In 1930, a hospital technician in Key West began treating a 22-year-old tuberculosis patient named Maria Elena de Hoyos. After her death the following year, he continued visiting her mausoleum and later removed her remains without the family’s knowledge.

Over the next several years, he kept the body in his home and attempted various preservation and reconstruction methods until the case was discovered in 1940.

Early Life

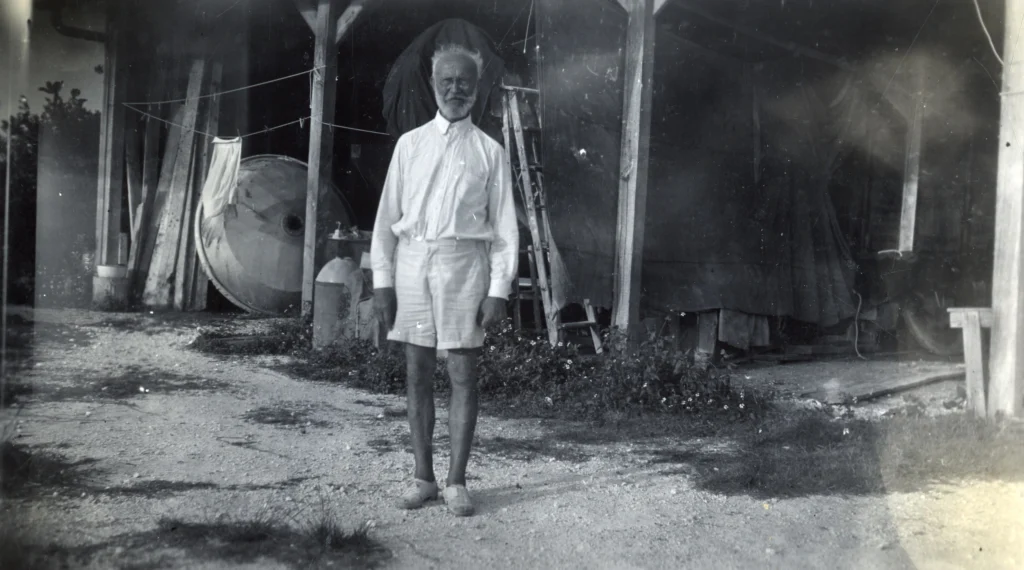

Carl Tanzler was born in 1877 in Dresden, Germany, where he grew up with his sister. From childhood, he immersed himself in electricity, chemical experiments, astronomy, flying machines, and what he called “all phenomena of the universe.” While still in school, he built his own glider.

He later studied multiple disciplines at university. In his autobiography, he claimed he took final degrees in medicine, philosophy, mathematics, physics, and chemistry by age 24. None of these credentials qualified him as a medical doctor, but he portrayed himself as one throughout his life.

Before World War I, Tanzler traveled widely. He left Germany for India, then journeyed from India to Sydney, Australia. In Sydney, he worked for the government as a civil electrical engineer and an X-ray expert. He spent nearly ten years there and had begun constructing a trans-ocean aircraft when the war halted his plans.

When World War I broke out in 1914, British authorities classified him as an enemy national and placed him in a concentration camp. He remained interned until the war ended in 1918. Former prisoners were not permitted to stay in Australia afterward, so he was deported to Holland.

From Holland, he searched for his mother, whom he had not heard from since the start of the war. He returned to Germany, found her, and stayed with her for two years. In 1920, he married Doris Schaefer. The couple had two daughters: Aisha and Clarista.

Immigration to the United States

In 1926, Tanzler left Germany with his wife, Doris, and their daughters, Aisha and Clarista. The family sailed to Florida and settled in Zephyrhills, where his sister was already living. On paper, he was still listed under the name Carl Tanzler von Kossel, one of several identities he used throughout his life.

He lived with his family for less than a year. By 1927, he abruptly abandoned them and moved alone to Key West. He never explained the decision, and he left Doris to raise their children without support. Although they later reestablished contact, they never resumed their marriage.

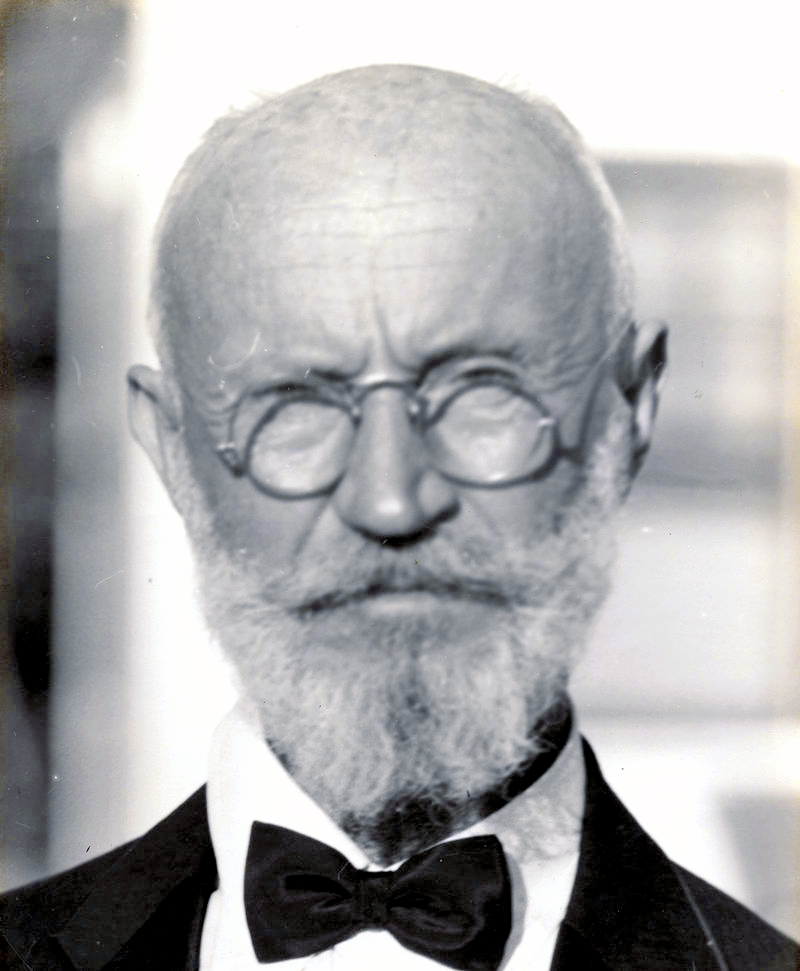

After relocating, Tanzler secured work at the U.S. Marine Hospital in Key West. He introduced himself as Count Carl von Cosel, adopting a title he had no legal claim to. At the hospital, he worked in the tuberculosis ward as an X-ray technician and presented himself as a radiologist, despite having no recognized medical qualifications.

He exaggerated his academic background, frequently implying he was a trained doctor. Coworkers described him as arrogant, theatrical, and obsessed with portraying himself as a scientific authority. In a ward where no cure for tuberculosis existed, he often claimed he had discovered one. He never demonstrated such a cure, but he spoke as if he possessed secret knowledge others lacked.

By the time he met his future victim, Tanzler had already crafted a mythic version of himself noble title, scientific genius, and imagined expertise far removed from his actual training and experience.

Meeting Maria Elena “Helen” Milagro de Hoyos

On 22 April 1930, 22-year-old Maria Elena Milagro de Hoyos arrived at the U.S. Marine Hospital in Key West. Her family brought her in after she became seriously ill with tuberculosis. The disease had no cure, and most cases at the time were fatal.

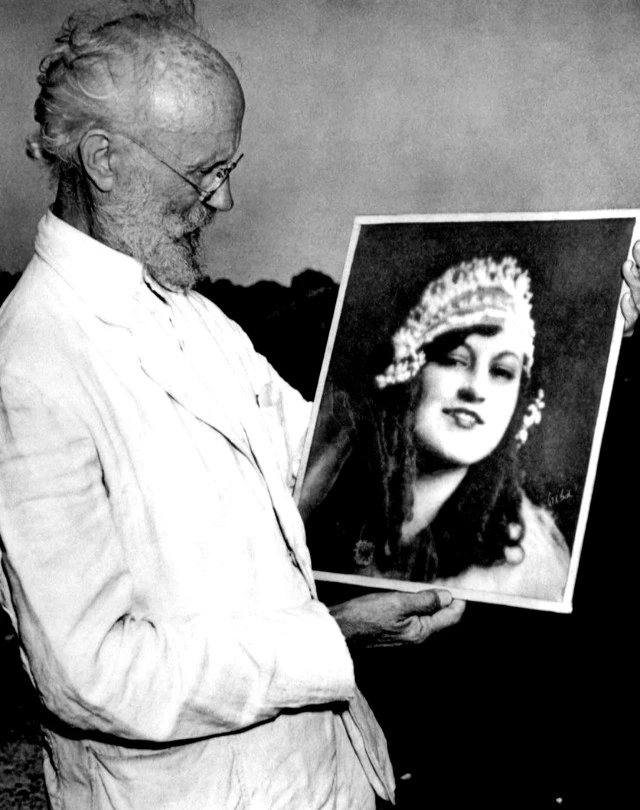

Tanzler, age 55, was working in the tuberculosis ward when he first saw her. He later wrote that he became “enamored instantly,” believing she matched a woman he had seen in a series of visions as a boy in Germany. In those visions, he claimed an ancestor Countess Anna Constantia von Cosel appeared to him and showed him an “exotic, dark-haired woman” who would be his destined love. Tanzler insisted Helen was that woman.

Helen was born in Key West in 1909. She was Cuban American, the daughter of Francisco, “Pancho” Hoyosa cigar maker, and Aurora Milagro, a homemaker. She grew up with two sisters, Florinda (known as Nana) and Celia.

In 1926 she had married Luis Mesa, but after she suffered a miscarriage he abandoned her and moved to Miami. They were still legally married when she met Tanzler.

Tanzler interpreted Helen’s beauty and politeness as affection. Her family later said she never expressed interest in him. She avoided rejecting him directly because he was involved in her treatment, and turning him away risked losing medical attention she needed. Tanzler, however, believed her reluctance was modesty.

He began inserting himself into her life immediately. He proclaimed his love for her, brought gifts jewelry, clothing, perfumes and behaved as if a relationship existed between them. He told others he could cure her tuberculosis.

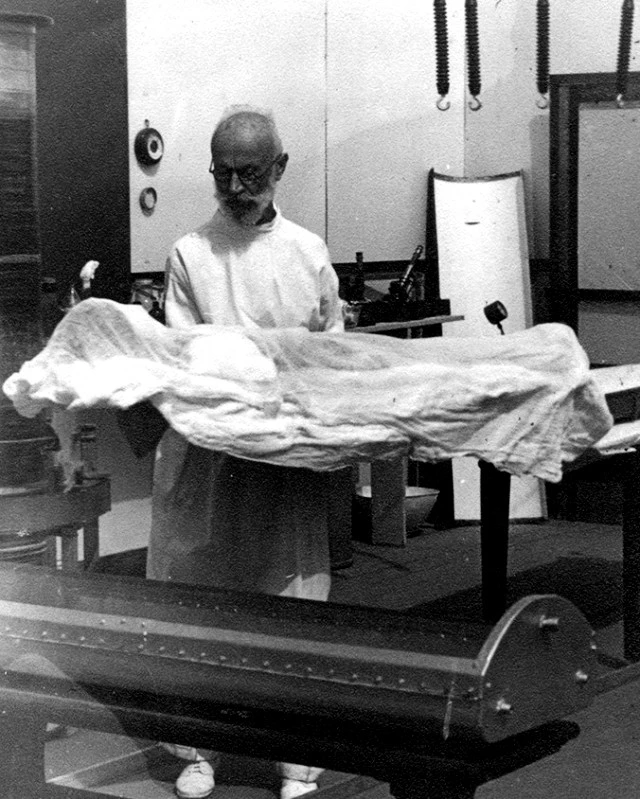

At his home, he mixed what he called “elixirs,” “tonics,” and homemade medicines. He brought these to Helen’s family home daily and administered them himself. He stole hospital equipment, including X-ray machines and electrical devices, and moved them into the de Hoyos home to perform unauthorized treatments.

Tanzler’s autobiography later portrayed Helen as dependent on him, claiming she “begged for his help.” Her family strongly contradicted this, saying she was uncomfortable around him and simply tolerated his presence because of her deteriorating condition.

As her illness progressed, Tanzler’s behavior grew more intense. He ignored medical reality and insisted he alone could save her. In truth, Helen’s condition continued to decline, and nothing he did altered the course of the disease.

Helen’s Death

Helen de Hoyos died on 25 October 1931 from tuberculosis. Tanzler was devastated and immediately blamed her family, calling them “ignorant” and “ungrateful” for not fully supporting his unproven treatments. Her relatives later said his behavior during her illness had made them increasingly uncomfortable.

After her death, Tanzler went even further. He purchased the house Helen had lived in so he could sleep in her room, claiming the bed still “smelled like her.” He also insisted on paying for her funeral, and the family grieving and overwhelmed agreed.

He commissioned a costly above-ground mausoleum for her at the Key West Cemetery. Tanzler told the family he wanted to protect her from moisture, dirt, and groundwater. What he never disclosed was that he arranged the structure so only he would have a key. The family had no ability to enter the crypt.

For nearly two years, he visited her tomb nightly. He brought instruments, chemicals, and containers of formaldehyde, attempting to slow the natural decay of her body. The work was amateur and ineffective. Decomposition progressed despite his efforts.

His behavior soon crossed into delusion. He later claimed Helen “spoke” to him from inside the mausoleum. He said she encouraged his presence and reassured him that she knew he was trying to save her. He serenaded her body at night with his favorite Spanish song, believing she responded.

Tanzler attempted extreme measures to “restore” her. He tried force-feeding the corpse using tubes he inserted into her mouth. On other occasions he attempted to feed her by pressing his own mouth to hers, convinced she needed nourishment to regain strength. None of these attempts slowed decomposition.

By 1933, he claimed Helen’s spirit was pleading with him to take her home. He took this as permission for the next escalation of his obsession.

Removal of the Body

In April 1933, nearly two years after the burial, Tanzler removed Helen’s body from the mausoleum. He waited until after dark, carried her corpse out of the crypt, and placed it into a small toy wagon. He pulled the wagon through the cemetery and brought her body to his home without anyone noticing.

By this time, decomposition was severe. The body had already begun to liquefy months earlier, and after two years in the mausoleum it was largely skeletal. Despite this, Tanzler believed he could restore her to the appearance she had in life.

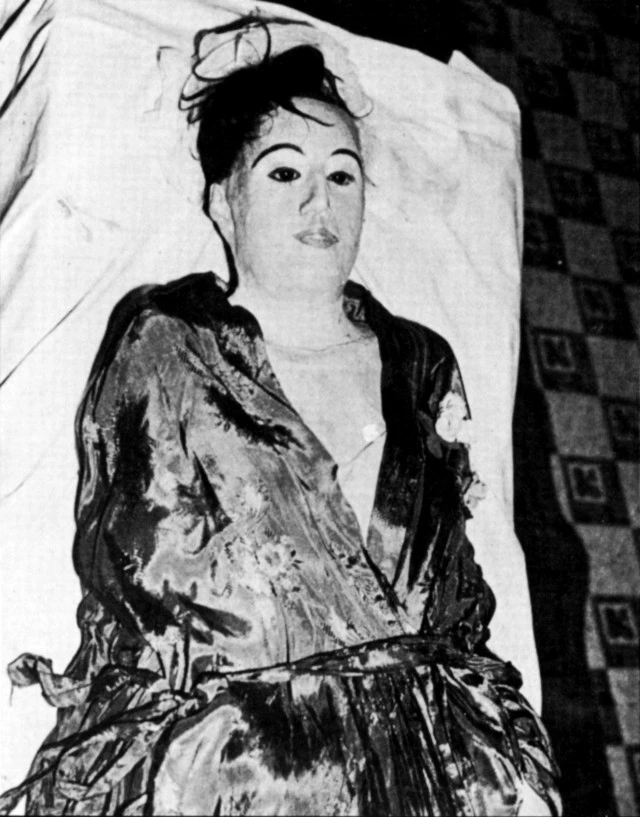

Behind his house sat an old airplane fuselage that he had converted into a makeshift laboratory. He brought Helen’s remains into this space and began reconstructing her. He wired her bones together using piano wire and coat hangers to stabilize her frame. He created glass eyes to place into her empty sockets.

He stuffed the torso and abdominal cavity with rags to fill the areas where tissue had collapsed. Most of her skin was gone, so he built an outer layer using silk cloth that he coated with wax and plaster of Paris, effectively creating a papier-mâché shell over the surviving remains. He then fashioned a wig using hair from his own mother.

Tanzler dressed the rebuilt body in gloves, stockings, jewelry, and the clothing Helen had worn on the day she died. He also created multiple death masks facial molds made directly from her remains and kept them in case he needed to replicate parts of her appearance.

He moved her body into his bed and lived with her for the next seven years. He bathed her, applied perfumes, and treated the corpse as if she were alive. Foul odors filled his home due to ongoing decomposition; he attempted to mask the smell with disinfectant and large amounts of perfume, but the stench persisted.

Rumors eventually spread through Key West. Residents noticed Tanzler known for being reclusive purchasing women’s clothing, perfume, and personal items. A young boy later reported seeing him through a window dancing with what he believed was a large doll. No one suspected the figure was a human corpse.

Discovery

By 1940, years of rumors circulated in Key West. Neighbors spoke about the reclusive German man who bought women’s clothing and perfume despite living alone. Some mentioned the persistent odor around his property. Others recalled a young boy who claimed he saw Tanzler dancing inside his home with what looked like a life-sized doll.

These stories eventually reached Helen’s sister, Florinda “Nana.” Concerned and suspicious, she went to Tanzler’s house unannounced. Through a window, she saw him holding and dancing with a figure that resembled her sister something far too large and lifelike to be a doll.

Nana immediately contacted authorities. Police entered the home and confirmed the figure was not a mannequin but the preserved and altered remains of Helen de Hoyos. The reconstruction was so extensive that officers initially struggled to identify what parts were original.

Tanzler was arrested and charged with grave robbing and maliciously destroying a grave, the only offenses available under Florida law at the time. He did not deny taking the body. He explained his actions in detail and insisted Helen wanted to be with him.

A psychiatric evaluation was conducted. Despite the circumstances, examiners declared him competent to stand trial.

During the investigation, Tanzler revealed a long-term plan he had devised. He said he intended to send Helen’s body “high into the stratosphere” inside a rocket-like craft of his own design, believing cosmic radiation from outer space would penetrate her tissues and restore her to life.

Public Reaction

The case exploded in the national press as soon as the details became public. Newspapers treated it as a morbid spectacle, and the unusual nature of the crime drew widespread attention. The public fixated on the story of a man who had lived with a corpse for seven years.

After authorities recovered Helen’s body, she did not receive an immediate burial. Instead, the remains were placed on display at the Dean-Lopez Funeral Home. Nearly 7,000 people came to view the body out of curiosity, a decision that further delayed her opportunity for dignity in death.

Despite the severity of the desecration, the legal case against Tanzler collapsed. Florida’s statute of limitations for grave tampering had already expired, and the charges had to be dismissed. After spending only a short period in custody, he was released.

Reaction to his release was unexpectedly sympathetic. Tanzler began receiving large amounts of fan mail from people many of them women who praised his “devotion” and described his actions as romantic rather than criminal. Some even offered themselves to him as potential partners.

Tanzler responded publicly. In interviews and in the opening pages of his later autobiography, he portrayed himself as a victim of sensational journalism. He complained that he had been labeled a “ghoul,” a “fiend,” and a “pervert,” insisting he had only acted out of love. He accused Helen’s family of jealousy and greed, claiming they involved police for personal gain.

Public fascination with the case continued, but legal options were exhausted. Tanzler walked free, while Helen was ultimately buried in an unmarked grave at an undisclosed location to prevent further interference.

Later Years

After his release, Tanzler left Key West and moved to Pasco County, Florida. He settled near his first wife, Doris, although they did not reunite. Despite everything he had done, she remained supportive of him, corresponding with him and helping him manage basic needs.

During this time, Tanzler learned that one of their daughters, Clarista, had died in 1934 from diphtheria while he had been living with Helen’s corpse in Key West. He wrote little about this loss, and there is no record that he ever returned to see his surviving daughter.

Alone in Pasco County, he recreated a version of the life he had lost when the body was taken from him. Using the death masks he had molded from Helen’s face years earlier, he built a new effigy a life-sized figure meant to represent her. He kept this effigy in his home and lived beside it for the rest of his life.

Tanzler died on 3 July 1952 at age 75. His body went undiscovered for three weeks. Some later accounts claimed he was found lying in the arms of the effigy, though his obituary reported he was found on the floor behind one of his organs, likely referring to a musical instrument rather than human remains.

With no close family present and no public memorial, Tanzler died as he had lived for decades isolated, fixated on a woman who had never returned his affection.

Final Notes

After authorities recovered Helen’s body in 1940, she was eventually reburied in the Key West Cemetery. This time the grave was unmarked, and the location was kept secret. The decision was made to prevent anyone including Tanzler from accessing her remains again.

Tanzler later wrote an autobiography titled The Secrets of Elena’s Tomb: The Confessions of Carl von Cosel. In it, he reframed his actions as acts of devotion and maintained that he had been misunderstood. His writing offered insight into his delusions but provided little remorse for the harm he caused.

Public fascination with the case never fully faded. The combination of obsession, grave desecration, improvised preservation techniques, and the failure of the legal system created one of the most disturbing and widely discussed cases in American true-crime history.

The legacy of the case rests on several unresolved issues. It exposed gaps in Florida’s laws on handling human remains. It sparked ethical debates about consent, dignity after death, and the treatment of victims in media. And it underscored how unchecked fixation combined with access, opportunity, and delusion can continue long after a victim is unable to protect themselves.

More than ninety years later, the story remains a grim example of how far one man’s obsession went, and how little protection Helen de Hoyos received in life or in death.