including the parallel murder of Ada Bean, remained unsolved.

Aftermath

The 2018 announcement closed the longest-running unsolved murder in Middlesex County. Investigators concluded that Michael Sumpter followed Jane home, waited for James to leave, and entered her apartment via the fire escape before assaulting and killing her.

The sensational red ocher theory, which shaped public imagination for decades, proved irrelevant simply residue from Jane’s art supplies. And while a witness’s sighting of a man fleeing at 1:30 a.m. now aligned with Sumpter, the case resolved only after DNA technology advanced far beyond what was available in 2006.

Still, gaps remain. Authorities say Sumpter is not believed to have killed Ada Bean, despite the striking similarities. Her case remains open. So do lingering questions about how long the Britton investigation stalled and whether earlier DNA testing or greater transparency could have solved it years sooner.

What remains certain is that the search for Jane’s killer stretched across half a century waiting for science, pressure, and persistence to finally converge.