On August 2, 2006, attorney Robert Wone left his office in Washington, D.C., and headed to a friend’s townhouse on Swann Street for the night. It was supposed to be a simple overnight stay, but within ninety minutes he was found fatally stabbed in the guest room.

The scene was disturbingly calm little blood, a knife placed neatly on a nightstand, and three housemates claiming an intruder had slipped in and vanished.

A Night on Swan Street

Robert Eric Wone, a 32-year-old attorney from Oakton, Virginia, had built a reputation as a hardworking and meticulous professional. He was the general counsel at Radio Free Asia, a nonprofit news organization in Washington, D.C., and lived in Oakton with his wife, Katherine Wone.

On August 2, 2006, Robert planned a late night of work and chose to stay overnight in the city rather than drive home. He arranged to spend the night at the 1509 Swann Street NW townhouse, owned by his college friend Joseph Price, a prominent lawyer.

Price lived there with his partner Victor Zaborski and their close friend Dylan Ward. The three men shared the four-story townhouse, known among friends as a secure, upscale property in Dupont Circle.

Robert finished his work at Radio Free Asia and arrived at the Swann Street home shortly after 10:30 p.m. According to records, this was his first visit to the townhouse. Price offered Robert the guest room on the second floor, where a pullout sofa bed had been prepared for him.

By 10:45 p.m., the household seemed quiet. Price, Zaborski, and Ward claimed they prepared for bed around this time, while Robert showered and changed into a gray T-shirt and shorts. Less than ninety minutes later, he would be dead.

The 911 Call

At 11:49 p.m. on August 2, 2006, a calm yet urgent 911 call came from the third floor of 1509 Swann Street NW. The caller, Victor Zaborski, reported that “an intruder” had entered the home and stabbed their guest, Robert Wone. His voice trembled slightly, but he spoke clearly, providing the address and stating Robert was still breathing.

Paramedics arrived at the scene around 11:54 p.m., followed closely by the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD). They expected chaos, but instead entered a silent, tidy home.

Robert was discovered in the second-floor guest room, lying on the pullout sofa bed. He was dressed in a gray T-shirt and gym shorts, his body positioned neatly, as if placed there intentionally. The bed was clean, with barely any visible blood despite three stab wounds in his torso.

Next to the bed sat a kitchen knife, positioned neatly on a small nightstand. Later forensic analysis would reveal that this knife was unlikely the murder weapon.

The three housemates Joseph Price, Victor Zaborski, and Dylan Ward stood nearby. Zaborski appeared tearful but composed, Price remained unusually calm, and Ward stayed mostly silent and withdrawn. None showed signs of panic or urgency.

As first responders worked to stabilize Robert, they noticed something troubling. Despite the severity of his injuries, there was very little blood. His wounds appeared precise and deep, but not chaotic. It didn’t resemble the aftermath of a typical violent struggle.

Paramedics rushed Robert to George Washington University Hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 12:24 a.m. on August 3, 2006.

Meanwhile, officers secured the house. They immediately noticed no signs of forced entry no broken locks, no shattered windows, no tampered doors. Valuables in plain sight remained untouched. Price told police he had seen “a black man running through the alley,” a detail that investigators would later question heavily.

Within the first hour, detectives suspected something deeper was wrong.

Inside the Crime Scene

When investigators began examining 1509 Swann Street, they expected to find signs of a violent break-in or chaotic struggle. Instead, the townhouse looked undisturbed.

The front door showed no damage, locks were intact, and windows were secure. Drawers, shelves, and valuables remained untouched.

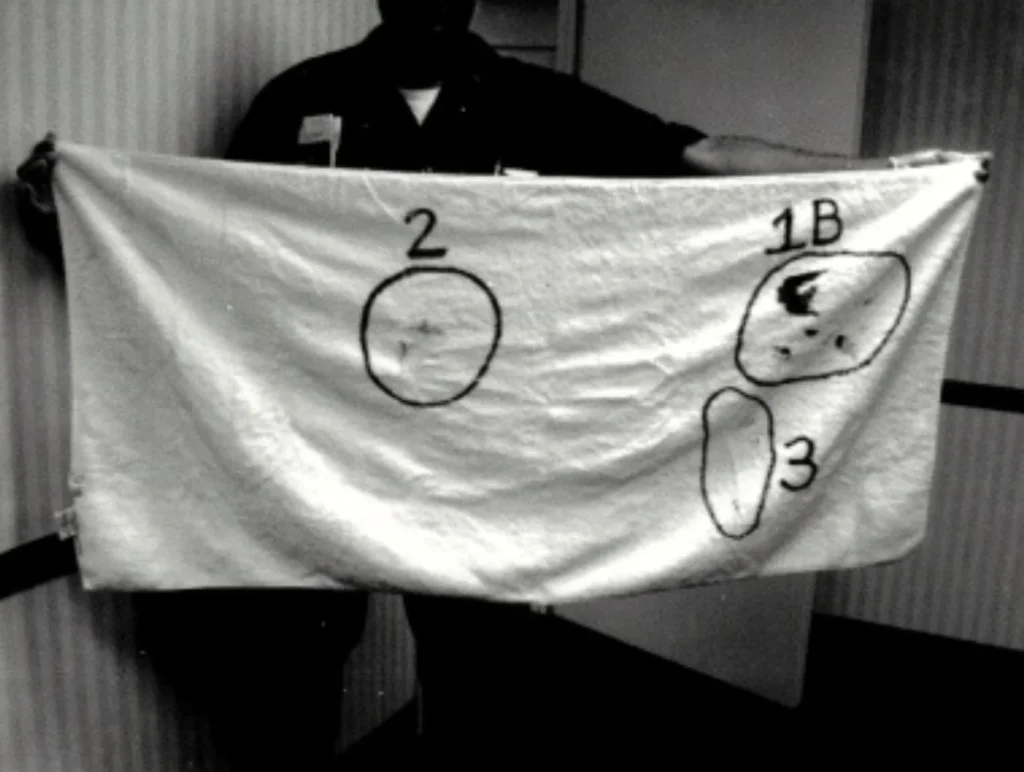

Inside the second-floor guest room, where Robert Wone had been found, investigators made several puzzling observations. The bed was neatly arranged, almost as if prepared for a guest earlier in the evening. Despite Robert’s three deep stab wounds, there was very little visible blood on the bedding or floor.

A kitchen knife rested neatly on the bedside table. At first glance, it seemed to be the weapon, but the blade didn’t match Robert’s wounds. One knife from Dylan Ward’s personal cutlery set was missing, and its size and shape matched the stab wounds perfectly. It has never been recovered.

Further complicating the scene, detectives noticed a blood-stained towel near the washer and dryer in the basement. Forensic analysis revealed fibers from the towel matched the blade, but no fibers from Robert’s shirt were found on the knife itself suggesting the shirt may have been removed or changed before the stabbing or immediately afterward.

Police brought in cadaver dogs, which alerted strongly at the clothes dryer’s lint trap and the backyard drain. Investigators suspected that items possibly bedding, clothing, or even the real weapon may have been washed or disposed of during the critical minutes before the 911 call.

Even more alarming were items recovered from Dylan Ward’s bedroom. Detectives found manuals on bondage and sadomasochism, restraints, and equipment suggesting possible sexual activity. While prosecutors never claimed Robert was definitively assaulted, the discovery deepened suspicion that something far more complex happened that night.

Despite hours at the scene, police found no evidence of an intruder no footprints, no foreign DNA, no disturbed entry points. Instead, all clues pointed inward, raising the unsettling possibility that someone inside the house knew more than they admitted.

The Autopsy and Forensics

On the morning of August 3, 2006, the D.C. Medical Examiner performed Robert Wone’s autopsy. Instead of resolving the case, the findings only made it stranger.

Robert had three deliberate stab wounds, including one straight to the heart. The cuts were precise, not frenzied, and his body showed no defensive injuries. For an athletic 32-year-old, the absence of resistance suggested he had been unconscious or immobilized when attacked.

Medical examiners also found needle marks on his neck, chest, hand, and foot. Paramedics confirmed they hadn’t given injections in those areas. Toxicology came back negative for alcohol or sedatives, but investigators pointed out that certain paralytics, like succinylcholine, weren’t part of standard testing at the time. That raised the possibility Robert had been chemically incapacitated.

Seminal fluid was detected on his body. There were no signs of forced assault, but combined with restraints and sexual devices found in Dylan Ward’s room, the discovery deepened suspicion that Robert had been subdued in some way.

Taken together, the autopsy and crime scene told a disturbing story: no struggle, almost no blood, a staged knife on the nightstand. Within 90 minutes of arriving at the townhouse, Robert had gone from guest to victim, in a death that looked anything but random.

The Investigation Intensifies

By September, detectives had dropped the intruder theory. Nothing in the house supported it no broken locks, no missing valuables, no footprints or foreign DNA. The focus shifted entirely to Price, Zaborski, and Ward.

When interrogated separately, the three men gave nearly identical accounts. That precision was unusual; truthful witnesses almost never remember events word for word. Price repeated the intruder story but turned evasive when asked about specifics. Zaborski, frantic in his 911 call, appeared calm and detached in person. Ward barely spoke, and when he tried to, Price cut him off. Detectives saw this as a sign of coordination.

The physical evidence only made the men look worse. The knife didn’t match the wounds, blood in the room didn’t fit the expected patterns, and cadaver dogs had alerted to the dryer and the backyard drain, suggesting something had been cleaned or disposed of before help was called.

Investigators began to suspect Robert was restrained, chemically subdued, and then stabbed, with the scene staged afterward. But suspicion wasn’t proof. Without DNA, fingerprints, or eyewitness testimony, a murder charge wasn’t possible.

The Criminal Trial and Acquittal

With no direct evidence, prosecutors took another path. In October 2008, the three housemates were charged not with murder but with obstruction of justice, conspiracy, and tampering with evidence. The case argued that they had staged the crime scene, delayed the 911 call, and misled investigators.

The trial opened in May 2010 before Judge Lynn Leibovitz. Prosecutors laid out their theory: Robert had been incapacitated, possibly restrained, then stabbed, with the scene made to look like an intruder attack. They pointed to the needle marks, the lack of blood, and the improbably clean room.

The defense hit back hard. They argued that the men’s statements matched because they lived together and remembered events similarly. They said the intruder theory, while unlikely, couldn’t be entirely ruled out.

Over several weeks, more than 80 witnesses testified paramedics, forensic experts, detectives, neighbors. The government built a case heavy on suspicion but light on proof. In the end, that wasn’t enough.

On June 29, 2010, Judge Leibovitz acquitted all three defendants. She called their accounts “highly implausible” and said it was “very probable the defendants know more than they are saying.” But probability, she reminded the court, is not proof.

The Civil Lawsuit and Settlement

For Robert’s widow, Kathy Wone, the acquittal was devastating. She had already filed a wrongful death lawsuit in 2008 against Price, Zaborski, and Ward, alleging they knew far more than they admitted.

Civil court required only that it be more likely than not that the men concealed or contributed to Robert’s death. The case drew out details hidden in the criminal trial. Attorneys emphasized the needle marks, missing knife, and evidence of staging. When questioned, the defendants invoked the Fifth Amendment again and again.

With reputations and finances at stake, the pressure grew. In August 2011, just before the trial was set to begin, the parties reached a confidential settlement. The terms were never disclosed, and the defendants admitted no wrongdoing.

Even so, the lawsuit left behind a thick public record: depositions, filings, and investigative reports that laid bare the contradictions. Yet the central question who killed Robert Wone remained unanswered.

Theories and Unanswered Questions

Nearly every theory has been considered, and none fully explain the facts.

The intruder story was the housemates’ defense from the start, but with no forced entry, no stolen valuables, and no trace of anyone else, police dismissed it.

Some have suggested accidental death during sexual activity, with panic leading to a cover-up. Friends of Robert reject this idea, describing him as private, committed to his marriage, and not the type to engage in risky experimentation.

The chemical incapacitation theory carries weight. Needle marks with no medical explanation, no defensive wounds, and clean, precise stabs all fit with the use of a paralytic drug that wasn’t tested for in 2006.

The possibility of a sexual element lingers too. Semen was found, restraints and manuals were discovered in Ward’s room, but no charges of assault were ever filed. Whether these details connect to Robert’s death or not is still unknown.

The most widely accepted theory among investigators is that the three men coordinated a cover-up. Their stories matched too closely, the crime scene appeared staged, and evidence may have been destroyed in those crucial minutes before the 911 call. Judge Leibovitz herself said it was likely they knew more. Still, without direct forensic proof, prosecutors could not pursue murder charges.

Aftermath

After the acquittal, Price, Zaborski, and Ward withdrew from public life. The Swann Street townhouse was eventually sold in 2019. Price moved to Florida and resumed practicing law. Zaborski and Ward relocated to Miami, where they opened a business together. None of the three has spoken publicly about the case.

Kathy Wone, meanwhile, turned her grief into advocacy. She co-founded the Robert E. Wone Foundation for Justice, which supports forensic science improvements and pushes for better methods to detect chemical incapacitation and staged crime scenes.

The case remains open with D.C. police. For years, detectives have re-tested evidence and re-interviewed witnesses, but no new leads have emerged.

Media coverage has kept the case alive from Dateline NBC to true-crime podcasts and documentaries. It has become a symbol of how much can go wrong when evidence is ambiguous or destroyed, and when suspicion outweighs proof.

Judge Leibovitz’s words from 2010 still define it: “It is very probable the defendants know more than they are saying. But probability is not proof.”

Nearly two decades later, the murder of Robert Wone remains unsolved a locked house, three witnesses, and no answers.