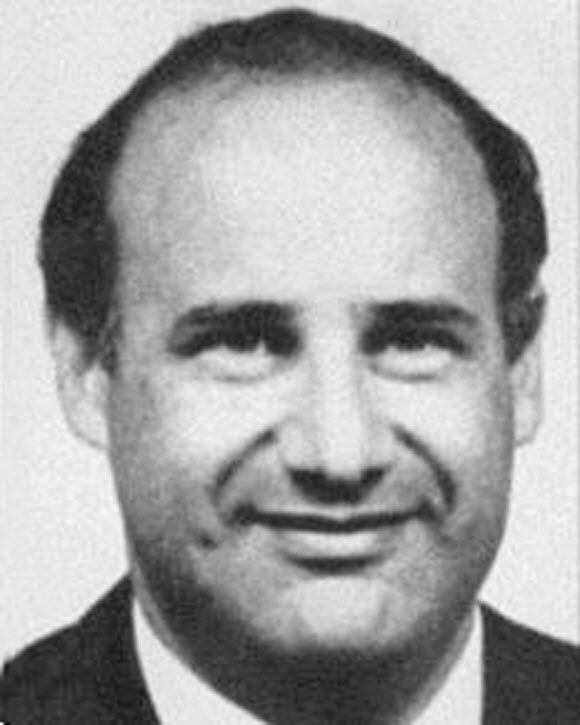

For nearly two decades, Jean-Claude Romand lived a double life. He wasn’t a killer in the traditional sense. He was a father, a husband, a son and, supposedly, a successful doctor at the World Health Organization in Geneva. But on a cold January morning in 1993, a fire in a quiet French village uncovered the horrifying truth Romand was not who he said he was.

He never finished medical school. He never worked for the WHO. His life was a web of lies. And when it began to unravel, he chose murder over confession.

Early Life

Jean-Claude Romand was born in 1954 and raised in Clairvaux-les-Lacs, a village in eastern France. His upbringing was largely uneventful. His father managed a timber business; his mother stayed at home, often unwell. Jean-Claude later said he was taught never to lie but also to avoid saying anything that might cause distress. That conflicting message stayed with him.

He was quiet, intelligent, and seemed introspective. He had a strong emotional attachment to his dog, which he later said was the only being he confided in during childhood. Friends and family viewed him as gentle and well-mannered. Few, if any, imagined he was capable of violence.

The First Lie

In 1971, Romand graduated from secondary school and began studying medicine in Lyon. There, he reconnected with Florence, a distant cousin been in love with since he was 14. She was studying pharmacy. Eventually, they began dating, and later, married.

Romand’s academic career began normally until his second year. He missed a crucial final exam. Later, he said he had injured his wrist in a fall. But even if true, he could have taken the exam orally. He didn’t. And instead of facing the consequences, he made a quiet decision to lie.

Romand told his family he had passed. Then, instead of moving forward in the program, he reenrolled in the second year of medical school every year for eleven straight years. The school allowed it due to its outdated registration system. Each year, Romand attended classes, took notes, and loitered near exam halls. He did everything a real student would do except take the final exams.

Eventually, his friends and family assumed he had graduated. And when it became too difficult to maintain the charade of being a student, Romand escalated the lie. He told them he had become a doctor and researcher at the World Health Organization.

Fake Career

He kept pretending. In 1980, Romand married Florence and started a family. They had two children Caroline, born in 1985, and Antoine, born in 1987. They moved into a comfortable home near the Swiss border.

To maintain appearances, Romand would leave the house for “work trips” in Geneva. He drove to the WHO headquarters, entered the public lobby, drank coffee, collected pamphlets, and sat for hours. Occasionally, he traveled to airports and read travel guides in hotel rooms, pretending to be abroad. He called home with weather updates from the “countries” he was “visiting.”

Florence never met any colleagues. He never invited anyone over. When questioned, Romand claimed his work was too confidential possibly involving intelligence agencies. She once joked he might be a spy.

The truth was darker Romand was unemployed, and had been for over a decade.

Money and Fraud

At first, Romand lived off money from an apartment his parents had bought for him during his “studies.” But by the late 1980s, he needed more. That’s when the fraud began.

A family friend diagnosed with cancer trusted Romand to obtain experimental medicine from the WHO. Romand accepted 60,000 francs in exchange for sugar pills. The friend died shortly after. It wouldn’t be the last deception.

Romand began telling friends and relatives that he had access to lucrative investments through contacts at WHO. He promised 18% annual returns. Many people including his father-in-law, friends, and even his mistress gave him money to invest. Romand never invested anything. He spent the money on luxury goods, a BMW, and his family’s lavish lifestyle.

Over time, Romand swindled more than 2.5 million francs. His fraud functioned like a Ponzi scheme money from one investor was used to repay another when necessary. But eventually, people began asking questions.

Rising Pressure

Romand began an affair with Corinne, a divorced mother of two. He told her he was investing money for her. When she sold property for 900,000 francs, she gave it to Romand with the condition she could withdraw it anytime. He agreed. But the money was already gone.

Around the same time, Florence’s friend became suspicious. She had contacts at the WHO and discovered Jean-Claude was not listed as an employee. When she shared this with Florence, the lie was under threat.

Then, Romand’s father-in-law asked to withdraw his investments. Romand had nothing to repay him. Shortly afterward, the father-in-law died in a suspicious fall down the stairs. Romand was the only witness.

The walls were closing in. Corinne demanded her money. Florence was growing wary. Romand could not keep lying. But instead of confessing, he made a horrific choice: to eliminate everyone who knew the truth.

The Murders

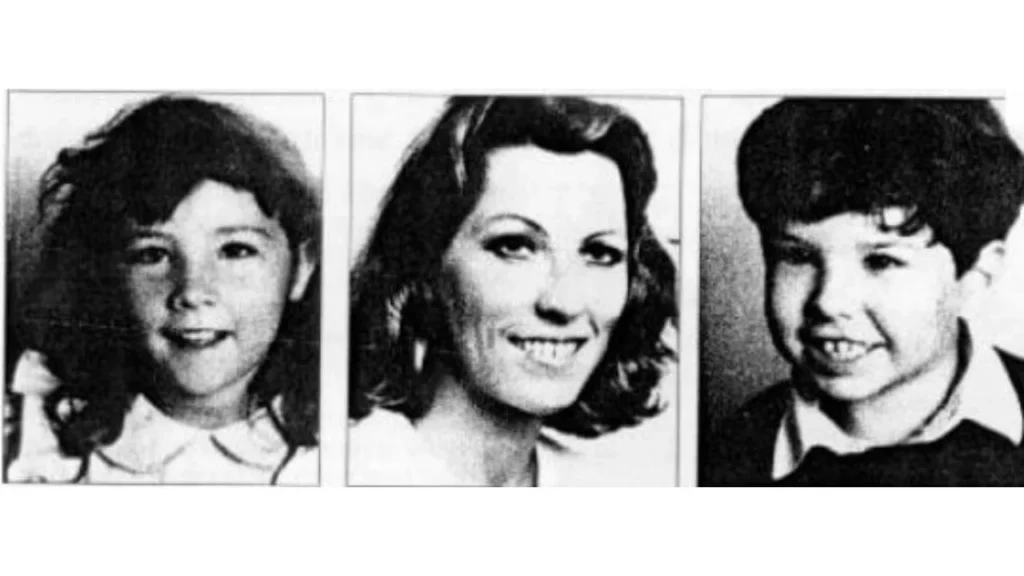

On January 9, 1993, Romand killed his wife. While she lay in bed, he beat her to death with a rolling pin. He then washed the weapon, returned to the bed, and slept beside her body.

The next morning, he got up and watched cartoons with his children. Then he drugged their drinks with barbiturates. When they became groggy, he shot them both in their beds. Caroline was 7. Antoine was 5.

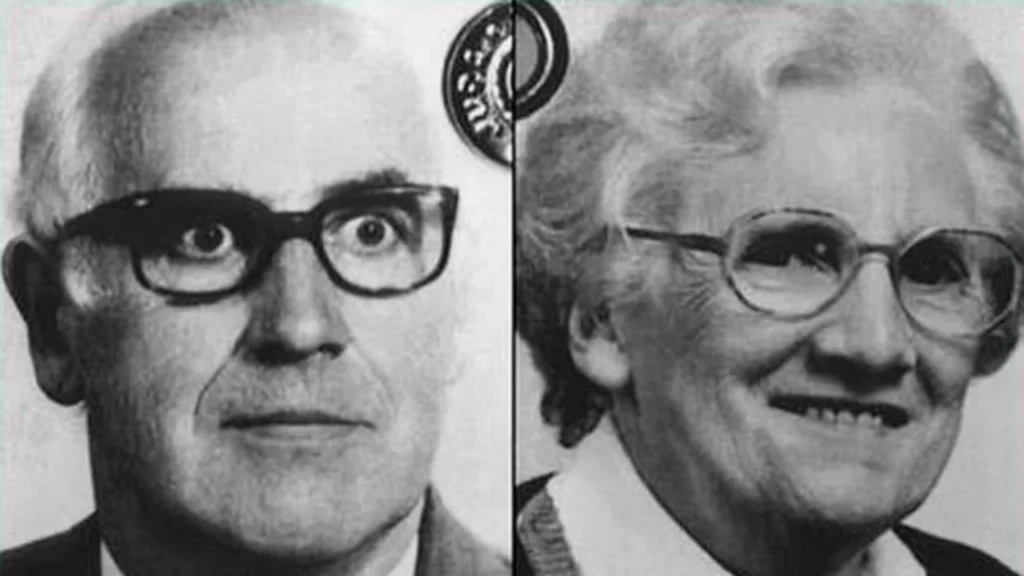

He wasn’t finished. That day, he drove to his parents’ home. They welcomed him for dinner. After they ate, he shot them both, then shot the family dog when it panicked.

After the murders, Romand cleaned the gun, and called Corinne. He invited her to a dinner party. She agreed.

Romand drove her to a remote road. He told her to close her eyes for a “surprise.” Then, he pepper-sprayed, tased, and tried to strangle her with a cord. Miraculously, Corinne fought him off. Romand backtracked, claiming he had cancer and was acting out. Playing along to survive, Corinne convinced him to drive her home.

The next day, Romand returned to his home. Overwhelmed, he spent hours watching TV, and repeatedly called Corinne, claiming he didn’t want to hurt her.

Then, nearly 48 hours after the first murder, Romand poured gasoline through the house, swallowed expired sleeping pills, and lit a match.

But he did not die.

He closed the bedroom door, blocked the gap to keep smoke out, and opened a window when he heard sirens doing everything possible to survive the fire.

The Arrest

Firefighters found Romand unconscious, but alive. His wife and children were found dead. Investigators quickly realized the fire didn’t cause the deaths. Florence and the children had been killed before the fire started. The wounds didn’t match fire-related injuries they were from blunt force trauma and bullets.

Later that same day, Romand’s parents were found shot in their home. Even the family dog had been killed.

Romand claimed at first that armed men had broken into his house, murdered his family, and set it on fire. But evidence contradicted his story. When police confronted him with the facts, he shifted explanations multiple times. Eventually, after seven hours of questioning, he confessed.

Mental Health

Psychiatrists who evaluated Romand diagnosed him with narcissistic personality disorder. They said he was less concerned with the murder victims than with impressing the psychiatric staff. He was deeply invested in appearing intelligent and composed, even after killing five people.

During interviews, Romand said he felt “liberated” after the truth came out. The burden of the lie maintained over 18 years had finally ended.

The Trial

Romand’s trial began in 1996. It gripped France and drew international attention. People were stunned: how could a man fool so many for so long? How could he kill his entire family to preserve a false identity?

After five hours of jury deliberation, Jean-Claude Romand was found guilty of five counts of murder, attempted murder, and arson. He was sentenced to life in prison, with no possibility of parole for 22 years.

Romand showed little emotion during sentencing.

Life After Prison

In 2019, after serving his minimum sentence, Jean-Claude Romand was granted parole. He was 65 years old. His release sparked public outcry in France. He had murdered five people including two young children to maintain a fabricated life. Some argued that his crimes were so calculated and self-centered that freedom was unjustified.

Romand now lives in anonymity under supervision. Details of his current life are scarce by legal design.

Legacy of a Lie

The Jean-Claude Romand case remains one of the most chilling examples of pathological deception in modern criminal history. For 18 years, he constructed and protected a fake life not through brilliance, but through obsessive control, manipulation, and charm. When threatened with exposure, he didn’t fold. He killed everyone close to him rather than face humiliation.

His story has inspired books, films, and documentaries. The French novelist Emmanuel Carrère published a widely acclaimed non-fiction book, The Adversary, in 2000, which explores the psychology behind Romand’s lies and crimes.

The question remains: how far can someone go to protect a lie? In Romand’s case, the answer was: all the way.