On November 1, 1955, United Airlines Flight 629 took off from Denver just before 7 p.m., carrying 44 people toward Portland and Seattle.

Eleven minutes later, the calm Colorado night exploded into fire.

A massive blast tore the aircraft apart in midair over Weld County. Debris rained across farmland near Longmont. Homes shook. Rescue teams rushed across fields, but there were no survivors. All 44 lives were gone within minutes.

What first appeared to be a tragic aviation disaster soon proved to be deliberate. Investigators would uncover that a bomb had been placed inside a passenger’s luggage and the man responsible was her own son.

The Bombing of United Airlines Flight 629

The day began like any other at Denver’s Stapleton Airport. United Airlines Flight 629 arrived behind schedule from Chicago due to earlier mechanical work, refueled, changed crew, and prepared to depart again. At 6:52 p.m., the DC-6B lifted off with 5 crew members and 39 passengers. Four minutes later, the crew made their final routine radio call. Nothing seemed wrong.

Seven minutes after that transmission, the quiet sky over Weld County erupted. Air traffic controllers saw two bright lights drop toward the ground, then a massive flash lit the clouds. The blast was so powerful that windows rattled across nearby towns. Farms miles away felt the shock.

On the Hopp family farm near Longmont, dinner stopped instantly. They heard the explosion, felt the house shake, and saw a fireball descending through the night. Engines roared overhead. Flaming debris streaked across their fields. Conrad Hopp and his family ran outside, then drove toward the falling wreckage, weaving around burning metal scattered in the dirt.

They weren’t the only ones heading toward the fire. Cars raced down country roads. Locals searched the darkness, hoping someone might be alive. Instead, they found devastation. Bodies lay across the farmland. In one field, an airplane seat rested upright, a passenger still strapped in. Fires burned across multiple impact points. The wreckage covered miles.

Emergency crews arrived fast. Police from Longmont, firefighters, Colorado State Patrol, and federal authorities converged on the scene. But rescue efforts turned to recovery almost immediately.

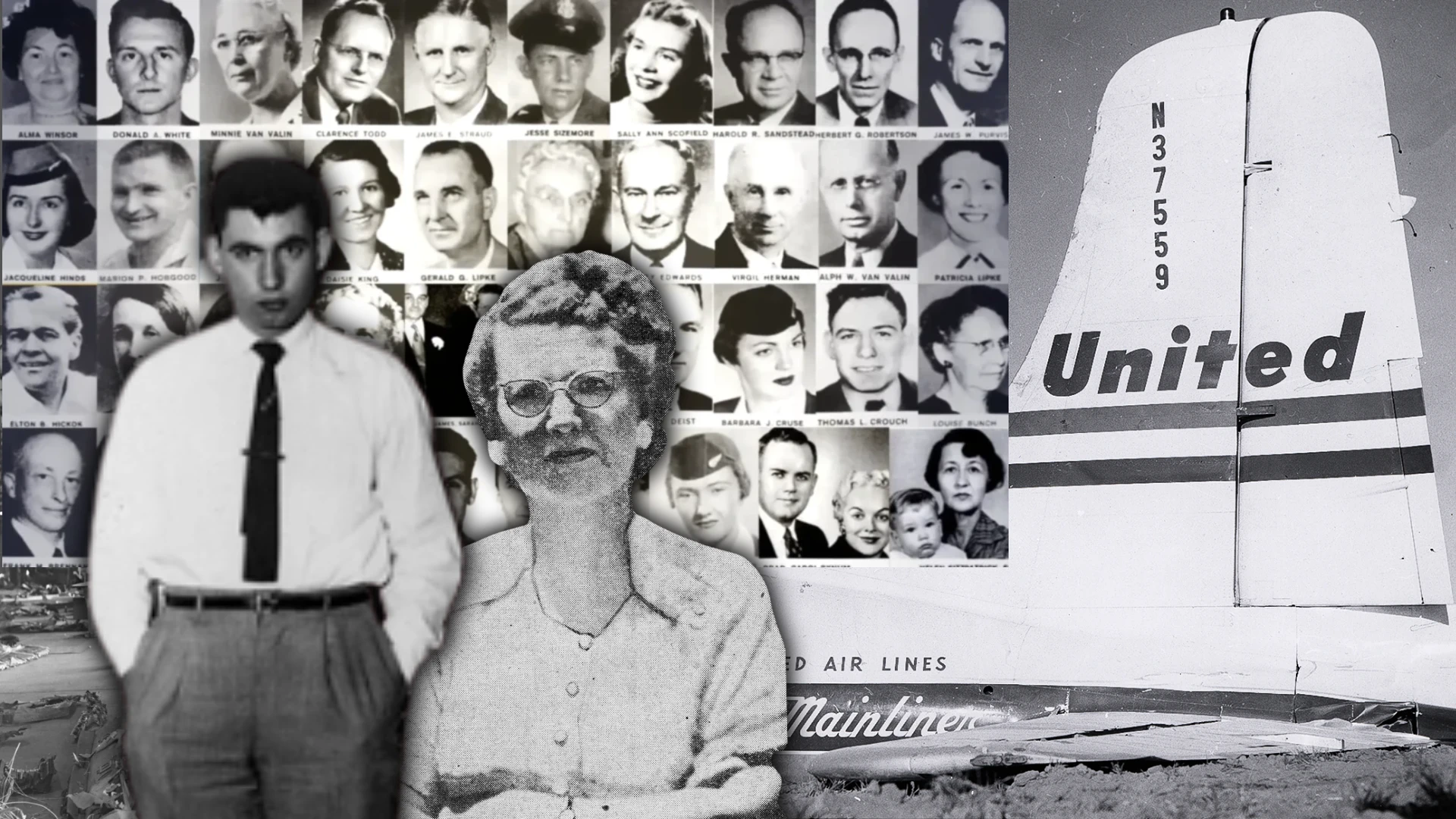

There were no survivors. All 44 people on board were dead.

Among the victims were 13-month-old James Fitzpatrick, traveling with his mother to meet his military father in Japan… 81-year-old Ila McLean, returning home to Portland… Anna (Alma) Winsor, flying to Tacoma to help care for her son battling polio… and Airman Second Class Jesse Seismore, heading back to his base in Alaska. Also on board were Brad and Carol Bynum, returning from their first wedding anniversary trip Carol was pregnant. Two off-duty United stewardesses, Sally Scoffield and Barbara Cruz, were traveling as passengers.

Several families lost both parents in the tragedy.

Investigators quickly measured the disaster’s scale. The debris field stretched roughly six square miles. The plane had broken apart in midair. Two large craters held major sections of the fuselage, engines, and wings. Smaller fragments were scattered everywhere. Fuel-fed fires burned for days despite nonstop efforts to put them out.

United Airlines confirmed the aircraft missing, and families received the news they feared most.

What no one yet knew was why the aircraft had disintegrated so violently. At first, speculation focused on mechanical failure. Maybe the earlier maintenance work mattered. Maybe weather or human error played a role. But as investigators walked the burning fields that night, one thing already stood out:

This didn’t look like a normal crash.

Investigating the Blast

As daylight returned to Weld County, investigators began turning chaos into evidence. The Civil Aeronautics Board, United Airlines experts, and the FBI mapped every piece of wreckage. Fields were divided into grids. Every fragment was photographed, tagged, and documented before removal.

Very quickly, one fact became undeniable: Flight 629 hadn’t crashed intact. It had broken apart in midair. The debris covered about six square miles, with some pieces discovered even farther away. The tail section had landed a mile and a half from the main wreckage, sheared cleanly from the aircraft. That pointed to an internal force, not pilot error.

Then came another clue smell. Local farmers familiar with explosives recognized it instantly. A sharp, firecracker-like odor hung in certain areas of the debris. Investigators noted it. The suspicion of sabotage grew stronger.

Wreckage was transported to a warehouse at Stapleton Airport. Inside, specialists built a wire-and-wood mock-up of the aircraft, attaching recovered pieces to recreate the fuselage. As they rebuilt, a pattern appeared. Damage intensified near cargo hold number four. The closer the fragments were to that section, the smaller and more shredded they became.

Chemical analysis confirmed what the field hinted. The FBI Laboratory tested soot-like residue found on wreckage and cargo. Results showed compounds consistent with dynamite. Investigators also recovered fragments of dry-cell batteries and wiring. Eleven small pieces appeared to come from a six-volt Eveready “hotshot” battery perfect for detonating an explosive device.

At that point, sabotage was no longer a theory. It was fact.

Then came a major breakthrough from pure chance. Earlier in the day, a baggage handler in Chicago had lost his keys inside cargo bay four. When the aircraft reached Denver, ground crews completely emptied that cargo section to search for them. Because of that, only luggage loaded in Denver ended up in cargo hold four when the plane took off.

So whoever planted the bomb had done it in Denver just hours before the explosion.

Investigators turned to luggage records. Only a few Denver-loaded bags were placed in that cargo pit. One suitcase immediately stood out a heavy, battered case belonging to a Denver woman named Daisy King. It had been so badly destroyed that almost nothing remained of it. That suggested one thing:

Her suitcase had been closest to the bomb… or had carried it.

From there, the investigation shifted. Not just to how the aircraft exploded.

But to who would want Daisy King dead and why.

The Son Behind It

The investigation soon centered on Daisy King, the Denver businesswoman whose destroyed suitcase matched the blast’s origin point. When agents began examining her life, one name kept emerging her son, John “Jack” Gilbert Graham.

Jack was born in Denver in 1932. His childhood was unstable. After his father died and his mother struggled financially, Jack spent years in institutions rather than at home. He never forgot it. Those early years built resentment that never went away.

As an adult, Jack drifted between jobs and schemes. He joined the Coast Guard underage, went AWOL for over 60 days, and was eventually discharged. In Denver, he forged checks, stole company money, fled the state, and was later arrested after a 100-mph chase in Texas. He received probation only because Daisy paid most of the stolen money back.

He eventually married, had children, and seemed settled when Daisy bought him a house and made him manager of her new drive-in restaurant. But trouble followed him. His pickup truck “stalled” on train tracks and was struck an insurance payout followed. Months later, a mysterious gas explosion damaged the restaurant. Investigators suspected fraud, but no charges came. Insurance paid again.

Jack’s relationship with his mother never stabilized. Witnesses described constant arguments, suspicion he was stealing from the business, and open hostility. At the same time, Daisy controlled much of his financial life. Her estate was worth a fortune. And she was heavily insured.

Then came the key discovery. Daisy’s luggage had been overweight at the airport. Jack had handled it. His wife admitted he placed a “gift” inside before the flight. Searches of his home uncovered extra insurance policies naming him as beneficiary, wires matching bomb components, and evidence he had bought dynamite and a timing device.

Jack eventually confessed. He admitted building a time bomb with dynamite, blasting caps, and a timer, placing it in his mother’s suitcase, and setting it to explode mid-flight. He planned for the aircraft to blow up over mountains so recovery would be difficult. A departure delay changed that.

His motive was simple and brutal. Money and revenge. He stood to gain from insurance and inheritance. And he felt no remorse. He later told psychiatrists that the number of people on board didn’t matter. It could have been a thousand.

With that, investigators had their answer. The tragedy of Flight 629 was not fate, weather, or mechanical failure.

It was one man’s deliberate act.

The Trial Begins

Jack Graham was charged with the murder of his mother. There was no federal law yet for bombing an airliner, so prosecutors focused on a single count that still carried the death penalty. Public interest exploded nationwide. His case became one of the first criminal trials ever televised in the United States.

Courtroom seats filled daily. Hundreds waited outside for a chance to watch. The prosecution presented overwhelming evidence chemical findings, bomb fragments, insurance policies, witness testimony, and Jack’s detailed confession. His defense offered little in comparison. Jack tried to recant, claiming pressure, but the facts matched his original statement too precisely.

The jury needed barely over an hour to decide. They found him guilty. The judge sentenced him to death. Jack showed no remorse, repeating that “Everybody pays their way and takes their chances. That’s just the way it goes.”

On January 11, 1957 just 14 months after Flight 629 exploded Jack Graham was executed in Colorado’s gas chamber.

Lasting Impact

The bombing of United Airlines Flight 629 exposed a terrifying reality. In 1955, there was no federal law specifically prohibiting the destruction of a commercial aircraft. Prosecutors could only charge Jack Graham with a single murder of his mother, not the deaths of all 44 people.

That changed because of this case.

On July 14, 1956, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed federal legislation that specifically made the bombing or destruction of a commercial aircraft a federal crime, with severe penalties including the possibility of the death penalty when lives were lost.