On September 6, 1992, hunters following the Stampede Trail near Healy, Alaska, pushed open the door of an abandoned city bus. The stench inside stopped them cold. A sleeping bag lay stretched across a bunk. Inside it, they found the emaciated remains of a young man.

Police later confirmed his name: Christopher McCandless. Only 24 years old, he had walked into the Alaskan wilderness four months earlier, determined to live off the land. His journey idealistic, reckless, and unforgettable would capture the imagination of millions.

The Discovery in the Alaskan Wild

The bus where McCandless died was Fairbanks City Transit Bus 142, left decades earlier as shelter for road workers. By 1992 it was weathered and rusting, a forgotten relic on the edge of Alaska’s wild.

When troopers searched it, they uncovered five rolls of exposed film, journals written on the blank pages of a plant guide, scattered possessions, and a hand-written note taped to the door. It read, on a page torn from a Gogol novel:

“S.O.S. I need your help. I am injured, near death, and too weak to hike out of here. I am all alone… This is no joke. In the name of God, please remain to save me. Thank you. Chris McCandless. August?”

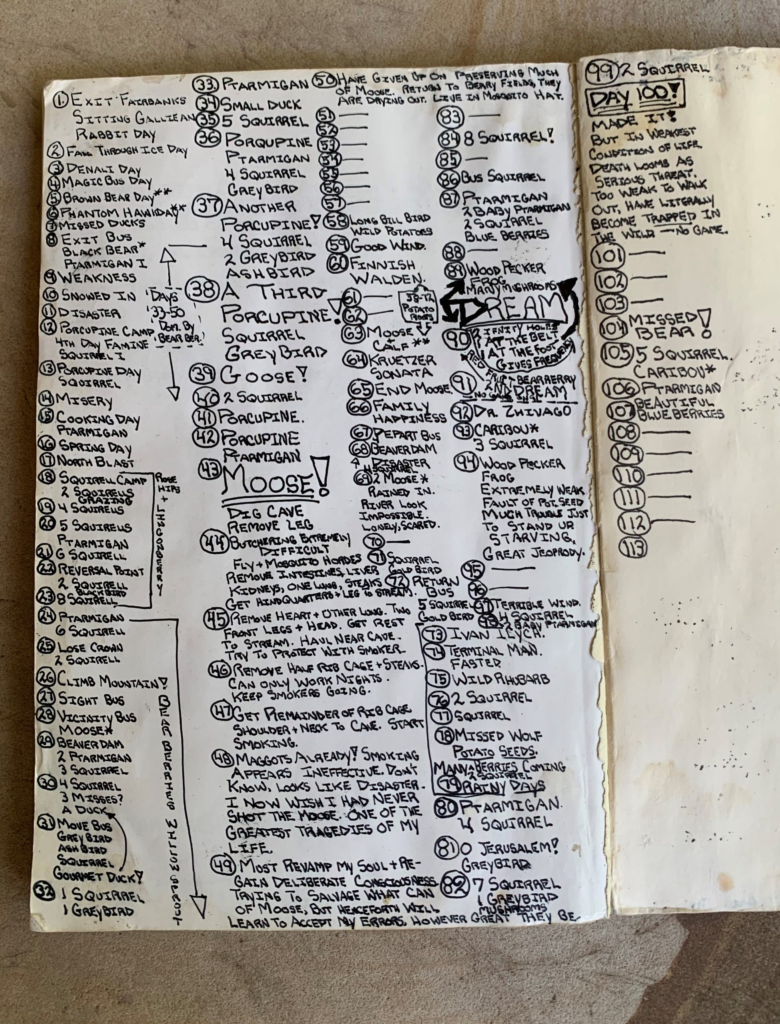

The note gave investigators their first glimpse into McCandless’s final weeks. His diary, kept until Day 112, told the rest. He had lasted nearly four months, but starvation and isolation had left him too weak to continue.

A Restless Young Man

Christopher Johnson McCandless was born on February 12, 1968, in El Segundo, California, and grew up in suburban Virginia. From a young age he devoured books Jack London, Leo Tolstoy, Mark Twain stories of wilderness, freedom, and rejection of society’s constraints. Those themes shaped him deeply.

Home life was complicated. His father, Walt, worked as an aerospace engineer, and his mother, Billie, managed the household. Behind the image of middle-class success, however, McCandless clashed bitterly with his parents.

He saw them as materialistic and controlling, pushing him toward a conventional path he wanted no part of. His sister later described a home scarred by volatility and distance.

McCandless, however, thrived on self-reliance. By eight he was hiking and camping with unusual determination, pushing himself farther than other children his age. In high school and college, he cultivated an independent streak running long distances, working odd jobs, always testing limits.

By the time he graduated from Emory University in Atlanta in 1990 with high grades in history and anthropology, his plan was set. He would leave behind his parents’ expectations, discard possessions, and find what he called a “more authentic life.”

His first step was radical. He donated nearly all of his savings about $24,000 to Oxfam. What cash remained, he burned in the desert. Then, packing a few belongings into his yellow Datsun, he drove west.

Soon after, he vanished from the world he had known. Friends and family would not hear from him again. On the road, he shed his given name and became “Alexander Supertramp.”

Into the Wilderness

For nearly two years, McCandless drifted across the American West. When his yellow Datsun was trapped in a flash flood in Arizona, he simply abandoned it and hitchhiked onward. He harvested wild plants, hopped freight trains, and worked short stints when money ran dry.

At a grain elevator in South Dakota he labored for Wayne Westerberg, who later recalled him as intelligent, restless, and stubbornly independent.

Adventure defined these years. He paddled a kayak down the Colorado River into Mexico, camped alone in the desert, and wandered through cities with little more than a backpack. To some, his rejection of comfort was inspiring.

To others, it was reckless. But McCandless remained committed to his vision: life stripped down to essentials, free from what he saw as society’s corruption.

By spring 1992 he set his sights on Alaska the “Great White North” he had dreamed of since childhood.

On April 28, 1992, a local electrician named Jim Gallien picked up a hitchhiker who introduced himself only as “Alex.” He carried a light pack, a .22-caliber Remington Nylon 66 rifle, a bag of rice weighing ten pounds, and a handful of books but no map, no compass.

Gallien was alarmed. He offered to buy him better equipment, but McCandless refused. Instead, he left his map, watch, comb, and even 85 cents in Gallien’s truck.

He did accept a pair of rubber boots and a tuna melt sandwich before stepping off into the brush.

Three days later he found Bus 142. Left decades earlier as a shelter for road crews, the bus became his base. Here, McCandless hunted small game, foraged berries, and kept a journal.

In June he shot a large animal likely a caribou, though he believed it a moose but failed to preserve the meat, calling it “one of the greatest tragedies of my life.”

By July his food supply was dwindling. On July 3 he tried to leave, but when he reached the Teklanika River, the spring melt had transformed it into a raging torrent. Crossing was impossible. What he didn’t know: a hand-operated cable tram lay only a quarter mile downstream, and an NPS cabin stocked with food and supplies sat six miles away.

Without a map, he never discovered them.

Trapped, he returned to the bus. In August he posted the SOS note on the door, signaling that his strength was failing.

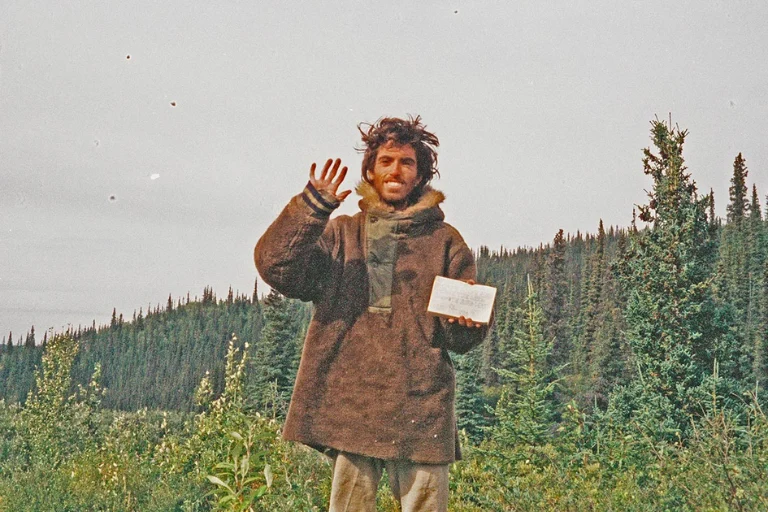

His diary grew sparse “Day 100! Made it! But in weakest condition of life. Death looms as serious threat.” His final entry was Day 112; there is no Day 113.

On a torn page he wrote his last message: “I have had a happy life and thank the Lord. Goodbye and may God bless all!” He took a self-portrait holding the note.

He likely died on August 18, 1992.

Legacy of the Magic Bus

Nineteen days after his death, hunters opened the door of Bus 142 and found him. The autopsy listed starvation as the cause. He weighed just 67 pounds. Among his belongings were the SOS note, his diary, and rolls of exposed film that documented his life in the wild.

News of McCandless’s life and death spread quickly. Jon Krakauer’s 1996 book Into the Wild brought his story to a global audience, later adapted into a 2007 film.

To some readers, he was a symbol of courage a young man rejecting convention in search of truth. To others, he was dangerously naïve, a romantic idealist fatally unprepared for Alaska’s realities.

The bus itself became a shrine. Pilgrims hiked the Stampede Trail to see where “Alexander Supertramp” had lived and died, scrawling tributes on its walls. But the journey was treacherous. Dozens of hikers needed rescue. In 2010 and again in 2019, visitors drowned trying to cross the Teklanika River the same barrier that had trapped McCandless.

By 2020, authorities had enough. On June 18, a National Guard helicopter lifted Bus 142 out of the wild and flew it to Fairbanks.

Today it is conserved at the University of Alaska Museum of the North, with plans for a permanent outdoor pavilion opening in 2026.

Christopher McCandless remains a figure of paradox. He sought simplicity, yet died because he was unprepared. He rejected society, yet his story inspired millions within it. For some, he is a cautionary tale. For others, a call to live with greater intensity.

Either way, the line he marked in Doctor Zhivago “Happiness is only real when shared” still echoes, the final testament of a young man who walked alone into the wild.