John “J.R.” Robinson, a fleshy man of 41 with wavy brown hair and a winning smile, left his four-acre estate in the horsey exurbs southwest of Kansas City, Missouri, and drove to an apartment in the city where he kept the woman he called his mistress. The trip from the rolling Kansas prairie across the Missouri border to the gritty, urban precincts of Troost Avenue took barely half an hour. It was still early on this Saturday morning in late May of 1985.

Robinson let himself into the brick apartment building—he had his own keys—and then into the apartment itself, a two-bedroom unit on the third floor. The woman in residence, Theresa Williams, 21, had been asleep but bolted awake when Robinson barged into her bedroom.

J.R. grabbed Theresa by the hair, pulled her over his knee, and started spanking her.

“You’ve been a real bad girl,” he snarled. “You need to learn a lesson.”

Theresa, momentarily speechless, started screaming. J.R. threw her to the floor and drew a revolver from a shoulder holster.

“If you don’t shut up, I’ll blow your brains out.” He put the gun to her head and pulled the trigger. There was a loud click. The chamber was empty.

Cowering and crying softly now, Theresa stiffened as J.R. slid the gun down her torso and stuck the barrel into her vagina.

“I’ll bet you’ve never had a blowout,” he said.

“Don’t do that!” she pleaded.

J.R. withdrew the gun from Theresa’s body, holstered it, and left the apartment as suddenly as he had entered. The terrified woman, her sobs slowly ebbing, did not summon help. She felt helpless. One did not cross J.R. Robinson.

J.R. drove from Troost Avenue back across the state line to his Kansas home, where he arrived in time to attend his teenage son’s regular Saturday soccer game. To all appearances, J.R. Robinson was a doting father and husband. A skilled handyman, he had built a soccer goal in the family’s spacious yard so his son could practice at home. He attended his daughter’s flute recitals and band concerts, and refereed school volleyball games.

His neighbors knew J.R. as a successful businessman and entrepreneur, always talking of new ventures. He was a neighborhood activist, an officer of the residents’ association, and chairman of its rules committee. He was also a founding elder of the nearby Presbyterian Church.

Neither his neighbors nor his children knew that J.R. Robinson led a second life—secret and sordid—dating back nearly two decades. (How much his wife knew was unclear, even years later.) J.R. was a swindler, an embezzler, and a forger. He was a sexual predator, a deviant, and a pimp. And in the mid-80s in Kansas he was becoming something much more sinister—a murderer of women.

Indeed, J.R. Robinson is rare in the annals of American crime: a genial con man and a homicidal monster all in one. Unlike Ted Bundy or John Wayne Gacy, who chose their victims impulsively and killed them with dispatch, Robinson developed relationships with his. Using the Internet and his own considerable charm, he lured them to Kansas with offers of employment and sadomasochistic sex. He exploited them financially, enticing them into giving him their life savings and retirement accounts, cashing their disability checks, and, in one case, selling a victim’s baby to his brother and sister-in-law. Then, prosecutors allege, he beat at least five women to death with a blunt object, most likely a large hammer.

“I’ve dealt with a wide variety of characters, but never anyone like Robinson,” says Stephen Haymes, 49, who has been a probation officer for 26 years and who saw through Robinson far sooner than anyone else in law enforcement. “He’s just chilling. There are so many sides to him. There is the con man after money. There is the murderer. There is the sexual deviant. There is the cover-up artist—the lies, endless lies.”

The real Kansas belies its image. I know because I grew up there, as did my parents and grandparents. Kansas isn’t nearly so flat as it appears from 35,000 feet; the Flint Hills of eastern Kansas are craggy and stark. Kansas isn’t bland; Come Back, Little Sheba and Picnic, by William Inge of Independence, Kansas (where my mother was born and her uncle was district attorney), reveal as much elemental human strife in small-town Kansas as in the urban East of Eugene O’Neill and the South of Tennessee Williams.

Kansas isn’t peaceful either; murder and mayhem stain its history and stain it today. The cattle centers of Dodge City and Abilene (my father’s hometown) were as violent as any other towns west of the Mississippi in the 19th century. In 1892 four members of the Dalton Gang were shot to pieces in Coffeyville, after trying to rob two banks in the same day. Staggering quantities of blood were spilled along the Missouri border in the 1850s when Missouri, a slave state, tried to impose its ways on Kansas. The anti-slavery zealot John Brown and his allies clashed so violently with pro-slavery forces that the region became known all the way to Washington, D.C., as “bleeding Kansas.” In the 20th century too, Kansas saw more than its share of violence. The Ma Barker and Pretty Boy Floyd gangs crisscrossed the state in the 1930s. When Perry Smith and Richard Hickock drove to western Kansas in 1959 and slaughtered the Clutter family, chronicled in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, they left from the town of Olathe (pronounced “Oh-*lay-*thuh”), Hickock’s hometown, just a few minutes from where J.R. Robinson lived two decades later.

Still, Kansas retains a know-your-neighbor, help-your-neighbor quality of life that makes it seem different—even from adjacent Missouri—and gives the atrocities of John Robinson a special horror. This story presents the case against Robinson as reflected in a three-month Vanity Fair investigation, which includes detailed evidence gathered by Kansas and Missouri prosecutors and law-enforcement officers and set forth in court.

John Edward Robinson was born not in Kansas but in Cicero, Illinois, a blue-collar, Mafia-tinged enclave on the west edge of Chicago, in 1943. He was the middle child of five. His father, Henry, was a machinist for Western Electric and a binge drinker. His mother, Alberta, was the family disciplinarian and turned young John into a teenage star—at least briefly. When he was 13, in the fall of 1957, he enrolled in the Quigley Preparatory Seminary in the heart of downtown Chicago, a five-year academy for Catholic boys. That same fall he made the rank of Eagle Scout and flew to London to lead a group of 120 Boy Scouts onto the stage of the Palladium theater to appear in a command performance of a Scout variety show before Queen Elizabeth II. According to a Chicago Tribune article at the time, unearthed much later by The Kansas City Star, Robinson was selected for the honor “because of his scholastic ability, scouting experience, and poise. . . . He also has an engaging smile.” Backstage he met Judy Garland. “We Americans gotta stick together,” young Robinson told her.

Robinson’s smile and choirboy mien were on display in that year’s Quigley yearbook. He did not appear in subsequent yearbooks, however, and seemed to disappear for a time, according to investigators who have probed his background. Robinson attended a Cicero junior college in 1961 and studied medical X-ray technology. He did not graduate, and next surfaced three years later in Kansas City, Missouri. He was 21 and had married a woman named Nancy Jo Lynch.

It wasn’t long before John Robinson ran afoul of the law. He was employed as a laboratory technician and office manager by a Kansas City physician, Wallace Graham, who had been President Harry Truman’s personal doctor. In June 1967, Graham reported to the Kansas City police that Robinson had embezzled about $33,000 from him by manipulating checks and deposits. Robinson was prosecuted and found guilty by a jury of “stealing by means of deceit.” He avoided jail, but was placed on probation for three years.

While on probation, Robinson got a job as a manager of a television-rental company. He stole merchandise and was fired but not prosecuted. In 1969 he went to work as a systems analyst for the Mobil Oil Corporation, which wasn’t aware that he was on probation.

In choosing not to inform Mobil of Robinson’s background, his probation officer said in a memorandum to the Missouri Board of Probation and Parole that Robinson “does not appear to be an individual who is basically inclined towards criminal activities and is motivated towards achieving middle class values.” Another officer stated on August 13, 1970, that Robinson was “responding extremely well to probation supervision” and she was “encouraging [him] to advance as far as possible with Mobil Oil.”

Precisely two weeks later Mobil Oil discovered that Robinson had stolen 6,200 U.S. postage stamps from the company. He was fired, reported to the police, and charged with theft. The following month, Robinson and his wife moved back to his home city of Chicago, where he got a job with a company called Illinois R. B. Jones. Within a month he was stealing again; he embezzled $5,500 over six months before he was caught and fired. Robinson’s father gave him the money to make restitution, so Illinois authorities dismissed criminal charges.

Robinson and his wife moved back to the Kansas City area, where he was arrested for violating the terms of his probation and thrown in jail “to provide a strong motivation for a complete reversal in his behavior,” wrote Gordon Morris, a Missouri probation officer. Robinson was released after only a few weeks and his probation was extended five years—to 1976.

Probation authorities still believed that “prognosis in this case is good,” as they stated in an April 1973 report. They did not know that Robinson was already stealing again, this time from his next-door neighbor Evalee McKnight, a retired school-teacher who gave Robinson $30,000 to invest, according to police records I reviewed in Kansas. She never saw the money again.

Oblivious to all of this, Missouri probation authorities discharged Robinson from probation in 1974, two years early.

Around this time Robinson started a company he called Professional Service Association Inc. (P.S.A.), purportedly to provide financial and budget consultation to physicians in the Kansas City area. Two groups of doctors at the University of Kansas medical school hired him to manage their financial affairs. The doctor who interviewed Robinson later told The Kansas City Star, “He made a very good impression: well-dressed, nice-looking . . . seemed to know a lot, very glib, good speaker.” The doctors dismissed Robinson after only a few months, however, because of irregularities in his handling of their finances.

But that didn’t stop Robinson, who was sending letters to potential investors in P.S.A., portraying a growing, healthy company. One letter suggested that Marion Laboratories, founded by Ewing M. Kauffman, then owner of the Kansas City Royals baseball team, was negotiating to purchase P.S.A. It wasn’t.

Federal authorities got wind of the scheme, and a U.S. grand jury indicted John Robinson on four counts of securities and mail fraud. In June 1976 a federal judge fined him $2,500 and placed him on three years’ probation. It was his third such sentence in six years. He had served only a few weeks in jail. And authorities didn’t even know of all the crimes committed by Robinson, a pathological thief dodging easily through the system.

In 1977, John Robinson, now 34, moved his growing family—he and Nancy by this time had four children—a few miles across the state line into Kansas. They bought a nine-room house on four acres in a neighborhood called Pleasant Valley Farms, in the southern reaches of Johnson County, which stretched south and west into Kansas from the Missouri border. It was one of the richest counties in the United States, 480 square miles of sleek suburban affluence—some of the towns had Shawnee names, such as Lenexa (for the wife of an Indian chief), and the county seat, Olathe (“beautiful”). The people of Johnson County felt a bit superior to their Missouri neighbors, and once you crossed into Kansas there was a different feeling. The light seemed brighter, the landscape less dingy. The Kansans were richer, smarter, nicer, gentler.

Pleasant Valley Farms, with its vistas across rolling hills, stands of elm and maple trees, bridle path, and lake stocked with fish, felt rural and remote, even though it was less than an hour’s drive northeast to downtown Kansas City. The Robinsons’ new home was a modern asymmetrical structure of wood, brick, and stone on four levels with two big stone fireplaces. It nestled in the middle of the property, with a horse stable and corral at the back, against a tree line along the ridge of a low hill. The Oregon and Santa Fe Trails, along which thousands of settlers had made their way west in the 19th century, coincided in eastern Kansas, and their route traced the back of the Robinsons’ property.

John Robinson had a new career to go with his new home—hydroponics, a method of growing vegetables in a controlled nutrient-rich indoor environment. He started a company, Hydro-Gro Inc., and produced a 64-page booklet. Fun with Home Hobby Hydroponics: “We hope that as you read this book you will form an acquaintance with John Robinson as a sensitive and stimulating human being,” the introduction said, portraying Robinson as “one of the nation’s pioneers in indoor home hydroponics” and a “sought after lecturer, consultant and author.”

Whatever they thought of hydroponics, Robinson’s new neighbors found him intelligent and energetic, conversing knowledgeably about international finance and other business matters at local picnics. In addition to helping run the neighborhood association, he was a visible neighbor, working in his yard a lot, installing a rail fence and a pond. His children—John junior, who was 14 years old; Kimberly, 12; and twins Christopher and Christine (“Chris” and “Chrissie”), who were 8—were well behaved and popular. John junior helped his father with work around the property. Chris and Chrissie took care of the dogs and cats of their neighbors Margaret and Jim Adams when the Adamses traveled. Margaret Adams enjoyed having Chrissie come over and pick strawberries in the garden.

John Robinson’s neighborhood activism extended to civic activism, or so it appeared. GROUP FOR DISABLED HONORS AREA MAN, headlined The Kansas City Times on December 8, 1977. The article reported that John Robinson, president of Hydro-Gro Inc., had been named “Man of the Year” for his work with the handicapped. He headed the board of a “sheltered workshop,” which employed disabled people, the newspaper said. The award, a “proclamation” signed by the mayor of Kansas City, turned out to be one of the more bizarre episodes in Robinson’s checkered career. Two weeks after the newspaper report, it was revealed that Robinson had orchestrated the award himself through a complex sequence of fake letters of recommendation he had sent to city hall. The Kansas City Star, then the afternoon counterpart of the Times, revealed the ruse in a story headlined MAN-OF-THE-YEAR PLOY BACKFIRES ON “HONOREE.”

As his neighbors in Pleasant Valley Farms got to know John Robinson better, they noticed that he could be prickly and even mean when upset. Margaret Adams, an avid gardener, recalls that she once asked him to demonstrate his hydroponics system. He gladly complied and was pleasant until she told him that she felt his price for the system was too high. “You’ve wasted my time—you’re small potatoes,” he snapped, abruptly terminating the encounter.

Robinson nearly came to blows with another neighbor over a misbehaving dog. And he became disenchanted with the neighborhood association, accusing it in a formal letter of being “invalid” when, in his opinion, it failed to enforce some of its rules. “He was cocky and arrogant,” another neighbor told me. “You needed to walk on eggs around him.”

Robinson liked to control his surroundings. Neighbors occasionally heard him yelling at his wife and children, ordering them about like a drill sergeant. The children followed his orders and seemed to thrive on the discipline, becoming model citizens who adored their father. Nancy, however, began divorce proceedings, and the marriage survived only after counseling.

In 1980, Robinson, while continuing to run Hydro-Gro, took a job as the director of personnel at a Kansas City subsidiary of Borden Inc., the global food company. Borden did not check Robinson’s background. Within a few months the company caught Robinson stealing—again by manipulating checks and bank deposits to divert funds to his financial company, P.S.A. The losses totaled more than $40,000, part of which Robinson spent on an Olathe apartment where he conducted sexual liaisons with two women who worked for Borden, police records and internal Borden documents show. “John kind of swept me off my feet,” one of the women told a police detective in a formal interrogation. “He treated me like a queen. . . . He always had money to take me to nice restaurants and hotels.”

Fully cognizant of Robinson’s criminal record, the Missouri authorities still coddled him. He faced a maximum sentence of seven years, but spent only two months in prison and was again placed on probation, this time for five years.

The Borden scandal caused hardly a ripple in Robinson’s neighborhood, where he managed to bluff it through as a misunderstanding over a business matter. He went on running Hydro-Gro and set up another company, Equi-Plus, which purported to offer management-consulting services. One of Equi-Plus’s first customers in the early 80s was a company called Back Care Systems, which ran seminars for corporations on treatment of back pain. Back Care hired Equi-Plus to develop a marketing plan. When the company began getting invoices from Equi-Plus that appeared to be inflated or in some cases bogus, it reported Robinson to the Johnson County district attorney’s office, which began a criminal investigation. Robinson’s lawyer advised him to obtain sworn affidavits attesting to the legitimacy of the invoices. Robinson did so. He faked the affidavits.

Undaunted by the investigation of Equi-Plus, John Robinson created another company, Equi-II, as an umbrella corporation to absorb Equi-Plus and engage in a variety of business and “philanthropic” ventures. He had used his previous companies to perpetrate financial fraud and theft, but his new company would serve an additional, more sinister purpose: luring young women to their deaths.

One of the people he hired to work for him, in 1984, was Paula Godfrey, a pretty, dark-haired young woman who had graduated from high school in Olathe the previous year. Robinson told Godfrey, an honor student and accomplished figure skater, that he would enroll her in a training course in Texas and pay all her expenses. On the day of her scheduled departure, Robinson picked her up at her parents’ home in Overland Park, a Johnson County suburb, to go to the airport. After not hearing from her for several days, the Godfreys reported to the police that their daughter was missing. The police checked with Robinson, who disclaimed any knowledge of her whereabouts. Shortly thereafter, the police received a letter purportedly signed by Paula Godfrey stating that she was “O.K.,” and that she did not want to see her family. Having no contrary evidence, the police suspended their investigation. It was a decision they would come to regret. Many people now believe that Paula Godfrey was Robinson’s first murder victim.

Robinson soon offered help to other young women. In December 1984 he presented himself to social workers at the Truman Medical Center, the leading public hospital in Kansas City, and to an organization called Birthright, which counseled unwed, pregnant young women and aided them after delivery of their babies. Robinson told both groups that he and several other businessmen in Olathe and Overland Park had started an organization called Kansas City Outreach. It provided housing for young unwed mothers and their babies, Robinson said, as well as job training and baby-sitting. Robinson invited Truman Medical Center and Birthright to submit candidates for the services and said the program would likely receive funding from Xerox, IBM, and other major corporations.

In early January 1985, Truman Medical Center put Robinson in touch with a 19-year-old woman named Lisa Stasi, who had just given birth to a daughter, Tiffany. Lisa and her husband, Carl, had separated. Robinson indicated that he would house Lisa and Tiffany at an apartment he had rented on Troost Avenue, an area of small businesses and apartments in south Kansas City. When Robinson spoke to Stasi directly, he told her that his name was John Osborne and that he could help her get a high-school equivalency diploma and job training not only in Kansas City but in Chicago and Denver as well. Instead of putting her up at the Troost Avenue apartment, Robinson installed Lisa and Tiffany at a Rodeway Inn in Overland Park.

On January 8, Robinson told Stasi that he had arranged for her and the baby to travel to Chicago in a day or two. In preparation, Robinson had Stasi sign four blank sheets of stationery and give him the addresses of her relatives. He would notify them of her whereabouts, he said, because she would be too busy in Chicago to write letters.

Stasi spent several hours that day and the next with Kansas City relatives who tried to dissuade her from going to Chicago. How well did she really know John Osborne? they asked. “He is a gentleman,” she replied. On the afternoon of January 9, Robinson drove from Overland Park through a heavy snowstorm to pick up Stasi at the home of her sister-in-law, Kathy Klinginsmith, in Kansas City. Angry that she had left the Rodeway Inn, he insisted that they leave immediately. Stasi, carrying Tiffany, accompanied Robinson, whom she still knew as John Osborne, to his car, leaving most of her belongings and her own car at her sister-in-law’s. As Klinginsmith watched the man take Lisa off into the snow, she would later say in court, “I was afraid of him. I knew deep down that was the last time I would see Lisa.”

The next morning Klinginsmith telephoned the Rodeway Inn where Stasi had been staying. A clerk said that she had checked out and her bill had been settled by a John Robinson, not John Osborne, with a corporate credit card in the name of Equi-II. Klinginsmith’s fear deepened into panic.

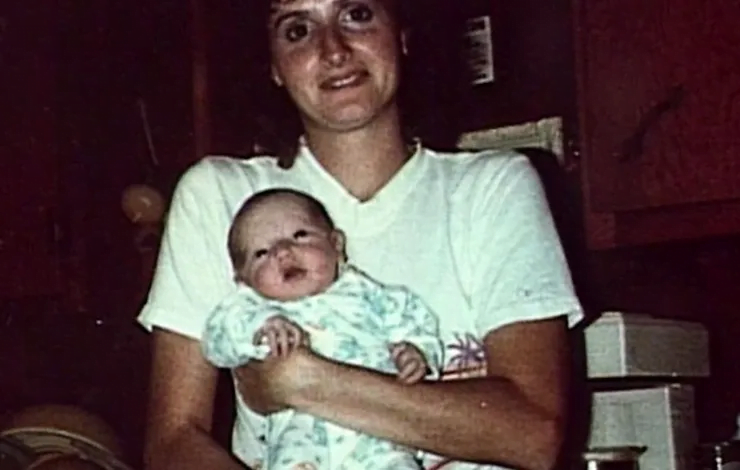

There was a festive party that evening at the Robinsons’ home in Pleasant Valley Farms. John Robinson’s brother and sister-in-law, Don and Helen Robinson, had been trying for years to adopt a baby. John had told them that he had connections in Kansas City who might help. That morning they had flown from Chicago to Kansas City, where John met them at the airport and took them to the offices of Equi-II in Overland Park. Don and Helen signed what looked like official adoption papers and paid John $5,500 in cash. He then drove them to his home, where Nancy awaited them with a healthy female infant in her arms. John had brought the baby home unannounced the previous evening, Nancy recalled later in court. A photograph of the occasion shows the happy extended family celebrating in John and Nancy’s living room. At the center of the picture, looking every inch a godfather, is John Robinson with the baby on his lap.

John confided to Don and Helen that the baby had become available for adoption when her mother had committed suicide. The new parents named the baby Heather and the next day, January 11, flew back to Chicago, not knowing that Heather already had a name, Tiffany Stasi.

That same day Kathy Klinginsmith’s husband, David, appeared at the offices of Equi-II in Overland Park and confronted Robinson on the whereabouts of Lisa Stasi and Tiffany. Robinson physically ejected David Klinginsmith from the office. Kathy, meanwhile, drove to the Overland Park Police Department and reported her sister-in-law and the baby missing.

Robinson’s approach to Birthright had been more problematic, because Ann Smith, the Birthright employee to whom Robinson had first spoken, grew suspicious. Robinson had told her that Kansas City Outreach was supported by the Presbyterian Church he had helped found near his home in Pleasant Valley Farms. He also told her that his program’s supporters included an Olathe bank on whose board of directors he sat.

Smith called both the church and the bank. The church acknowledged that Robinson was a member, but said it had no connection to any program to help unwed mothers. The bank said Robinson was not on its board; it had never heard of him.

Smith made more inquiries, which eventually, on December 18, 1984, led her to a district supervisor of the Missouri Board of Probation and Parole, a slim, mustachioed, soft-spoken man named Stephen Haymes, then 32 years old. Missouri-born-and-bred, he had majored in sociology and criminal justice in college. When poor eyesight had barred him from many jobs in law enforcement, he had settled on a career as a probation officer.

Haymes, taking Ann Smith’s call in Missouri, had never heard of Robinson, who was supervised by a Kansas probation officer in Olathe. He pulled Robinson’s file and perused his lengthy criminal record. After checking with his Kansas counterpart, who reported no problems with Robinson, Haymes sent a letter to Robinson ordering him to report to the Missouri probation office on January 17, 1985. Robinson did not show up. Haymes sent him another letter, registered this time, ordering an appearance on January 24.

Haymes also telephoned a contact in the Kansas City field office of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, a supervisor with whom he had worked in the past, to ask if the F.B.I. was investigating Robinson or was aware of any “baby selling rings” operating in the Kansas City area. The answer to both questions was no, though the supervisor said the bureau was “aware” of John Robinson.

Robinson arrived at Haymes’s office promptly at one P.M. on January 24. At five feet nine and 200 pounds, Robinson reminded Haymes of the Pillsbury dough boy, though he was more nattily dressed. He was friendly and deferential and had an answer for just about everything. Yes, he had met with Birthright, as part of an effort by several of his “business associates” to “help the community.” No, he had not told Birthright that the Presbyterian Church was behind the effort. The Birthright people had misunderstood; they had asked him what church he attended and he had told them. Robinson volunteered that he also had met with social workers from the Truman Medical Center and that they had placed two young women in an apartment he had rented on Troost Avenue. Haymes was welcome to visit the apartment and speak with the residents, Robinson said.

Robinson’s mention of Truman Medical Center was the first Haymes had heard that Robinson’s efforts had gone beyond Birthright, according to contemporaneous notes Haymes kept and I reviewed. In subsequent days, the probation officer spoke to the Truman Medical social workers and learned that their clients in the Troost Avenue apartment were doing well. However, another young woman, Lisa Stasi, whom Truman had referred to Robinson, seemed to have disappeared, and the Overland Park police were looking for her. Truman Medical was concerned.

Haymes called an Overland Park detective, who said they had found no evidence of wrongdoing in the Stasi case and weren’t pursuing it. The detective mentioned, however, that a second young woman who had worked for Robinson, Paula Godfrey, had been reported missing a few months earlier. The detective recounted the letter the police had received, purportedly from Godfrey, saying she was O.K. and didn’t want to see her family. The police weren’t pursuing that case, either.

Steve Haymes was skeptical. From Stasi’s relatives he learned that Robinson had her sign four blank sheets of stationery. Two letters arriving shortly after she disappeared looked suspicious. They didn’t sound like Lisa. And they were typed. Lisa didn’t know how to type.

Haymes asked Robinson where Stasi was. Robinson claimed she had run off to Colorado with a guy named “Bill.”

Haymes was now deeply concerned. It was conceivable that Robinson, already a pathological con man, had metastasized into a killer of vulnerable young women. Haymes called the F.B.I. supervisor again. “You need to take a look at this,” Haymes said. “We’ve got two women and a baby missing. We’ve got Robinson crossing state lines.” The supervisor assigned two agents to begin an inquiry.

Over the next few weeks, Special Agent Thomas Lavin, a veteran of the F.B.I., and his young partner, Special Agent Jeffrey Dancer, who had been an agent less than a year, began pooling their efforts with the now relentless Haymes. They discovered that Robinson was involved in an astonishing variety of ongoing criminal activities in the Kansas City underworld. Robinson and a fellow ex-convict, Irvin “Irv” Blattner, were under investigation by the U.S. Secret Service for forging the signature on and cashing a government check. Haymes and the F.B.I. learned as well of the investigation in Johnson County, Kansas, where the district attorney was building a case that Robinson’s company Equi-II had defrauded Back Care Systems.

It was around this time that Robinson developed a strong taste for sadomasochistic sex—generally defined as sexual activity between two people who agree that one will be dominant and the other submissive in seeking enhanced sexual pleasure through bondage and the infliction of pain through such means as spanking and whipping of the submissive by the dominant.

Sadomasochistic sex, or S&M, is also known by the abbreviation BDSM, for “bondage discipline sadomasochism,” or simply D&S, “dominance and submission.” Some 5 to 10 percent of American adults regularly engage in some form of D&S, according to Gloria and William Brame and Jon Jacobs, the authors of the 1993 book Different Loving: The World of Sexual Dominance & Submission.

J.R. Robinson not only engaged in BDSM himself, he saw it as a means to make money. He apparently was organizing a ring of prostitutes for customers interested in S&M, and using a male stripper, nicknamed M&M, to find women for him. In this circle of people, Robinson was known as “J.R.”

None of the investigative trails led to Lisa Stasi and her baby, or to Paula Godfrey. Still, it was clear to Haymes and the F.B.I. agents that Robinson was up to no good on several fronts. Haymes ordered Robinson in for another visit.

“Why is everyone making such a big deal when I’m only trying to help people?” Robinson complained, according to Haymes’s notes. “By the way,” he told Haymes, “Lisa Stasi has been found. She’s okay. Tiffany, the baby, everybody’s okay.”

Robinson claimed he had heard from a local woman for whom Stasi recently had baby-sat. She and Tiffany definitely were in the Kansas City area. That story collapsed, however, when F.B.I. agent Lavin and an Overland Park detective spoke to the woman in question. After rigorous questioning, she admitted that the story of Stasi baby-sitting for her was false; Robinson had asked her to tell the lie if the police asked. Her incentive to cooperate: she owed J.R. money, and he had photographed her nude as a prospective prostitute.

The F.B.I. decided to deploy a female agent to contact Robinson and pose as a prostitute looking for work. Wired to secretly record their conversation, the agent met Robinson for lunch in an Overland Park restaurant. He told her that his clients were mainly lawyers, doctors, and judges, and that she could earn $2,000 to $3,000 a weekend traveling to Denver or Dallas to service them, or $ 1,000 a night in the Kansas City area. As an S&M practitioner, she would have to undergo pain such as having her nipples manipulated with pliers, Robinson said. After hearing the recording of the conversation, the F.B.I. decided against proceeding with the undercover effort for the time being out of fear for the agent’s safety.

Irv Blattner, however, agreed to help the authorities make a case against Robinson in exchange for lenient treatment in the government-check-forgery investigation. The F.B.I. advised Truman Medical Center to remove its two young women from Robinson’s Troost Avenue apartment, but to give Robinson a plausible excuse.

One of the women whom the male stripper M&M had introduced to Robinson as a candidate for prostitution was Theresa Williams, an attractive 21-year-old itinerant from Boise, Idaho, who had been working odd jobs around Kansas City and looking for the main chance. Robinson took her to an Overland Park hotel room where he photographed her nude and offered her a position as his “mistress,” a job that would involve sexual services not only for him but for others as well. He would put her up in an apartment and pay all her expenses, plus prostitution fees. He would supply her with marijuana and amphetamines. Williams took the job.

On the night of April 30, 1985, J.R. gave Williams $1,200 in cash, outfitted her in a fancy, alluring dress, and told her to wait in a park across the street from the Troost Avenue apartment. A limousine picked her up. The driver blindfolded her and took her to a mansion somewhere in the Kansas City area. She was turned over to a distinguished-looking, 60-ish gray-haired man who was called “the judge.” He escorted her to the basement, which was outfitted as a “dungeon” for sadomasochistic sex, or “brutality and other unnatural sex acts,” as Williams later put it. The man had her disrobe, and then began stretching her on a medieval rack. She screamed in panic and demanded that he allow her to leave. She was blindfolded again and returned to the Troost Avenue apartment, where, a few days later, she was forced to return the $1,200 to an angry John Robinson.

She incurred J.R.’s wrath further when he found out that she had been entertaining a boyfriend—not one of Robinson’s customers—at the apartment. It was behavior such as this that prompted his early-morning visit on a Saturday in late May when he allegedly assaulted her with his gun.

They made up, however, and J.R. promised to take her on a trip to the Virgin Islands in mid-June.

On June 7, Lavin and Dancer paid an unannounced call on Williams. At first she told the agents a cover story—that she worked for Equi-II and was being trained in data processing. But after Lavin and Dancer told her that they had reason to believe Robinson had been involved in the disappearance of at least two young women, Williams began to cry, and the agents were able to coax a more believable story from her—how Robinson had assaulted her with his gun, and how he now planned to take her to the Virgin Islands. And one more thing: at J.R.’s insistence, Williams had been fabricating a diary accusing his friend Irv Blattner of committing various crimes and of threatening her life. Robinson seemed to have sensed that the police were going to use Blattner to implicate him in crimes, and he wanted to use the fake diary to discredit his partner. J.R. had written it out, and Williams had copied it as her own.

As Lavin and Dancer were questioning Williams, they heard a key unlocking the front door. Robinson entered the apartment. The F.B.I. agents identified themselves. Lavin held up J.R.’s draft of the diary and asked if it was his handwriting. Robinson acknowledged that it was. The agents frisked him for weapons but found none. Robinson said he was in a hurry and left the apartment. The agents made no move to stop him. After he had gone, however, they insisted on moving Williams to another location to be kept secret from Robinson. They felt her life might be in danger. Like Stasi and Godfrey, Williams had been asked to sign blank sheets of stationery.

Lavin and Dancer summoned Steve Haymes, who helped interrogate Robinson and then filed a formal report with the Missouri court that had jurisdiction over Robinson’s probation. Haymes alleged that Robinson had violated the terms of his probation by carrying a gun, supplying drugs to Theresa Williams, and lying to his probation officer. Haymes asked the court to revoke the probation and jail Robinson.

A judge did just that after a hearing, but Robinson was released on bail pending appeal. The F.B.I. kept Williams hidden, gave her money, and finally bought her a one-way plane ticket out of town. The Missouri Court of Appeals later overturned the district judge’s ruling on the ironic grounds that Robinson’s constitutional rights had been violated: he had not been allowed to adequately confront his accuser, Theresa Williams.

It was amazing to the frustrated Haymes and the F.B.I. agents that J.R. Robinson was free. To the world at large, he was still a thriving Kansas business entrepreneur with a sumptuous office in Overland Park and a four-acre estate in Pleasant Valley Farms. Just days after the probation-violation hearing, which received no publicity, Robinson was featured on the cover of Farm Journal, a nationally circulated, widely read monthly agricultural magazine. He had persuaded the editors that he was an expert on agricultural finance.

In Kansas, however, Robinson finally came a cropper. After a long investigation, the Johnson County district attorney charged him with fraud in bilking Back Care Systems. A jury convicted him in January 1986. He was then convicted of a second fraud, against an Overland Park man in connection with an Arizona real-estate deal. Because of Robinson’s extensive prior criminal record, a Johnson County judge sentenced him to serve between 6 and 19 years in prison as a habitual criminal. After appeals, he finally went to prison in Kansas in May 1987.

At about this time, another young woman whom Robinson had employed in the early months of that year was reported missing. Catherine Clampitt, 27, had moved to Kansas from Wichita Falls, Texas, after answering a newspaper ad in which Robinson had promised a “great job, a lot of traveling and a new wardrobe,” according to Clampitt’s brother, Robert Bales, with whose family she lived in Overland Park. Clampitt, whom Bales described as intelligent with a “wild side,” often stayed at local hotels for several nights at a time. In mid-1987, after she inexplicably disappeared for weeks, Bales called the police. There was insufficient evidence to link her disappearance to Robinson, who was on his way to prison in Kansas.

Robinson found that his intelligence and persuasive manner worked as well in prison as out. He was an exemplary inmate. After psychological and mental testing showed his intelligence to be well above average, he was put to work as the coordinator of the prison’s maintenance-operations office. There he developed computer programs that would save the Kansas prison system up to $100,000 a year.

Robinson suffered a series of minor strokes while in prison, and during treatment he made an exceptional impression on the prison medical staff. In a nine-page “Report of Clinical and Medical Evaluation,” dated November 1, 1990, two ranking doctors, Ky Hoang, M.D., director of medical services, and George M. Penn, M.D., supervising psychiatrist, wrote that John Robinson was a “model inmate who. . . has made the best of his incarceration. . . He is a non-violent person and does not present a threat to society. . . . He is a devoted family man who has taught his children a strong value system.”

Kansas paroled Robinson in January 1991 after less than four years, but he still faced prison time in Missouri for violating his probation from the Borden fraud a decade earlier. His probation officer was still Steve Haymes, who now stood alone, as the F.B.I. had moved on to other cases. Haymes hadn’t forgotten Robinson, nor had he forgotten Paula Godfrey and Lisa and Tiffany Stasi. Though Missouri prison doctors agreed with their Kansas counterparts that Robinson should be freed, Haymes warned against it.

“I believe him to be a con-man out of control,” Haymes wrote in an official memorandum to a colleague in 1991. “He leaves in his wake many unanswered questions and missing persons. . . . I have observed Robinson’s sociopathic tendencies, habitual criminal behavior, inability to tell the truth and scheming to cover his own actions at the expense of others. . . . I was not surprised to see he had a good institutional adjustment in Kansas considering that he is quite bright and a white-collar con-man capable of being quite personable and friendly to those around him.”

Haymes predicted that Robinson would use his medical problems “to his advantage.” Robinson was imprisoned in Missouri, and sure enough, two of the people he promptly befriended in the penitentiary were the prison doctor, William Bonner, and his 47-year-old wife, Beverly, the prison librarian. She gave Robinson a job in the library.

Missouri kept Robinson in prison for two more years. He was released in the spring of 1993. He was 49 years old. Since his income had stopped during his six years in prison, his wife, Nancy, had been forced to sell their estate in Pleasant Valley Farms. She had taken a job as the manager of a mobile-home development in Belton, Missouri, a suburb south of Kansas City. The development was called Southfork, after the large family home on the Dallas television series, popular in the 70s and 80s. All its streets were named for Dallas characters: Sue Ellen Avenue, Cliff Barnes Lane, and so forth. J.R. joined her there when he left prison.

It was a real comedown from Pleasant Valley Farms, but the Robinsons soldiered on. Their two older children were grown, and the twins were in college, so J.R. and Nancy could make do with less room. They rented lockers at a nearby storage facility for their overflow belongings.

Despite his model behavior in prison, Robinson soon reverted to his old ways. A few months after his release from the Missouri penitentiary, Beverly Bonner, the prison librarian, left her husband, filed for divorce, and in 1994 moved to the Kansas City area and joined forces with Robinson. He gave her the title of president of Hydro-Gro Inc., his hydroponics company, which he had reconstituted. Her mother began getting letters, apparently from Beverly, saying her job with Hydro-Gro was taking her to various cities abroad. She never gave a return address, but directed that all her mail, including her alimony checks, be sent to a post-office box in Olathe. Unbeknownst to William Bonner or any of Beverly’s relatives, J.R. Robinson picked up the checks.

No one heard from Beverly Bonner after January of 1994.

Sheila Faith told friends she had met her “dream man” in John Robinson, though she didn’t give his last name. Robinson likely found Faith through a personal advertisement in a newspaper. Her husband had died of cancer, leaving her with a teenage daughter, Debbie, who was wheelchair-bound with spina bifida. Sheila and Debbie lived in Pueblo, Colorado, on disability payments from Social Security. Sheila was a “very lonely person—she needed companions,” a friend later told The Kansas City Star. John “promised her the world. He told her he was going to take her on a cruise, that he would take care of her daughter, that she’d never have to work, that money was no problem,” the friend recalled.

The Faiths had planned to travel to Texas in the summer of 1994 and stop in Kansas to see Robinson on the way. But without warning early in the summer he drove to Colorado and picked them up in the middle of the night. They were never seen again. It was later learned that their disability checks were being delivered to a postal box in Olathe, Kansas. As with Beverly Bonner, John Robinson picked up the checks.

Pursuing his interest in S&M, Robinson began placing and monitoring advertisements in the Pitch Weekly, a so-called alternative newspaper in Kansas City, whose back pages feature personals columns called “Romance—The Dating Connection” for people seeking conventional relationships, and the “Wildside” for those who prefer the unconventional.

Around September 1, 1995, Robinson spotted an ad which read, “MASTERFUL, SUCCESSFUL, ENTREPRENEURIAL SWM, 35–50, sought by successful, rubenesque beauty.”

Robinson left a voice mail and the “rubenesque beauty” called him back. She went only by the name Chloe Elizabeth to conceal her identity as a successful, well-known, college-educated business-woman in Topeka, Kansas. A driven careerist, never married, accustomed to “dominating” in her business life, she had “decided it was time to seek what [I] truly wanted in [my] personal life—a Dominant with whom I could give up control of the personal side of my life and obey a worthy man who would advance my sexual and personal journey beyond what I was willing to admit wanting on my own.”

Chloe Elizabeth tells me her story, referring to notes, in front of a fire in her spacious home on a cold January day in Topeka.

“I was looking for someone who was in business for himself because I believe that provides a dynamic and a personality that I’m seeking—one that I understand, one that I’m like. [J.R.] made me feel he was pretty close to the type of man I like to date. We had many phone conversations before we actually met for the first time.”

Chloe Elizabeth asked Robinson to send her documents to prove he was who he said he was. “I’m not at all a paranoid person, but in a relationship of D&S, where you’re sincere about what you’re doing, you really need to know the person you’re going to give the control up to is someone who will take good care of you.”

J.R. sent Chloe Elizabeth (by now she had told him her real name and address) an array of material designed to portray him in the best possible light—Chicago newspaper accounts of his appearance before the Queen in London as a 13-year-old Eagle Scout; his hydroponics booklet; a Kansas University brochure picturing two of his attractive children; his appearance on the cover of Farm Journal: and the “proclamation” naming him “Man of the Year.”

Of course, there was no indication of J.R.’s criminal past, no hint that the “Man of the Year” award had been arranged by fakery. Chloe Elizabeth was impressed, and invited J.R. to come to her home at two P.M. on October 25, 1995. By then, nearly two months after their first conversation, she and J.R. had discussed their sexual preferences extensively by phone, and she knew what he, as her “dominant” or “master,” expected of her: “I was to meet him at the door wearing only a sheer robe, a black mesh thong pantie, a matching demi-cup bra, thigh-high stockings, and black high heels. My eyes were to be made up dark, and lips red. I was to kneel before him.

‘He was wearing a dark-navy single-breasted business suit, a starched light-blue shirt with gold cuff links, burgundy striped tie, and polished shoes. Once inside the door, he took a leather studded collar from his jacket and placed it around my neck and attached a long leash to the collar.

“I took him first to the library and a large king chair in front of the fire. Next to it I had put his drink of choice—scotch on the rocks. He drew me to him and we kissed for the first time. After some relaxed small talk, I led him through the rest of the house, ending up in my bedroom on the third floor. There he asked me to remove the few items of clothing I was wearing—one at a time, except for the stockings.

“He then took from his pocket a ‘contract for slavery’ giving my consent to use me as a sexual toy in any way he wished and to punish me in any way he saw fit.

“I read the contract and signed it. He asked if I was sure. I said yes—very sure.

“He put the contract back in his pocket and asked me to remove all of his clothes except his pants. Then he asked me to lie facedown on the bed and spread my arms and legs as wide as I could. Using rope he had brought, he tied my wrists to the head of the bed and my ankles to the foot of the bed.

“Once he had me tied, he asked me to try to move. I couldn’t. He then removed his belt and began to whip me across my bottom, slowly and lightly. I could feel excitement flowing across my skin. Then the blows got harder and closer together. It was painful and I cried. He then lay down beside me and cuddled me and comforted me and told me he loved me.

“He untied the ropes around my wrists and ankles and instructed me to kneel on the bed in front of him. My punishment training for the day was not over. He took a spool of smaller rope as he talked about ‘training’ my large breasts. I wanted to please him. He said that the breasts to be pleasing and well trained must be able to endure pain and to wear marks. He began to wrap the rope tightly around the base of the breast. He wrapped it so tightly that it bulged and turned reddish purple. He crossed the rope in the middle of my chest and began wrapping the other breast. Now both my breasts were like large ripe tomatoes . . . red and ready to burst. The nipples were erect and brown. He took clamps and put one on each nipple. The pain was severe. He thrust the solid leather strap of his belt down upon the top side of my breasts. The pain caused the nipples to expand and become unimaginably restricted by the clamps. Engorged to about three times their normal size, the nipples turned purple and blue. He strapped my breasts again. Only those swats, there would be no more today. To show my gratefulness to his attention, he required one more duty. He stood before the bed and removed his pants. He required that I perform oral sex.

“That was the first date. It was sensational! He had an ability to command, to control, to corral someone as strong and aggressive and spirited as I am.”

I asked Chloe Elizabeth if pain is always part of a BDSM relationship.

“It depends on what you consider pain. I wasn’t interested in being beaten. I don’t love pain. Some women in this lifestyle love pain. For me, there comes a physical state that you’re in where what one might consider pain on your body isn’t painful. It’s exciting.”

Before he left, Robinson told Chloe Elizabeth she had been “stupid” for allowing him to do all he had done. “I could have killed you,” he said. Though she hadn’t told him, Chloe Elizabeth never felt threatened by J.R., even when she was tied defenseless to her bed. That’s because she had stationed a male friend in the house to be alert for any sign of excessive behavior. He made a note of J.R.’s license-plate number while Chloe Elizabeth and J.R. were upstairs.

J.R. and Chloe Elizabeth began seeing each other at least twice a week. But she gradually became suspicious of him. Through a contact in state government, she ran his license plates and found that his car was registered in his wife’s name as well as his own. He had told her he was divorced. After they had pledged their love for each other repeatedly, J.R. suggested to Chloe Elizabeth that they should exchange lists of all their assets. She balked, suspecting this was a first step by J.R. to get his hands on her money.

In BDSM relationships, dominants sometimes take control of submissives’ financial assets. A sample master-slave contract featured on a BDSM Web site stipulates, “All of the slave’s possessions . . . belong to the master, including all assets, finances, and material goods.”

“It is not unusual for [the relationship] to include financial decisions,” says Jes Beard, a Chattanooga, Tennessee, lawyer who has represented four clients in BDSM relationships, including a woman who had a relationship with Robinson. The woman, who met him on the Internet, says she gave him $17,000 from an I.R.A. to invest for her and never saw it again. “The dominant will tell them, Here’s where you need to do your banking, here’s the insurance you need, here’s the whatever,” Beard told me.

Another lawyer for BDSM clients, Lloyd E. N. Hall of Atlanta, who practices BDSM himself, says that, while relationships vary widely, total financial dominance is unusual. 7ldquo;It’s fairly the exception that a person actually transfers their personal assets or anything like that when they enter into a master-slave relationship.”

Chloe Elizabeth was determined to avoid any financial relationship with Robinson. He invited her to travel to Europe with him. After she tentatively agreed, he suggested that she sign several blank sheets of stationery and give him a list of her relatives’ addresses so that he could keep them informed of her whereabouts. She balked and never traveled with him.

He told her he would be away in Australia for a while. She discovered that he had not left Kansas. She telephoned his office. Someone answered but said nothing. An hour later her phone rang.

“How dare you check up on me!?”

“J.R., what are you talking about?”

“You’re checking up on me. You know I record every phone call that comes in to any of my businesses. I know that was you. I’m really pissed that you, would check up on me after all we’ve gone through.”

“I don’t have a clue what you’re talking about.”

“Don’t ever check up on me again!”

She finally learned about his criminal record and told him in February 1996 that she wanted to stop seeing him. Their relationship fell off to occasional E-mails.

In 1996, J.R. and Nancy Robinson moved from the Southfork mobile-home development in Missouri to a similar development in Olathe called the Santa Barbara Estates, where all the streets were named for California cities. The Robinsons took up residence at 36 Monterey. They installed wind chimes near the front door and a statue of St. Francis of Assisi in the front yard. Their Christmas decorations were considered the most spectacular at Santa Barbara, where Nancy was the manager, as she had been at Southfork.

The Robinsons also bought 16 acres of farmland with a fishing pond an hour south of Olathe. They put a mobile home and shed on the property, and he occasionally took friends fishing there.

Thanks to the Internet, J.R.’s sexual horizons expanded dramatically beyond the personal ads of the Pitch Weekly and other newspapers. He maintained five computers in his Santa Barbara home, three desktops and two laptops, and trolled the BDSM Web sites for hours. His handle was “Slavemaster.”

Robinson met Izabela Lewicka on the Internet in the early months of 1997 while she was a freshman at Purdue University in Indiana. Born in Poland, Lewicka had come to Indiana with her parents when she was about 12. At Purdue she was studying fine arts but also took a great interest in computers and often was at her monitor late into the night.

In the spring of 1997, Lewicka announced to her parents that she had been offered an “internship” by a man in Kansas. She wouldn’t give details, except that she would be able to use her artistic training. Though her parents tried to dissuade her from going, she drove to Kansas that June, taking clothing, personal items, and nearly all her paintings. She left an address in Overland Park, Kansas, on Metcalf Avenue, a main north-south artery. Her parents wrote letters to that address but received no reply. In August they drove to Kansas to look for their daughter and found that the address on Metcalf was that of a Mail Boxes Etc., whose manager refused to give them Izabel’s address or telephone number. They returned to Indiana without contacting the police.

In fact, Robinson had installed Lewicka in an apartment in south Kansas City where they regularly engaged in BDSM sex and he photographed her nude in bondage, all in accord with a “slave contract” enumerating 115 provisions of his dominance and her submission. He paid her bills, and when they weren’t having sex, she led a life of leisure, spending a lot of time reading gothic and vampire novels she purchased at a rare-and-used-book shop in Overland Park. Usually dressed in black, sometimes with a black leather dog collar with metal studs, she told the owners that she was proud to be from Dracula’s part of the world.

In January 1999, J.R. moved Lewicka into an apartment in Olathe. He referred to her variously as his adopted daughter, his niece, and a graphic designer who worked for his new company, Specialty Publications, which covered the modular-home industry. The following summer, she introduced Robinson to her bookstore friends and told them he would be buying her books in the future because she was moving away.

Though the Olathe apartment was leased through January 2000, Lewicka suddenly disappeared in August 1999. Robinson told one of his business associates that she had been caught smoking marijuana with her boyfriend and had been deported. When Robinson released the apartment to the managers so they could prepare it for the next tenants, they found it remarkably, immaculately, memorably clean.

Suzette Trouten, a 27-year-old home-care nurse who lived in Monroe, Michigan, near Detroit, amused herself by collecting teapots, playing with her two Pekingese dogs, and engaging in BDSM sex. Trouten was so deeply involved in the BDSM lifestyle that she carried on relationships with four dominants at once. She had pierced her nipples, her navel, and five places in and around her genitalia, piercings which could accommodate rings and other devices used in BDSM rituals. A photograph of Suzette Trouten with nails driven through her breasts had circulated on the Internet.

Trouten and J.R. Robinson met on the Internet in the fall of 1999, just weeks after Izabela Lewicka disappeared. J.R. invited Trouten to Kansas. He might have a job for her, he said, as a companion and nurse to his elderly father, a rich man who liked to travel but needed constant care. (J.R.’s father had actually been dead for 10 years.)

J.R. flew Trouten to Kansas City and had a limousine meet her at the airport. The job interview went well, she told her mother by phone. J.R. and his father, whom she did not meet, had a yacht, and she would be sailing with them in the Pacific off California, possibly going all the way to Hawaii. Suzette and J.R. agreed that he would pay her $60,000 a year and provide her with an apartment in the Kansas City area and a car.

Back in Michigan, preparing to return to Kansas, Suzette told her mother, Carolyn Trouten, that she feared homesickness but hoped the money she would earn from Robinson would enable her to complete her nursing degree. She drove to Kansas in a Ryder truck, paid for by J.R., on February 13 and 14. In the truck were her clothing and books, plus her teapot collection and her two Pekingese dogs, Harry and Peka. She also took along her BDSM equipment—whips, paddles, canes, collars, and the like.

J.R. had registered Trouten at the Guesthouse Suites, Room 216, in Lenexa, a Kansas City suburb just west of Overland Park and north of Olathe. J.R. boarded Trouten’s dogs at a local animal shelter. She could take them on the trip to California and on the yacht, he said, but the Guesthouse Suites didn’t allow pets. J.R. told his new employee to prepare to leave two weeks hence. He directed her to get a passport. He had her do some computer work at his office. He had her sign a slave contract covering their BDSM relationship. He also had her sign more than 30 blank sheets of stationery and address more than 40 envelopes to her relatives and friends; she would be too busy while they were traveling to worry about correspondence, which he would take care of.

Suzette kept in close touch on the Internet with a BDSM contact, a woman named Lori who lived in Canada and who knew about J.R. Robinson and Suzette’s job in Kansas. Suzette also spoke to her mother, Carolyn, every day by phone. Suzette called Carolyn at around one A.M. on Tuesday, February 29.

“Everything’s fine,” Suzette said. “John is nice. I’m not as lonesome as I thought I’d be.” They were leaving for California Wednesday or Thursday. Suzette would call frequently while they were traveling.

On the afternoon of Wednesday, March 1, J.R. Robinson paid Trouten’s final bill at the Guesthouse Suites and checked her dogs out of the animal shelter. Neither the hotel clerk nor the animal-shelter attendant had seen Trouten. Later that afternoon, an animal-control officer was dispatched to Santa Barbara Estates, where someone had left two Pekingese dogs without identifying collars in a portable kennel outside the main office.

Carolyn Trouten heard nothing from her daughter in early March. Nor did Suzette’s Canadian friend Lori. Both telephoned J.R. Robinson, who toyed with them. He told them that at the last minute Suzette had decided against taking the job he had offered her and had run off with a man named James Turner. Neither Carolyn nor Lori believed the story. Around the middle of March, they began receiving E-mails and letters that were signed “Suzette” but, they knew, were not from Suzette. They didn’t sound at all like her.

“I believed this person [Robinson] had done something to Suzette,” Lori would testify later.

Suzette’s family contacted the Lenexa Police Department and reported her missing. Unlike the neighboring Overland Park department, which had received similar reports of missing women associated with John Robinson in the 80s, and had given them less than full attention, Lenexa detective David Brown immediately began a thorough inquiry into the disappearance of Suzette Trouten. Brown obtained Robinson’s rap sheet, got in touch with Overland Park detectives, and saw the possible connections with other cases of missing women. A task force of representatives of several local, state, and federal law-enforcement agencies, including the F.B.I., was urgently organized under the supervision of Johnson County district attorney Paul J. Morrison, an eminent prosecutor in the Kansas City area. A native of Dodge City, Morrison, 45, had been Johnson County’s chief law-enforcement officer for 11 years and had convicted several high-profile murderers.

One of the task force’s first moves was sending two detectives to Missouri to see Steve Haymes. “You seem to have had this guy pegged from the beginning,” one of the detectives remarked after Haymes briefed them on Robinson’s criminal history, going back to the 60s. Detective Brown instructed the family of Suzette Trouten to tape their conversations with Robinson and send all E-mails to and from him to the Lenexa police. Brown coached them on inducing Robinson to divulge details that might be clues to Suzette’s whereabouts.

In February 2000, as Suzette Trouten had been getting settled in Kansas and preparing, she thought, to leave with Robinson for California, Robinson had begun conversing on the Internet with a woman named Jeanne, a professional from the Southwest. Divorced and 34 years old, Jeanne was looking to establish a BDSM relationship with a man who might also be able to employ her professionally. Robinson identified himself to Jeanne as James Turner. After they explored their BDSM likes and dislikes extensively via phone and Internet, Robinson invited Jeanne to come to Kansas. She visited for a long weekend, Thursday, April 6, until Tuesday, April 11. He put her up in a hotel, where they engaged in various kinds of sexual interplay ranging from intercourse to fellatio to flogging.

Toward the end of her stay, they agreed that Jeanne would move to Kansas and work for Robinson’s companies Hydro Gro and Specialty Publications. When she returned to Kansas in mid-May, Robinson installed her in the Guesthouse Suites in Lenexa, where he had kept Suzette Trouten in February. They had sex on the afternoon of Tuesday, May 16, and intermittently thereafter. One day that week he didn’t show up. On Friday, May 19, however, Robinson telephoned Jeanne, told her he was on his way, and instructed her that when he arrived she should be nude and kneeling in a corner of the room with her hair pulled back.

When he entered the room he grabbed her by the hair and began flogging her across her breasts and back. He then insisted that she pose for photographs, even though she had told him she didn’t want him to take pictures. He was particularly interested in photographing the marks his floggings had left on her body.

Robinson then told Jeanne that he didn’t like her attitude and that if she didn’t change she would have to move back home. He left the hotel room, saying he would return.

Jeanne became hysterical. She had moved to Kansas to be with this man and work for him. But he seemed interested only in punishing her and pleasing himself. Her body burned from his beatings, and he was threatening to banish her.

Jeanne ran to the front desk of the hotel, sobbing uncontrollably. She insisted on seeing the registration card for her room. She discovered that the man she had been seeing was named John Robinson, not James Turner. She tried to call the police but was too upset to complete the call. The desk attendant did it for her.

Within minutes, Detective David Brown arrived at the Guesthouse Suites. Two months into his intensive investigation of John Robinson, Brown knew his subject intimately. After hearing a brief version of Jeanne’s story, told through tears, he collected her belongings and moved her to another hotel.

Brown interviewed Jeanne the next day, Saturday, May 20, and on into the following week. She explained how Robinson had beaten her far beyond her desires. She didn’t like pain or punishment or marks on her skin. “I’m a submissive, not a masochist,” she said.

The long-overdue investigation of J.R. Robinson was reaching its climax. A little more than a week later, on Friday, June 2, a convoy of nine police vehicles entered the grounds of the Santa Barbara Estates in Olathe and surrounded the Robinsons’ residence, at 36 Monterey. Police detectives placed a dumbstruck John Robinson under arrest, charged him with sexual assault, and took him in handcuffs to the Johnson County jail. Other detectives began executing a warrant authorizing them to search the house. They seized all five computers. They also found a blank sheet of stationery signed by Lisa Stasi more than 15 years earlier—in January 1985—and receipts from the Rodeway Inn in Overland Park showing that Robinson had checked Stasi out of the hotel on January 10 of that year, the day after she disappeared with him into the snow.

As the search of the Robinson house continued, Lenexa detectives Dan Owsley and Dawn Layman, armed with a second search warrant, were wielding a bolt cutter on a padlock securing Robinson’s 10-by-15-foot locker at a nearby storage facility in Olathe. Inside they found a trove of items linking Robinson to Suzette Trouten, now missing two months, and Izabela Lewicka, who had not been seen since the previous August. There were Trouten’s birth certificate and Social Security card; sheets of blank stationery signed “Love ya, Suzette”; a two-page slave contract signed by Trouten; and a stun gun. There were Izabela Lewicka’s Kansas driver’s license; photographs of Lewicka nude in bondage; a six-page slave contract listing 115 rules, sexual and otherwise, she was obliged to obey. And there was a pillowcase and several BDSM sex implements.

The next morning, Saturday, June 3, another convoy of police vehicles made its way an hour south from Olathe to the remote 16-acre plot of land that the Robinsons owned off a country lane near the town of La Cygne.

There, with yet another search warrant, Detective Harold Hughes, a forensic crime-scene investigator for Johnson County, located two yellow 55-gallon metal barrels near a toolshed across from the mobile home. Using a pair of heavy pliers, he pried open one of the barrels. Inside was a female body, nude, with its head down, immersed in about 14 inches of fluid, the result of decomposition.

Hughes opened the second barrel. He first saw a pillow and red-and-green pillowcase. He removed them and found another female body, this one clothed, also soaked in the fluid of its own decay. Hughes photographed and fingerprinted both barrels and resealed them, leaving the contents inside. Using a black Magic Marker, he labeled the barrels “Unknown 1” and “Unknown 2.” The Robinson property was sealed and placed under guard.

The investigation was still top secret. However, a detective telephoned Steve Haymes at home that Saturday evening to confide that they had found bodies. He wanted Haymes to know before it hit the newspapers. Haymes was stunned. “It confirmed what I had always believed,” he recalls, “but the move from theory to reality was chilling.”

Early Saturday evening, as Detective Hughes was completing his search of the Robinson property, a pager beeped in the home of Mark Tracy, the deputy prosecuting attorney of Cass County, Missouri, a few miles across the state line. It was the county sheriff’s communications center asking Tracy to telephone Johnson County D.A. Paul Morrison.

“Morrison himself, not just his office?” Tracy asked.

“Morrison himself.”

Tracy felt a bit intimidated. Paul Morrison was a towering figure in Kansas City law-enforcement circles.

Tracy dialed the number and Morrison answered.

“I’m working a case,” Morrison said. “It’s kind of a big deal. I need your help to get a search warrant to look in a storage locker in your county. . . . I won’t go into details, but you might want to alert your boss.”

On Sunday morning Mark Tracy received a delegation from Morrison—his deputy Sara Welch and several detectives—at the Cass County prosecuting attorney’s office. The affidavit they gave Tracy was the longest search-warrant affidavit he had ever seen. It indicated, among other things, that John Edward Robinson Sr. was believed to have killed several women; that he had used the Internet to lure them to Kansas for BDSM sex; that he maintained a locker thought to contain evidence at Stor-Mor-for-Less in Raymore, Missouri, a Kansas City suburb; and that he had paid for the locker with a company check so as to conceal it was his.

Back across the state line in Kansas that Sunday, at the medical examiner’s office in Topeka, Donald Pojman, M.D., the deputy coroner, a bespectacled man with black hair, mustache, and beard, removed the body from the barrel marked “Unknown 1.” Across the face he found a large swatch of cloth secured by a rope around the head, possibly a blindfold. The hair was tied in an 18-inch ponytail. There were several rings on the body—one on a little finger, one on a ring finger, one through piercings in each nipple, and five rings through piercings in and around the genitalia.

Dr. Pojman determined that the woman had received a massive blow, probably with a large hammer, to the left side of the head between the forehead and the temple. The skull was fractured and a circular section of it was actually driven into the brain. The woman could have died from any one of three causes: bleeding, damage to the brain tissue, or swelling of the brain following the blow. There was no sign that she had had an opportunity to defend herself. Dr. Pojman estimated that she had been dead anywhere from a few months to a year.

Unknown 2 also had died from a blow to the left side of the head that had fractured her skull. In fact, there appeared to have been two blows, overlapping, forming an oval indentation. The left side of her jaw also had been fractured. Again, there was no sign that she had been able to defend herself.

It was late Sunday night when Dr. Pojman finished. Forensic odontologists would attempt to identify the bodies with dental records the next day.

Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Mark Tracy of Cass County served the search warrant at Stor-Mor-for-Less in Raymore at eight A.M. Monday. It was much colder than normal for early June, and no one was dressed for it. Tracy led the Kansas task-force detectives to John Robinson’s locker, E-2, and opened it. It was 10 by 20 feet, even bigger than the locker in Olathe, and filled with clutter. The shivering detectives began gingerly removing the contents and either inventorying items as potential evidence or putting them aside.

After 40 minutes, Tracy could make out what appeared to be three barrels in the shadows at the back of the locker. He also began to smell the unmistakable odor of rotting flesh.

Tracy halted the search and called his boss, Cass County prosecuting attorney Chris Koster, who was in his car en route to the Kansas City airport to catch a flight to Florida on another case. Tracy had been briefing Koster by phone since Paul Morrison’s call on Saturday, but it had not appeared until now that bodies would be found in the Missouri storage locker.

“There are barrels and there are going to be bodies in them,” Tracy told Koster. “You’ve got to come back.”

Koster canceled his trip and was at Stor-Mor within the hour. There was an intense discussion of whether Kansas or Missouri authorities would control the investigation from then on. Koster and Tracy determined that the likely presence of bodies on Missouri soil meant the case was no longer just a search for evidence related to Kansas homicides. Missouri would control the crime scene. Koster summoned a team from the Kansas City crime lab’s major-case squad. Its leader looked the scene over and said, “Has anybody ordered food? It’s going to be a long day.”

As it happened, a police van loaded with pizza, soft drinks, and coffee was already there as the investigators resumed their slow work. It was afternoon before they had emptied the locker of everything but the barrels, which were made of metal and had been wrapped in clear plastic. Sealed with gray duct tape, they were sitting on piles of kitty litter, which apparently had been intended to minimize the odor.

A crime-lab technician opened one of the barrels. The first things he saw were a light-brown sheet, a pair of glasses, and a shoe. He removed the sheet and then grasped the shoe, only to find that it was attached to a human leg. It was decided to reseal the barrel and take all three containers to the Kansas City medical examiner’s office. One of the barrels was leaking fluid, and it was feared that their bottoms might have corroded and would give way when lifted. A police officer was sent to a nearby Wal-Mart to purchase three plastic children’s wading pools. They were slipped under the barrels before they were placed aboard the crime-lab van.

Thomas W. Young, M.D., the chief Kansas City medical examiner, a veteran of 3,800 autopsies, opened the barrels. Chris Koster and Mark Tracy watched from behind two panes of glass. “When they opened those barrels . . . ,” Tracy told me later. “I’ve been around homicide scenes before, and I’ve smelled pretty old, decayed bodies, but they’d been exposed to the open air. These had been in barrels. And, man, it was an extraordinarily strong smell and very uncomfortable.”

Each barrel contained the severely decomposed body of a female who had been beaten to death, probably with a large hammer. They obviously had been dead for several years. The first body was fully clothed. On the second body was a T-shirt reading, CALIFORNIA STATE OF MIND. In the mouth was a denture broken in half. The third was the body of a teenager wearing green pants and a silver beret. There were no defensive wounds; none of the victims had been able to defend herself.

Earlier that Monday, a forensic odontologist in Topeka had identified the two bodies found on Robinson’s property in Kansas as Suzette Trouten and Izabela Lewicka. Later in the week, a Missouri forensic odontologist identified two of the bodies found in Robinson’s storage locker as Beverly Bonner, the former prison librarian, and Sheila Faith. Sheila’s wheelchair-bound daughter, Debbie, was identified with a skeletal X-ray.

Johnson County district attorney Paul Morrison and Cass County prosecuting attorney Chris Koster charged John Robinson with the murder of all five, as well as of Lisa Stasi, who has been missing since 1985 and whose body has not been recovered. (Her daughter, Tiffany, now 16 and named Heather, still lives with Don and Helen Robinson. DNA tests recently proved that Carl Stasi is her biological father. She is aware of the current investigation into John Robinson’s past.) Both Morrison and Koster will seek the death penalty.

In the face of the evidence against him, Robinson, at a March hearing, “stood silent,” and Judge John Anderson III, son of a former Kansas governor, entered a not-guilty plea on his behalf. Asked by Vanity Fair for a response to any or all charges against Robinson dating back to the 1960s, his lawyer Ronald F. Evans, chief attorney of the Kansas Death Penalty Defense Unit, said he had no comment.

As for Paula Godfrey and Catherine Clampitt, also missing since the 80s, authorities are still investigating their disappearances and haven’t charged Robinson in those cases. He was placed in solitary confinement in the Johnson County jail. No trial date has been set.

Afew days after Robinson’s arrest, a spokesman for his family issued a written statement defending him: “We have never seen any behavior that would have led us to believe that anything we are now hearing could be possible. . . . While we do not discount the information that has and continues to come to light, we do not know the person whom we have read and heard about on TV. . . . [John Robinson is a] loving and caring husband and father. . . . We wait with each of you for the cloud of allegations and innuendo to clear, revealing, at last, the facts.”

In June 2000, the authorities charged him with the murders of the five women. Robinson was put on trial two years later, and the prosecution team presented much evidence against the accused. On October 29, 2002, the jury found John Robinson of killing three women. The court eventually sentenced him to death in January 2003.

As of now, he is on death row in Kansas. Heavy reported that Robinson is currently in the El Dorado Correctional Facility.