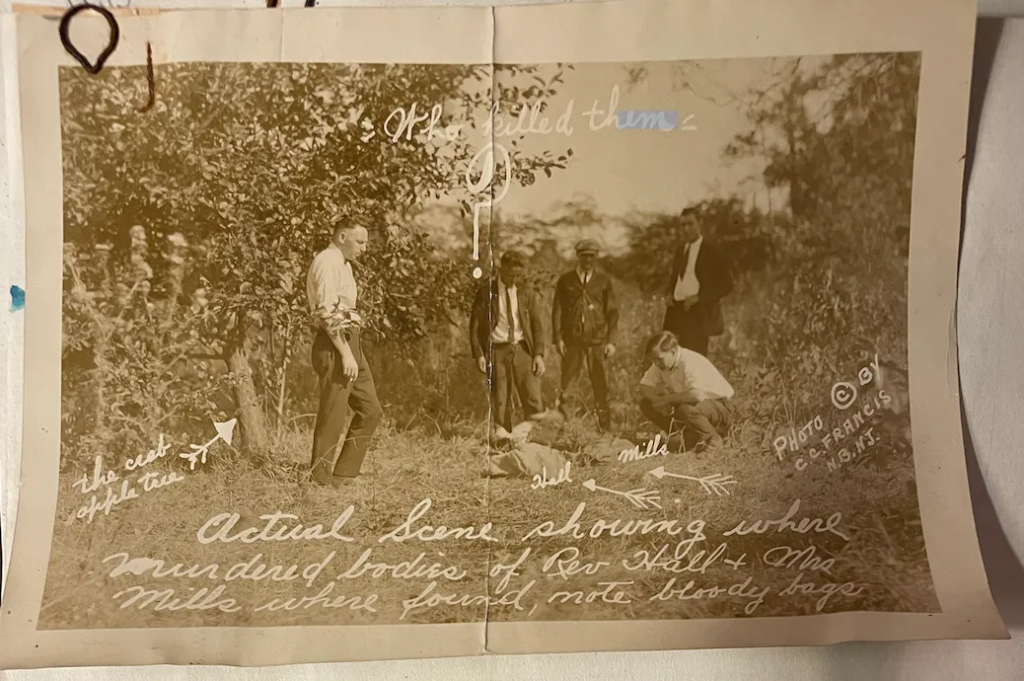

On the morning of September 16, 1922, Raymond Schneider and Pearl Bahmer walked along De Russ’s Lane, a farm road outside New Brunswick, New Jersey, searching for mushrooms. Beneath a crab apple tree, they saw a man and a woman lying side by side, their feet pointed toward the trunk. Neither moved.

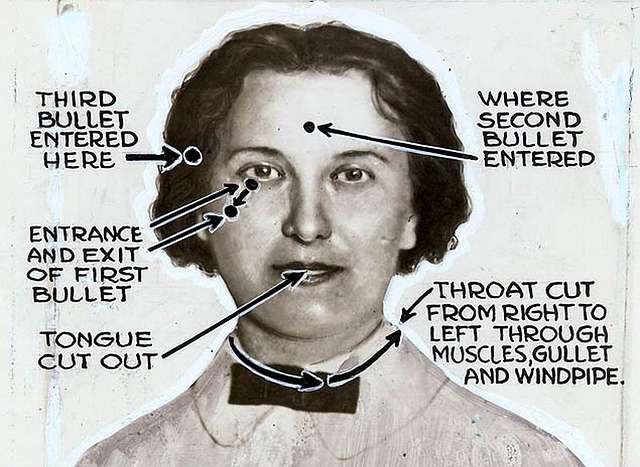

The woman’s face was covered with a shawl. The man’s face was covered by a hat. Schneider lifted the hat. The man had been shot once in the head and was dead. He then pulled back the shawl. The woman had been shot three times, under the right eye, in the right temple, and above the right ear. Her throat had been cut.

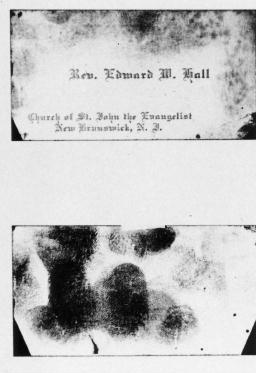

The bodies appeared deliberately placed. Their arms were positioned so they nearly touched. At the man’s feet lay a calling card. Torn love letters were scattered around the bodies. Police later pieced them together and confirmed they were letters exchanged between the two victims.

No gun was found at the scene.

The woman was wearing a red polka-dot dress and a wedding ring. A blue velvet hat lay beside her body. The man still had his wallet, with coins inside. There were no signs of robbery.

Authorities were notified shortly afterward, and officers arrived at the location.

Police from New Brunswick arrived first, believing the bodies were in Middlesex County. Within hours, it was discovered the site was actually in Somerset County, inside Franklin Township. Control of the scene shifted back and forth.

During the delay, the area was never sealed. Curious locals walked through the site, stepping near the bodies and handling items on the ground. At least one person picked up the calling card and passed it around. Footprints were ignored, and handprints were never secured.

By the time Somerset County officers took control, the ground had been trampled. Evidence had been moved, touched, or lost. No clear perimeter was established, and no early photographs documented the scene as it was first found.

Detective George Totten eventually ordered the bodies removed to the morgue. By then, the original condition of the scene could no longer be reconstructed.

The investigation began with critical evidence already compromised.

Edward Wheeler Hall was born on June 12, 1881, in Kings County, New York. He was raised in a deeply religious family with strong ties to the Episcopal Church. From an early age, he showed academic ability and a strong interest in theology.

After completing his education, Hall attended a theological seminary in New York City. He was known for clear speech, confidence, and strong command of scripture. These traits helped him rise quickly within the church.

Hall later became rector of St. John the Evangelist Episcopal Church in New Brunswick, New Jersey. He was popular with parishioners. His sermons were well attended, and he was active in church programs and local charities. Publicly, he was seen as disciplined, moral, and dependable.

In 1911, Hall married Frances Noel Stevens Hall, a wealthy woman from a prominent New Brunswick family. She was seven years older than him. The marriage elevated Hall’s social standing and financial security. To the public, the couple appeared stable and respectable.

Privately, rumors followed Hall. Some parishioners questioned his closeness with female members of the church. These concerns remained quiet—until his death placed his private life under scrutiny.

Eleanor Reinhardt Mills was born in 1888 in New Brunswick, New Jersey. She grew up in a working-class home and showed an early interest in music. Singing became a central part of her life.

In 1905, she married James Mills, who worked as the sexton at St. John the Evangelist Episcopal Church and as a janitor at a local school. The couple had two children: a daughter, Charlotte, born in 1906, and a son, Daniel, born in 1910.

Eleanor sang in the church choir and attended rehearsals regularly. She was known within the congregation and often interacted with church leadership. Her role placed her in frequent contact with Reverend Hall.

Her marriage was described by acquaintances as strained. The family struggled financially, and the relationship between Eleanor and her husband was reportedly unhappy. By 1922, she had discussed the possibility of divorce with at least one person.

To the community, Eleanor was a familiar and visible figure at church. After her death, attention quickly shifted from her public role to her private life, as investigators began examining her relationship with the rector.

By 1922, the relationship between Edward Wheeler Hall and Eleanor Reinhardt Mills was no longer limited to rumor. Investigators later confirmed that the two were engaged in an intimate relationship.

The pair exchanged love letters, several of which were found torn and scattered near their bodies on De Russ’s Lane. When reconstructed, the letters showed clear expressions of affection and emotional attachment between the two.

Parishioners had noticed the closeness. Hall and Mills were seen meeting privately, sometimes in secluded areas and sometimes inside the church itself. Their interactions drew quiet attention within the New Brunswick community, though no formal complaint was made.

Eleanor had spoken about divorce shortly before her death. On the night she disappeared, she attempted to reach the Hall household by telephone twice but did not get through.

On the evening of Thursday, September 14, 1922, witnesses later reported seeing Eleanor alone on De Russ’s Lane. Reverend Hall was also seen in the same area around 9:00 p.m. That night, neither returned home.

The affair, once whispered about, would soon become the central focus of a murder investigation.

Autopsies were performed by Dr. R. M. Long. He estimated that both victims had been dead for at least 36 hours before they were found. Each had been killed by gunfire from a .32-caliber weapon.

Reverend Hall had been shot once in the head. Eleanor Mills had been shot three times and had her throat cut. Dr. Long could not say for certain whether the killings happened at the exact spot where the bodies were found.

Hall’s gold watch was missing, but his wallet was still in his pocket and contained coins. Eleanor’s jewelry had not been taken. Based on this, police ruled out robbery as a motive early in the investigation.

Years later, a major issue emerged. Eleanor Mills’s original autopsy report had been lost. Her body was exhumed, and a second autopsy was conducted. During this examination, it was discovered that her tongue had been cut out—a detail not documented in the first report.

The missing report, the delayed discovery, and the damaged crime scene added new questions but provided few clear answers.

Police first looked at James Mills, Eleanor’s husband. He had a clear personal motive and was closely connected to both victims. Mills cooperated with investigators and showed visible distress. He said that on the night of September 14, he was home working. His children and a neighbor supported his account. Police found no evidence placing him on De Russ’s Lane, and he was eventually cleared.

Attention then turned to Frances Stevens Hall, the rector’s wife. Investigators questioned whether she knew about the affair and feared her husband was planning to leave her. Preserving her social standing and family name became a possible motive.

Frances Hall said she was at home on the night of the murders. Her maid, Louise Geist, supported this claim. Police were not fully satisfied and continued to examine her movements and behavior.

Her brothers, Henry Stevens and William Stevens, also became suspects. Henry was known as withdrawn and unpredictable. William had intellectual limitations. Witnesses later claimed to have seen one or more of them near the area around the time of the murders.

Despite suspicion, police lacked physical evidence linking any of them directly to the crime scene. No arrests were made, and the investigation stalled as public attention continued to grow.

In late 1922, a woman named Jane Gibson came forward with a dramatic account. She lived near De Russ’s Lane and raised pigs, which led the press to nickname her the “Pig Woman.”

Gibson told police she was awakened on the night of September 14, 1922, by loud voices outside. She said she went out and saw four figures in the dark. One, she claimed, was a woman in a long coat whom she later identified as Frances Stevens Hall.

According to Gibson, she heard an argument. She said a man was shot and fell to the ground. She then heard a woman shout “Don’t,” followed by more gunshots. She said she saw a woman fall.

Her story drew heavy attention from police and newspapers. But her statements changed over time. Details shifted. Dates and positions did not always match known facts. Investigators struggled to confirm her account.

Despite the doubts, Gibson’s story kept suspicion focused on Frances Hall and her brothers. It also pushed the case deeper into public spectacle, even as solid evidence remained scarce.

By late 1922, the investigation had slowed. No arrests were made, and police said the evidence was not strong enough to move forward. Public interest remained high, but the case began to fade.

That changed in 1926.

A man named Arthur Bell Real came forward during a divorce from his wife, Louise Geist, who had once worked as Frances Hall’s maid. Real claimed his wife had told him that Frances Hall knew her husband planned to leave her and run away with Eleanor Mills.

According to Real, Frances Hall and her brothers confronted the couple on De Russ’s Lane on the night of September 14, 1922. He alleged that the brothers killed both victims to protect the family name and that Louise Geist had been paid to stay silent.

Louise Geist denied the claims. She called them false and said her husband was lying. Still, the story spread quickly in the press and renewed public pressure.

The attention reached A. Harry Moore, who ordered a second investigation. Prosecutors reopened the case, reviewed old evidence, and interviewed witnesses again.

By the end of 1926, authorities announced they believed there was enough evidence to proceed. Frances Stevens Hall and her brothers, Henry and William Stevens, were formally charged with murder.

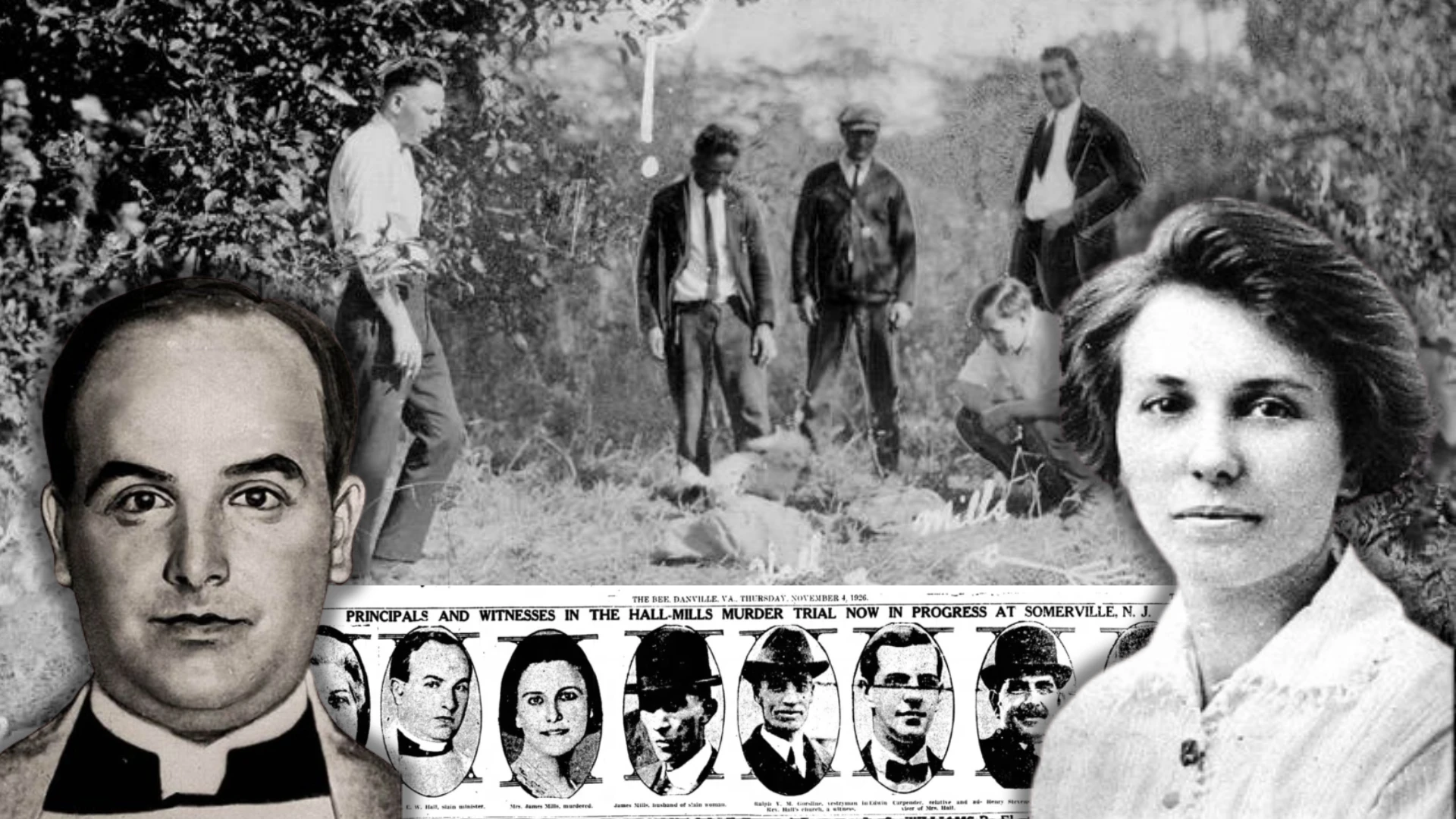

The trial began on November 3, 1926, in Somerville, Somerset County. Frances Stevens Hall, along with her brothers Henry and William Stevens, pleaded not guilty.

The defense was led by Robert H. McCarter, one of the state’s most prominent lawyers. He focused on the lack of direct evidence and the damage done to the crime scene in 1922.

Prosecutors relied heavily on witness testimony. Jane Gibson was brought into court on a hospital bed, seriously ill. She repeated her account of seeing figures on De Russ’s Lane and hearing gunshots. Under questioning, her story showed inconsistencies. The defense challenged her memory, timing, and reliability.

Other witnesses testified they had seen Henry Stevens near the area around the time of the murders. The defense noted that these statements surfaced months later and could not be verified.

A fingerprint belonging to William Stevens was found on the calling card placed near Hall’s body. The defense argued the card had been handled by many people after the scene was overrun by onlookers, making the print meaningless.

No weapon was ever produced. No witness placed any defendant directly committing the killings. The prosecution could not show who fired the shots or who cut Eleanor Mills’s throat.

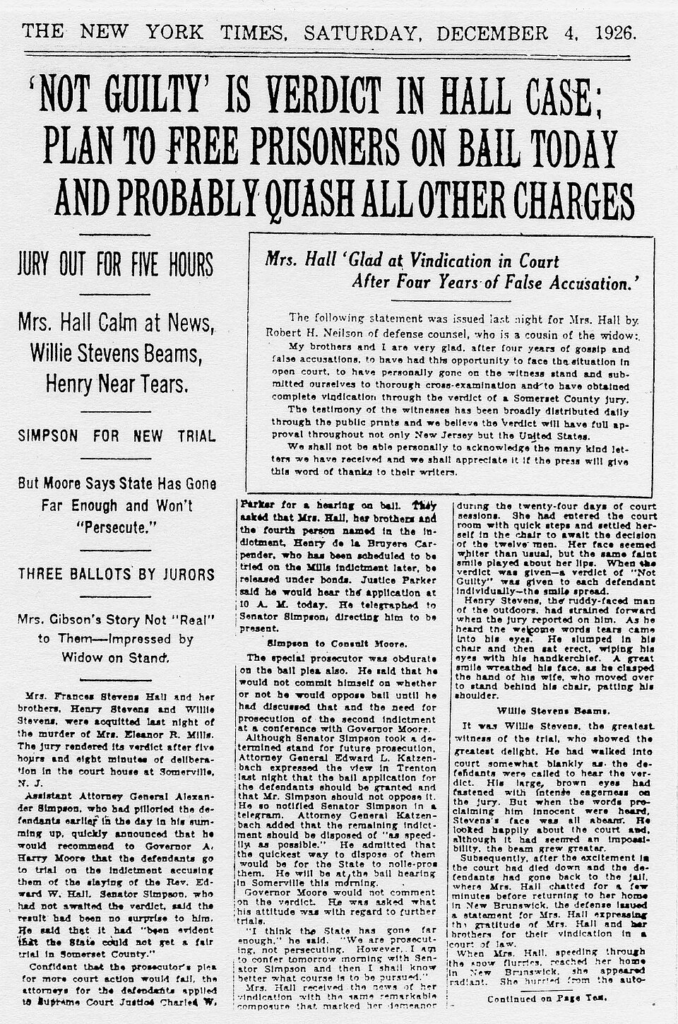

On December 3, 1926, after weeks of testimony, the jury returned its verdict. All three defendants were found not guilty.

After the verdict, Frances Stevens Hall returned to New Brunswick. She continued living in the same house she had shared with her husband. She did not remarry and rarely spoke about the case in public. She died in 1942.

Her brothers, Henry and William Stevens, also returned to private life. Neither was ever charged again in connection with the murders.

The acquittal did not end public interest. Many people believed the defendants had escaped justice. Others pointed to the lack of solid evidence and the ruined crime scene as the real reason the case failed.

No further arrests were made. The murders of Edward Wheeler Hall and Eleanor Reinhardt Mills remained officially unsolved.

The case continued to be discussed in newspapers, books, and later radio programs, often cited as an example of how early mistakes can permanently damage a criminal investigation.

After the trial, several theories remained. The most common held that the murders were driven by jealousy and family loyalty, with Frances Stevens Hall acting with or through her brothers to stop her husband from leaving and to protect the family’s reputation. The jury’s verdict did not confirm this, but public belief persisted.

A robbery theory was raised early but quickly weakened. Hall’s watch was missing, but his wallet and Eleanor Mills’s jewelry were untouched. The posed bodies and love letters did not fit a robbery.

Others suggested a crime of passion by a third party. No evidence ever supported this. Some pointed to a broader cover-up, arguing that wealth, status, and political pressure shaped the investigation. The early loss of evidence and conflicting testimony fueled that belief.

Modern forensic methods offer little help. The crime scene was contaminated. Key evidence was lost. The weapon was never found. The case cannot be retested in any meaningful way.

More than a century later, no one has been held responsible. The murders of Edward Wheeler Hall and Eleanor Reinhardt Mills remain unsolved, not because there were no suspects, but because the truth was never proven.