A police search of the Monastery of the Virgin in the Pines was carried out under a warrant connected to the illegal trade of olive oil and imported goods. The monastery belonged to an Old Calendarist sect led by Abbess Mariam Soulakiotis, known within the community as Mother Mariam of Keratea.

The inspection began at dawn and lasted through the day. Officers documented confined residents, unsanitary living quarters, and extensive financial records. Among the evidence were hundreds of property deeds, numerous wills transferring assets to the monastery, and signs of physical neglect among the inhabitants. Thirty-six children were taken into protective custody.

The findings prompted a wider investigation into the convent’s activities during the preceding two decades. Witness statements and financial records linked the abbess to coerced donations, unlawful imprisonment, and multiple deaths attributed to starvation and medical neglect. What started as an inquiry into a commercial offense developed into a criminal case involving fraud, homicide, and religious exploitation.

The Raid

The search began at approximately six o’clock in the morning on December 4, 1950. Police, accompanied by a deputy prosecutor, a coroner, and a district judge, entered the monastery grounds at Keratea, southeast of Athens. The operation followed a six-month inquiry into irregular financial activity connected to the convent’s trade in olive oil and other commodities.

The monastery complex consisted of a main chapel, several dormitories, storage buildings, and an adjoining residence used by the abbess. Officers divided into teams to document each area. The first group inspected the basement beneath the western wing, where they found elderly women in restraints. Chains were fixed to wall rings the prisoners were malnourished and exhibited bruising and open sores. Medical staff later classified their condition as critical.

In adjacent rooms, investigators found improvised wooden enclosures measuring roughly one by two meters described in police notes as “small boxes used for solitary confinement.” Two occupants were discovered alive inside.

On the upper floor, thirty-six children most under the age of twelve were located in shared quarters. They were described in subsequent hospital records as underweight, anemic, and showing signs of chronic neglect. All were removed from the site and transferred to medical care in Athens.

During the property search, officers catalogued over 300 land titles and several hundred wills naming either the monastery or the abbess as beneficiary. They also recovered large sums of cash, gold jewelry, and household valuables stored in locked chests. Outside the main building, shallow graves were identified near the boundary wall a coroner’s team exhumed remains for examination.

The abbess, Mariam Soulakiotis, was detained in her private quarters without resistance. She identified herself as Mother Mariam of Keratea, Superior of the Order, and stated that all residents had entered the monastery voluntarily. The officials concluded the initial inspection late that evening. Their preliminary report noted “evidence of extended confinement, malnutrition, and unauthorized possession of multiple properties.”

The documentation from this single day became the foundation for the broader criminal investigation that followed.

The Farm Girl and the Monk

Mariam Soulakiotis was born around 1883 in rural Greece, most likely in the Peloponnese region, to a family of limited means. Surviving parish and census records list her as the daughter of agricultural laborers. In her early years, she worked both on the family farm and in nearby textile workshops, typical employment for women of her background at the time.

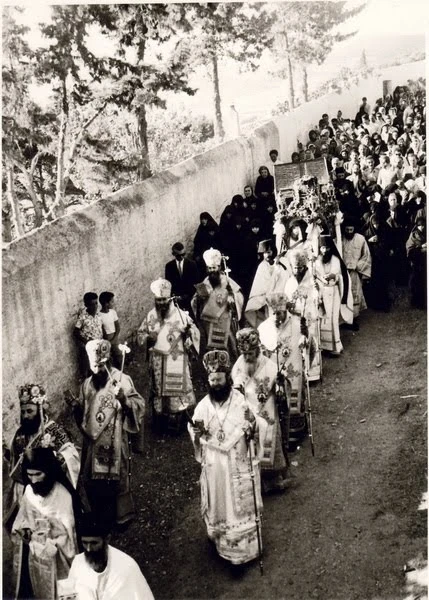

At approximately twenty-three years of age, Soulakiotis came into contact with Matthew Karpathakis, a monk who had been expelled from the Greek Orthodox Church for rejecting the adoption of the Gregorian calendar. Greece had officially aligned with the new calendar in 1923, a move that divided clergy and congregations across the country. Karpathakis and his followers calling themselves the Old Calendarists continued to observe the traditional Julian calendar, forming an independent ecclesiastical structure outside the authority of the official church.

Soulakiotis joined his circle during this schism and took religious vows within the movement. Within a few years, she became one of Karpathakis’s most trusted associates, assisting in his plan to establish a separate convent.

In 1927, land records show that Karpathakis and Soulakiotis acquired property between the town of Keratea and the rural village of Kaki Thalassa. There they founded the Convent of the Virgin in the Pines formally registered as a religious house under the Old Calendarist sect. The location, a hillside surrounded by forest, was chosen for its isolation and proximity to Athens.

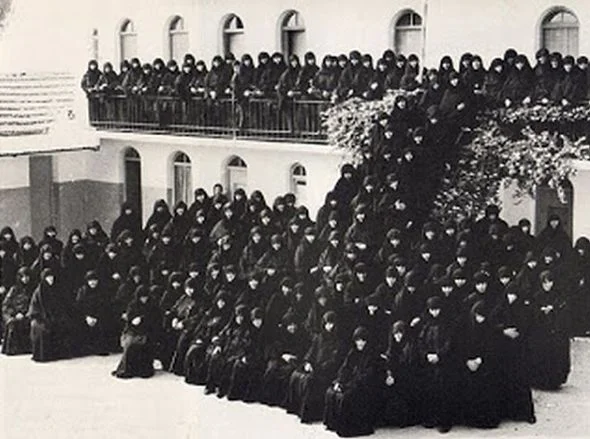

Karpathakis, already in his sixties and in poor health, devoted himself to fasting and solitary prayer. Administration of the convent fell increasingly to Soulakiotis, who by the early 1930s held the title Mother Mariam of Keratea. The convent expanded rapidly, adding dormitories, a refectory, and farm buildings financed through public donations.

Initially promoted as a retreat for women seeking religious life, the monastery soon attracted another group: tuberculosis patients. At the time, the disease was widespread in Greece, and treatment options were limited. The monastery’s mountain location, believed to offer “curative air,” made it an appealing refuge. Patients arrived seeking rest, food, and faith-based healing.

By the end of the decade, the monastery housed nuns, invalids, and lay followers. Soulakiotis controlled all daily operations finances, admissions, and discipline while Archbishop Matthew spent long periods in isolation, weakened by illness and prolonged fasting. When he died in the late 1930s, leadership passed entirely to her.

From that point, the convent’s structure changed. Rules grew stricter, penance harsher, and all property belonging to members or residents was registered under the monastery’s name. The organization that had begun as a religious refuge now operated as a closed community governed solely by the abbess.

The Monastery of Asceticism

By the early 1940s, the Convent of the Virgin in the Pines had become one of the most active centers of the Old Calendarist movement. Officially, it was registered as a charitable religious institution devoted to prayer, fasting, and care for the sick. Unofficially, it operated under a set of internal rules known only to its members.

Admission and Discipline

New entrants both nuns and lay followers were required to surrender their personal belongings and sign documents declaring that their property “belonged to God through the monastery.” Witness testimony later confirmed that many of these transfers were recorded under Mariam Soulakiotis’s personal name, not the convent’s.

Newcomers underwent what was described as a forty-day fast and period of silence. Former residents later told investigators that these fasts were enforced through isolation. Individuals were confined to small rooms or underground cells, fed minimal portions, and denied sleep as part of “spiritual cleansing.” Those who attempted to leave were restrained or punished.

Doctors from nearby Keratea later reported that they were rarely allowed inside the monastery. Their visits were limited to signing death certificates, often for patients registered as tuberculosis victims. No medical equipment or supplies were found on the premises during the 1950 search.

Treatment of the Sick

During this period, tuberculosis remained one of Greece’s most common fatal diseases. The monastery promoted itself as a sanatorium, promising fresh air and prayer-based healing. Families sent relatives there hoping for recovery. Many never returned.

Police records list multiple cases of death by starvation or neglect, including that of a woman known as Mrs. Michalakou, who arrived as a tuberculosis patient and was confined until she died. Several others were documented as having “expired under ascetic practice.”

Punishment of Dissent

The abbess’s authority extended to the nuns themselves. Those who questioned her methods faced internal discipline. One nun, Sister Theodote, was beaten by order of the abbess after speaking out against the confinement of the sick. She died from internal hemorrhage. Another, Sister Maria, suffered severe injuries during punishment and later died in a hospital in Athens.

Financial Expansion

Under Soulakiotis’s control, the monastery acquired dozens of new properties. Title deeds show that families who joined the order often widows and childless women donated land and homes as acts of devotion. Some transfers were made under duress. In one documented case, a couple identified as Mr. and Mrs. Baka were held in isolation until they signed over their assets. Both died shortly after.

By the end of the decade, the monastery owned farms, urban properties, and rental houses throughout Attica and the Peloponnese. Revenue from these holdings funded construction projects and supported missionary travel across Greece, where emissaries recruited more followers.

Public Silence

Villagers who lived near the monastery later told police they occasionally heard shouting or saw elderly residents working under guard. None reported it at the time. To outsiders, the convent remained a place of piety. To those inside, it was a closed world governed entirely by the abbess, where obedience was absolute and suffering was interpreted as salvation.

Faith and Fear

By the late 1940s, the monastery’s reputation had begun to fracture. Families of former residents questioned the circumstances of their relatives’ deaths. Property transfers in favor of the convent appeared in notarial records across Athens and Attica, often made by elderly or infirm individuals shortly before they disappeared from public view.

In 1948, a woman contacted the authorities, reporting that her mother had transferred her entire estate to the monastery. The daughter claimed the decision had been coerced. Around the same time, another former resident, Eugenia Margetti, came forward with detailed allegations. She stated that she had been detained in isolation and tortured until she signed over property valued at 118 million drachmas equivalent to tens of thousands of U.S. dollars at the time.

These accounts led police to begin monitoring the monastery’s finances. Investigators discovered that the abbess was involved in an illegal import business, moving olive oil, tires, and other goods through the convent’s trade network without authorization. Though minor compared to the accusations of abuse, the smuggling charges provided a legal basis for a search warrant.

In 1949, international attention forced the case wider. A Greek expatriate living in the United States, Christos Spyrides, reported his eighteen-year-old daughter missing. She had last been seen at the Keratea convent after being persuaded to join by one of its nuns. With the help of U.S. authorities, Greek police traced her movements and confirmed she had stayed at the monastery. She was later found alive and reunited with her father.

The Spyrides case turned private suspicion into a national issue. Greek newspapers began publishing reports of women disappearing into the convent and families losing their property. Former residents described fasting, confinement, and forced “penance.” A few spoke of deaths by starvation and illness.

By the time investigators secured the warrant for the December 1950 raid, the case file included allegations of unlawful detention, embezzlement, and homicide. Witness lists named both surviving victims and relatives of the dead. Property registries documented nearly 300 holdings in the abbess’s name.

Contemporary press coverage most notably reports from Reuters and the Associated Press described the monastery as possessing gold, jewelry, and currency worth thousands of pounds. Internal estimates by the Ministry of Justice placed the number of deaths linked to the convent at between 27 and 150, depending on classification of starvation and neglect.

Despite the mounting evidence, Mariam Soulakiotis continued to present herself as a servant of faith. In her communications with church sympathizers, she insisted the accusations were “attacks by the unfaithful” and claimed that those who died had simply “fulfilled their vows through suffering.”

The investigation concluded with the formal decision to arrest her. On December 4, 1950, at dawn, the police entered the monastery for the search that would expose the full extent of her operations.

Trial and Aftermath

Following the December 1950 raid, Abbess Mariam Soulakiotis and several senior nuns were taken into custody. The initial indictment concerned illegal importation and trade of olive oil and tires, the charges that had first justified the search. The case quickly expanded as investigators compiled evidence of fraud, forgery of wills, extortion, and negligent homicide.

The First Trial (1951–1952)

The first proceedings opened in Athens in 1951. The prosecution focused on the smuggling offenses, a charge that was easiest to prove. Testimony from financial auditors confirmed unlicensed imports and irregular transactions amounting to significant profits. Soulakiotis was found guilty and sentenced to twenty-six months in prison.

Although the conviction covered only the commercial aspects of the monastery’s operations, press coverage of the trial generated a wave of new complaints. Families of the deceased came forward describing coercion and starvation inside the convent.

The Second Trial (1953)

A broader investigation led to a second trial held in 1953. The charges now included homicide by neglect, physical abuse, fraud, and embezzlement. Over forty witnesses testified, including surviving nuns, villagers, and relatives of victims. The prosecution documented at least twenty-seven deaths, while internal estimates by investigators suggested the figure could be as high as one hundred seventy-seven.

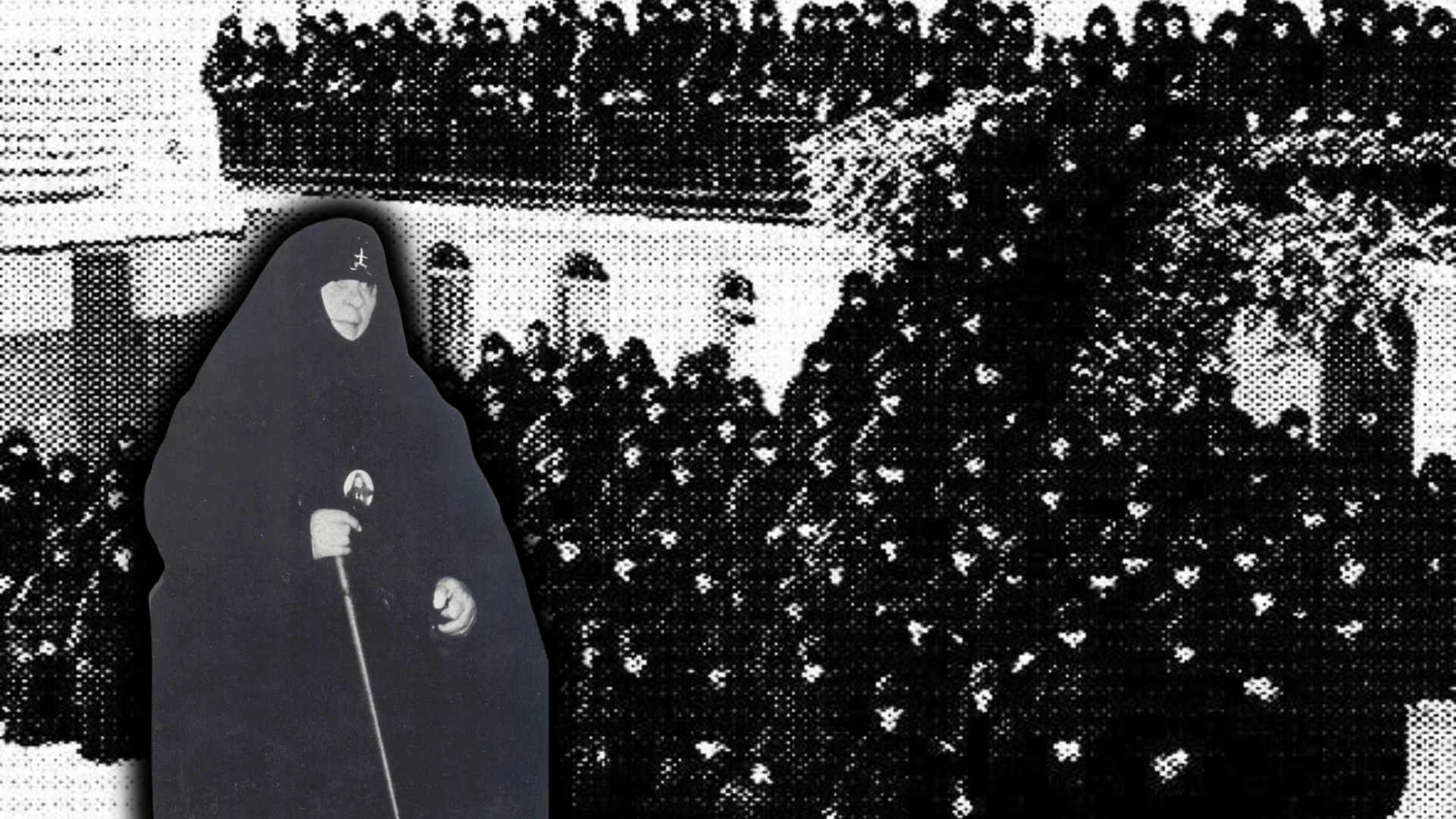

During the hearings, Soulakiotis denied all accusations. She appeared in court wearing full religious habit and an icon of Archbishop Matthew pinned to her chest, addressing the judges as “servants of the devil.” Her defense attorney argued that all residents of the monastery had voluntarily taken vows of poverty and that the transfer of property had been legally valid.

The court rejected the defense’s argument. Soulakiotis was convicted on multiple counts and sentenced to ten years in prison.

The Third Trial (1954)

A third and final proceeding followed shortly afterward, adding four more years for illegal detention. The total sentence amounted to fourteen years.

By that time, the Old Calendarist community known as the Matthewites had been declared illegal by the Greek government. Despite this, followers of Soulakiotis held public demonstrations demanding her release and veneration as a saint. Police placed the Archbishop of Athens under protection amid rumors of a planned abduction by the sect.

Imprisonment and Death

Soulakiotis served her sentence at Averof Prison in Athens. Records show she remained in custody for roughly one year before being transferred to a hospital due to declining health. She died in 1954, aged 71, still maintaining her innocence.

After her death, more than 400 followers continued to operate small prayer groups across Greece. Many regarded her as a martyr persecuted for her faith. To others, she remained responsible for one of the largest series of deaths ever linked to a religious institution in the country.

Legacy

By the time the final report was closed, authorities had documented dozens of verified deaths, hundreds of coerced property transfers, and the rescue of thirty-six children. The monastery’s assets were seized and later redistributed by the state.

The building still stands above Keratea, surrounded by pine trees and farmland. Its chapel remains intact but unused, its bell tower silent.

Epilogue

The case of Mariam Soulakiotis the nun the press later called Mother Rasputin remains one of the most complex intersections of faith and crime in modern Greek history.

Between 1927 and 1950, her monastery functioned as both a religious sanctuary and a closed system of control. Its decline exposed how devotion, isolation, and unchecked authority could coexist beneath the language of piety.

The official investigation closed in 1955, listing property seizures valued at several million drachmas and confirming deaths attributed to starvation, disease, and assault. No exact number was ever established. The files in the Hellenic Ministry of Justice record only the phrase “multiple victims under prolonged neglect.”

In the decades that followed, the Old Calendarist movement splintered but survived. Within some branches, Soulakiotis was quietly revered as a misunderstood ascetic. Others erased her name entirely from their records. For most Greeks, the story became a cautionary legend how an institution built to serve the devout could turn into a place of suffering hidden in plain sight.

The monastery still stands on the hill above Keratea, its white walls partly restored. The pine forest has grown thick around it, and the road that once carried trucks of police is now used by hikers. No sign marks the site’s history. Locals say the air there is quiet, and the only sound that remains is the wind moving through the trees.