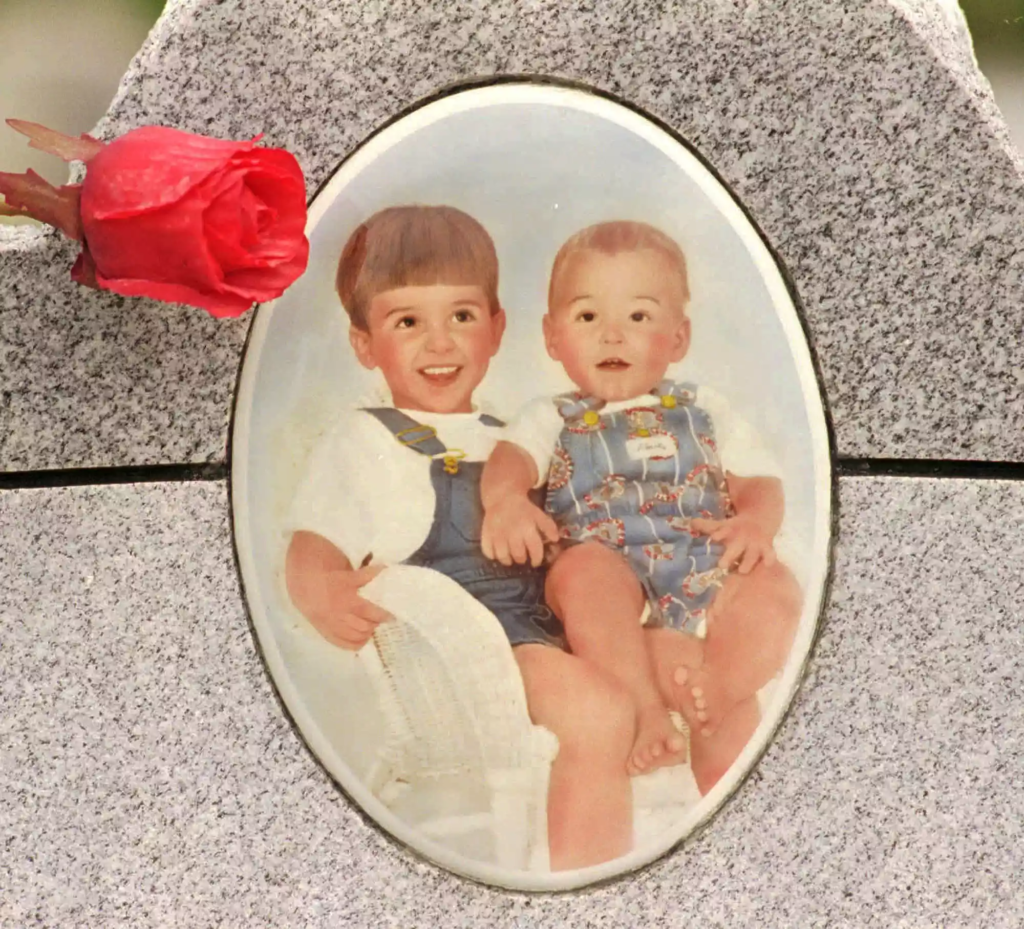

On the night of October 25, 1994, Susan Smith released her Mazda into John D. Long Lake with her sons Michael, 3, and Alex, 14 months, still strapped in their car seats, then spent nine days weeping on national television blaming a Black carjacker for their disappearance.

Just after 9:00 p.m. on October 25, 1994, Susan Smith parked her red Mazda at the edge of a boat ramp on the quiet shore of John D. Long Lake, outside Union, South Carolina. Her two sons, Michael, 3 years old, and Alex, 14 months, sat strapped in their car seats in the back. Michael looked out at the dark water and asked his mother a question.

Mommy, where are we going? Susan did not answer. She shifted the car into neutral and let it roll forward. She stopped. She tried again. She stopped again. On the third attempt, she stepped outside, reached back in, and released the brake for the last time.

The car rolled into the water and disappeared beneath the surface, settling 122 feet from the bank in 18 feet of water. Then Susan Smith walked away. She crossed to Highway 49, ran approximately 100 yards to a nearby home with its porch lights on, and knocked on the door. When a resident answered, Susan told him that a Black man with a gun had stolen her car at a red light. Her children, she said, were still inside.

The Nation Watched

Within minutes, police were on the scene. By the following morning, the story had reached every television set in America. Two small boys, a 3-year-old and a 14-month-old still in their car seats, taken at gunpoint from their mother at a traffic light in Union, South Carolina. The image was designed to produce maximum horror, and it did.

For nine days, Susan Smith stood before cameras and pleaded. “I can’t express how much they are wanting back home,” she told reporters, her voice breaking. Beside her stood David Smith, 24, the boys’ father and legally her ex-husband, though few in the watching nation knew that yet. He appeared shell-shocked, his expression rigid.

They had been divorced for five months. They appeared as a couple. Roadblocks went up. Amber Alerts were issued. Flyers bearing Michael and Alex’s faces appeared in every storefront and gas station in Union County. Volunteers scoured rural roads and wooded areas. Helicopters swept highways. The FBI joined the search. Porch lights burned across Union in solidarity.

Nothing turned up. No sightings of the red Mazda. No witnesses to any carjacking. No tire marks, no signs of struggle, nothing.

Cracks Appeared

While the search played out on national television, detectives in Union were reaching private conclusions. Susan’s demeanor was wrong in ways that were difficult to name but impossible to ignore. She would sob through press conferences, then turn girlish and almost giddy the moment cameras were off. One detective noted her expression while waiting for a television interview to begin: wide-eyed, flushed, almost excited. The moment the cameras rolled, the grief returned on cue.

She asked no questions about the search. Parents of missing children typically demanded constant updates: had police checked new areas, had any leads developed, what was being done? Susan waited to be approached. In private moments, when she believed no one was watching, she laughed and chatted with the ease of someone who had set down a burden.

Then there were the mechanics of her story. She claimed a carjacker had forced her to drive for nearly an hour before stopping her on a rural road. Retracing her route produced no witnesses, no security footage, and no timeline that held together.

The traffic light on Monarch Mills Road where the supposed abduction occurred was controlled by sensors: it would only turn red if cross-traffic triggered it. There had been no cross-traffic. And there was one detail Susan had not anticipated: undercover officers had been stationed at that intersection on the night of October 25th, running a separate drug investigation.

They saw no carjacking. They saw no woman forced from her car. They saw nothing.

By day three, detectives had quietly shifted their focus. They were no longer searching for a carjacker.

The Confession

Over the following days, investigators brought Susan back repeatedly, asking her to retell her story in careful detail. Each retelling shifted. The duration of the forced drive changed. The direction she had been facing at the intersection changed. She claimed to have struggled when the man pushed her from the car, yet there were no injuries on her body and no physical evidence at the location she described. She submitted to two polygraph examinations.

She failed both.

On November 3, 1994, nine days after Michael and Alex were last seen alive, Sheriff Howard Wells, who also happened to be Susan’s godfather, sat across from her and told her directly that he knew she was lying. He walked through each inconsistency. He told her about the officers who had been stationed at the intersection. He told her the false accusation had generated racial tension in a town with a complicated history, and the lie could not stand.

Susan asked him to pray with her. When the prayer ended, Wells looked at her and said: Susan, it is time.

She dropped her head and began to sob. Then she asked him for his gun.

When he asked why, she said: You don’t understand. My children are not all right.

Her written confession ran two pages, composed in rounded script. She drew small hearts wherever she wrote the word “heart.” She described parking at John D. Long Lake, shifting the car into neutral, stopping herself twice, stepping outside, and releasing the brake a final time. “I had no hope,” she wrote. “I couldn’t be a good mom anymore.” She wrote that her sons would be better off with God than left behind without a mother. “My children Michael and Alex are with our Heavenly Father now, and I know that they will never be hurt again. As a mom, that means more than words could ever say.”

Divers located the Mazda that afternoon using sonar — resting 18 feet below the surface of John D. Long Lake, 122 feet from shore. Michael and Alex were still strapped into their car seats. The car doors were locked.

Tom Finley’s Letter

Susan’s motive, when investigators pressed her, was a letter. To understand the letter, it is necessary to understand what Susan Smith’s life had become by the fall of 1994.

She was born Susan Leigh Vaughan on September 26, 1971, in Union. When she was 6 years old, her father Harry Vaughan died by suicide. Her mother Linda later married Beverly Russell, a local businessman with ties to the Christian Coalition. Susan reported — and Beverly eventually admitted, that he had sexually abused her throughout her adolescence, continuing well past the time she became an adult.

After high school, Susan took a job at Conso Products, a textile company in Union. She met David Smith there and they married in March 1991, when she was 19. The marriage was unstable from the start: mutual infidelity, financial strain, repeated separations. They had two sons together (Michael in 1991, Alex in 1993) and officially divorced in May 1994. They were appearing jointly in front of cameras as a grieving couple while legally estranged.

After the divorce, Susan began a relationship with Tom Finley, the son of her boss at Conso, a man from a well-established local family with the kind of money and social position Susan had long sought. She was also, by her own later admission, sleeping with Tom’s father. Tom learned of this.

The letter he wrote to end the relationship was later entered into evidence at trial. Among its contents: “I could really fall for you, but like I told you, some things are not suited for me. I am talking about the children. I do not want children and I don’t want the responsibility of your children either.” His final line to her: “You have to make your own decisions in life, but remember you have to live with the consequences of those decisions.”

In her confession, Susan wrote: “I was in love with someone very much, but he didn’t love me and never would.”

The Media Spectacle

Susan’s trial opened on July 10, 1995, running simultaneously with the O.J. Simpson proceedings that were consuming the rest of the country’s attention. News outlets rented storefronts for the duration. Scaffolding was erected for camera crews along the street leading to the courthouse. A local skating rink was converted into temporary housing for journalists. Reporters hid in trees and behind bushes.

The prosecution sought the death penalty, arguing premeditation: Susan’s fixation on Tom Finley, her calculation that the children were the obstacle between her and the life she wanted. Forensic experts testified that Michael and Alex were alive when the car entered the water.

The prosecution played a video reenactment of the car sinking. When the footage was previewed in a sidebar exchange with attorneys, Susan and a paralegal were observed laughing. When the same video was played for the jury, Susan was weeping. The jury saw both versions of that reaction, and had already spent weeks watching the woman who wept in front of cameras while her children lay at the bottom of a lake.

Beverly Russell took the stand and admitted his abuse of Susan, both during her childhood and beyond. He wrote her a letter outside the courtroom: “I want to tell you how sorry I am for letting you down as a father. Many believe my failure didn’t have anything to do with October 25th, but I believe it did.” The prosecution argued that Russell’s appearance was an attempt to redistribute moral responsibility. A defense psychiatrist testified that Susan suffered from chronic depression and adjustment disorder, and asked the jury to weigh life in prison against death.

After two and a half hours of deliberation, the jury found Susan Smith guilty on both counts of murder. They sentenced her to life in prison. What the jury was not permitted to know, and explicitly asked the judge about before he redirected them to take a life sentence at its “plain and usual meaning,” was that under the law at the time of sentencing, life in prison carried parole eligibility after 30 years. The following year, South Carolina changed the law to allow juries to be informed of that fact.

Behind Bars

Incarceration did not alter the pattern. In 2000, it was discovered that Susan had been involved with a prison guard, who subsequently served three months in jail. Later, she cultivated a relationship with Captain Alfred Rowe Jr., the head of security at the facility. According to Rowe, Susan would chat with him regularly, flirt, and expose herself when passing him after showers. She also informed on other inmates to gain proximity.

Their eventual encounter resulted in Rowe’s arrest, termination, five years’ probation, and permanent placement on the national sex offender registry, where his name will remain for the rest of his life. His marriage survived. He has been unable to find steady work since. He believes Susan reported him deliberately, to manufacture cause for a transfer to Leath Correctional Institution, closer to her mother. The transfer was granted.

A former cellmate named Christy, who had served as Susan’s lookout during various encounters and helped her obtain drugs, described the financial economy Susan operated within. Money moved through Susan’s prison account in substantial quantities: from admirers, from men she cultivated through correspondence, from strangers.

One man planned to give her more than $200,000 upon her release. Another corresponded with her for 18 months before discovering she was writing to others simultaneously. He described feeling used.

During an argument between Susan and one of her prison companions, Christy overheard Susan tell the woman: I killed my kids. Do you think I care about yours?

The Parole Hearing

In November 2024, thirty years after Michael and Alex Smith were carried to the bottom of John D. Long Lake, Susan Smith appeared before the South Carolina parole board. She wept throughout. She pressed tissues to her eyes, spoke of God’s forgiveness, and said she was sorry. She said she was really, really sorry. She told the board that God had forgiven her, and asked them to show the same mercy.

David Smith attended. He reminded the board that his sons’ deaths were not a tragic accident. They were a deliberate act.

The board denied parole unanimously. Her next hearing is scheduled for November 2026.

The performance Susan gave that morning was distinctive for one reason: it was familiar. The tissue pressed repeatedly against dry eyes. The emotion calibrated precisely to the room. Anyone who had watched the nine days of 1994 press conferences would have recognized it immediately. Thirty years had passed. The presentation had not changed.

In a quiet moment during her final interrogation before her confession, an investigator asked Susan Smith: if she could have one wish, what would it be? She did not wish she had never driven to that lake. She did not wish Michael and Alex were still alive. She said she wished she had never told Tom Finley about her affair with his father.

In the back seat of that car, at the edge of the dark water, 3-year-old Michael had looked out and asked his mother where they were going.

She never answered him.