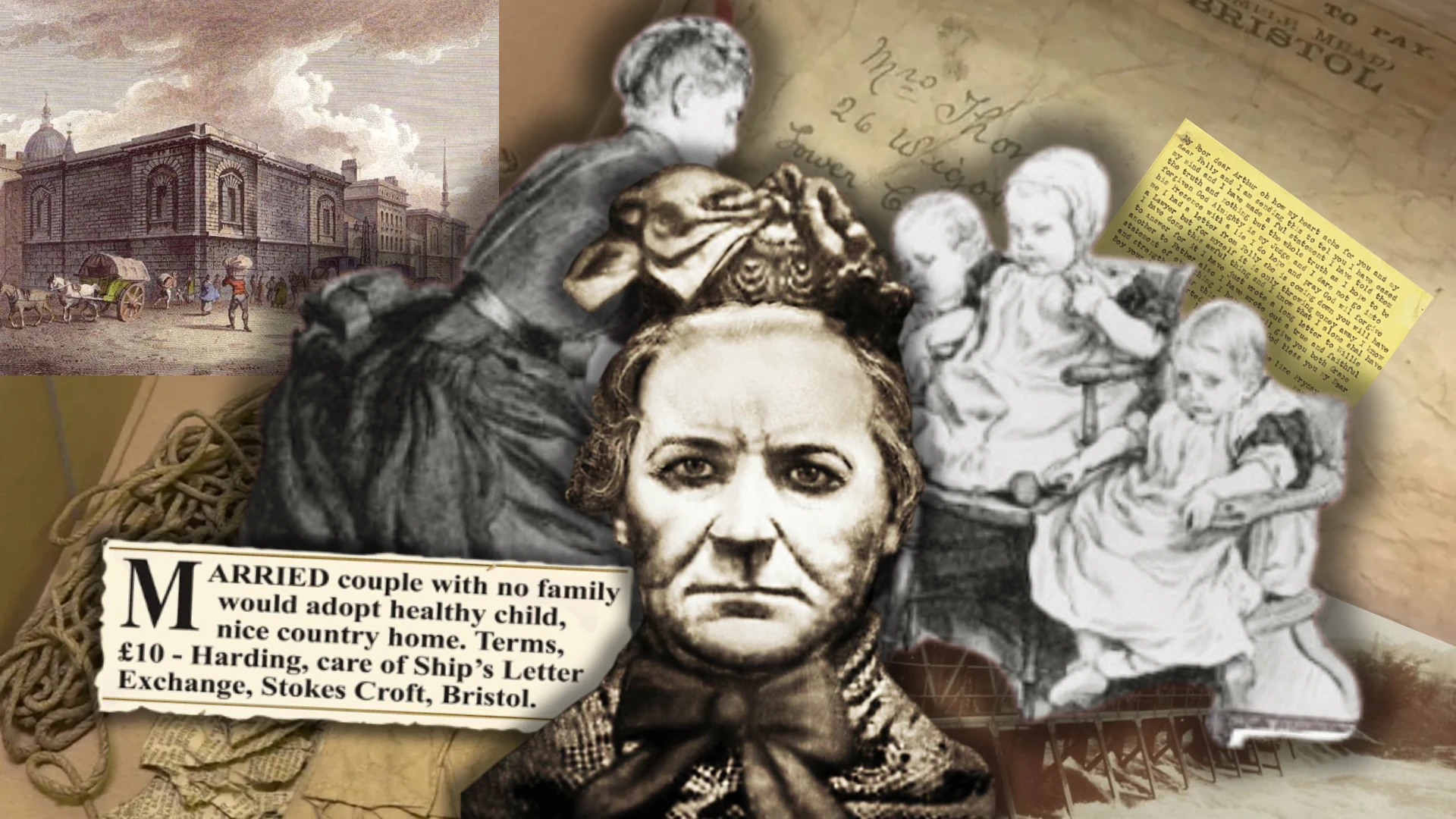

For nearly three decades, Amelia Dyer placed advertisements in provincial newspapers posing as a loving adoptive mother, collected one-time fees from desperate young women, and strangled their infants with white dressmaking tape — disposing of the bodies in the River Thames. By the time Reading police arrested her in April 1896, estimates of her victim count had already exceeded 400 children.

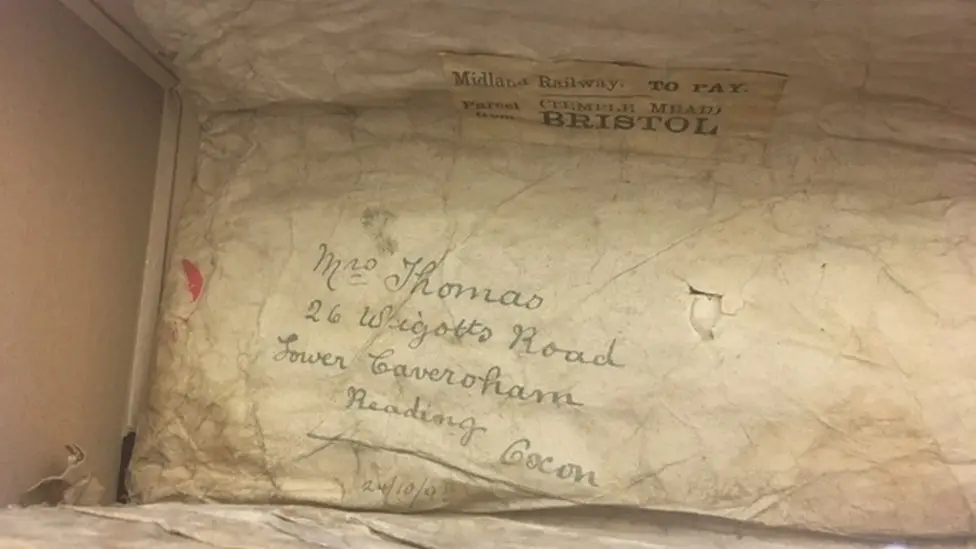

On March 30, 1896, a bargeman working the stretch of the River Thames near Reading, Berkshire, pulled a waterlogged brown paper parcel from the current. Inside was the body of a baby girl, later identified as Helena Fry. The parcel had been weighted with a brick. It had been forced through iron railings into the water. It had not sunk far enough.

Investigators gave the package to Reading Borough police. On the wrapping, microscopic analysis recovered a faintly legible name — Mrs. Thomas — and a Bristol address. A label from Temple Meads station, Bristol, confirmed the parcel had traveled. Both the name and the address led to the same woman. Neither belonged to anyone innocent.

The woman behind them was Amelia Dyer, born Amelia Hobley in 1838 in the small village of Paya Marsh, east of Bristol. She had spent nearly three decades perfecting a method of murder so efficient it would eventually prompt a parliamentary scandal, a complete overhaul of British adoption law, and a press-given title she carried to the gallows: the Ogress of Reading.

Dyer’s Early Life

Amelia was the youngest child of Samuel and Sarah Hobley, and grew up in a household shaped early by catastrophe. Her mother suffered severe mental illness caused by typhus. Amelia witnessed her mother’s violent fits and assumed responsibility for her care until Sarah’s death in 1848, when Amelia was ten years old. She was, by multiple accounts of her early years, a good student with a particular affinity for literature and poetry. The illness in her home left its mark regardless.

After her mother died, Amelia moved to Bristol to live with an aunt and found work as a corset maker. Her father, Samuel, died in 1859. His eldest son Thomas inherited the family shoe business. In 1861, at the age of 24, Amelia became permanently estranged from at least one of her brothers, James, and moved into lodgings on Trinity Street, Bristol. There she met George Thomas, a widower of 59 — thirty-five years her senior. They married. To compress the age gap on the marriage certificate, George deducted eleven years from his age and Amelia added six to hers.

After the marriage, Amelia trained as a nurse, then a respectable occupation that provided her with skills she would spend the rest of her life exploiting. Life as a nurse, however, was hard. Through a contact named Ellen Dane, a midwife, Amelia discovered a considerably easier way to earn a living. Ellen Dane fled to the United States shortly after their meeting to escape the attention of British authorities. Amelia stayed and went to work.

Victorian England’s Baby Trade

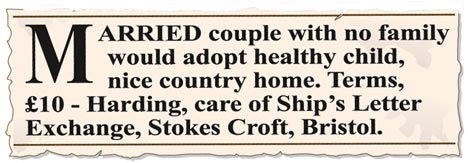

The world Amelia entered had been shaped for her by legislation. The 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act had stripped unmarried fathers of any legal obligation to financially support the mothers of illegitimate children. Young unmarried women who fell pregnant had no legal recourse, no institutional support, and frequently no family willing to acknowledge their situation. Into that vacuum grew the practice known as baby farming, in which men and women advertised themselves as adoption or fostering agents in exchange for a fee from the baby’s mother.

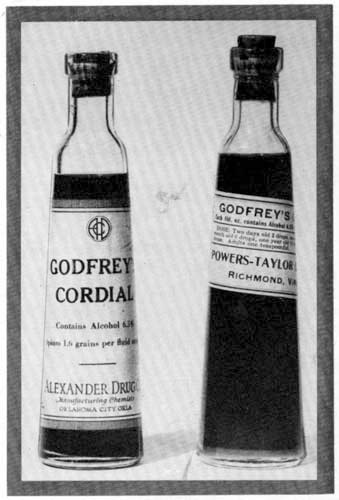

Some baby farmers provided genuine care. Others extracted their fees and allowed the children to die of starvation and deliberate neglect. The most widely used method of concealment was sedation. Godfrey’s Cordial, a commercially sold syrup better known by its street name, Mother’s Friend, contained opium and was routinely administered to infants by baby farmers looking to reduce their workload. The drug killed more infants through starvation than it did through overdose: a baby fed opium continuously lost the will and ability to eat, and eventually died of malnutrition. Coroners examining such deaths recorded them as debility from birth, lack of breast milk, or simple starvation. No investigation followed.

The fee structure reflected the desperation of the clients. Well-off parents anxious to conceal an illegitimate birth might pay as much as £80 for a discreet adoption arrangement. If a father simply wanted his identity protected, £50 might be negotiated.

For the majority of clients, who were poor young women with no leverage and few alternatives, the going rate was £10. In 1870, £10 was equivalent to approximately £850 today. Mothers who later wanted to reclaim their children, or who grew suspicious about their welfare, frequently found they had no legal standing to demand answers.

Many were too frightened or ashamed to go to the police at all. Even authorities who tried to investigate found it nearly impossible to trace missing children through the informal, unregulated networks of the baby farming trade.

The Business of Murder

George Thomas died in 1869, leaving Amelia without income. She had already left nursing following the birth of her daughter Ellen. Baby farming, she had learned, could be far more profitable, and her nurse’s training gave her the additional credibility that secured clients. She began advertising to nurse and adopt babies in exchange for a substantial one-time payment and adequate clothing for the child. In her advertisements and in her meetings with clients, she presented as warm, domestic, and unimpeachably respectable.

At some point in her long career, Amelia abandoned even the pretense of allowing children to die slowly through starvation and sedation. Shortly after collecting each child and its fee, she killed them. She used white dressmaking tape, wound twice around the throat and knotted. The method was quick, left no visible external marks that would concern a casual observer, and left the full fee intact. No portion needed to be spent on food, medicine, or accommodation for a child who no longer existed.

She evaded discovery for years. In 1879, a doctor grew suspicious about the number of infant deaths he had been called to certify in her care and reported her to the authorities. Strangely, the charge that followed was not murder or manslaughter but neglect. She was sentenced to six months of hard labor. After serving the sentence, she disappeared into the first of several mental hospital admissions, presenting symptoms of instability sufficient to warrant confinement.

As a former nurse with direct experience of asylum operations, she knew precisely how to behave to secure a relatively comfortable stay. Each admission, the prosecution would later note, coincided exactly with the periods of greatest professional danger.

The 1890 Governess Incident

In 1890, Amelia agreed to care for the illegitimate infant of a governess. When the governess returned to visit her baby some time later, something made her uneasy. She stripped the infant to check for a distinctive birthmark she knew would be present on its hips. It was not there. The child was not hers.

The governess reported this to the authorities. When investigators began to close in, Amelia drank two full bottles of laudanum in what appeared to be a serious suicide attempt. Her years of consuming opium-based products had built up a tolerance so substantial that she survived. Due to insufficient evidence, no prosecution followed. She returned to baby farming. She returned to murder.

By this stage, Amelia had concluded that involving doctors to issue death certificates created unnecessary risk. She began disposing of the bodies herself. Aware that the scope and pattern of her activities generated attention, she relocated frequently, moving herself and her immediate circle through different towns and cities across England to escape suspicion, shed accumulated scrutiny, and establish new client networks from scratch. Over the years she operated under many different identities.

Reading, 1895

In 1895, Amelia moved to Caversham, Berkshire, accompanied by three people. The first was a woman known as Granny Smith, an associate Amelia had recruited during a brief spell in a workhouse, whose function was to act as a plausible domestic presence. The second was Amelia’s daughter Marianne, known as Polly, then 23 years old.

The third was Polly’s husband, Arthur Palmer. Later that same year, the household relocated again, to Kendon Road, Reading. Granny Smith had been persuaded to present herself to clients as Polly’s mother, allowing the household to project the image of an established, multigenerational family offering a safe and caring home.

In January 1896, a 25-year-old barmaid named Evelina Marmon gave birth to an illegitimate daughter in a boarding house in Cheltenham. She named the baby Doris. Unable to raise the child alone, and hoping eventually to return to work and reclaim her daughter once her circumstances improved, Evelina placed an advertisement in the miscellaneous section of the Bristol Times and Mirror. It read simply: ‘Wanted: respectable woman to take a young child.’

The advertisement placed immediately next to hers read: ‘Married couple with no family would adopt healthy child — nice country home — terms £10.’

The Letter from Mrs. Harding

Evelina responded. Within days she received a reply from a Mrs. Harding, writing from Oxford Road, Reading. The letter read:

‘I should be glad to have a dear little baby girl one I could bring up and call my own. We are a plain homely people in fairly good circumstances. I don’t want a child for money’s sake but for company and home comfort — myself and my husband are dearly fond of children. I have no child of my own. A child with me will have a good home and a mother’s love.’

Mrs. Harding was Amelia Dyer.

Evelina had hoped to negotiate a more affordable weekly fee for Doris’s care. Mrs. Harding would not hear of it. The arrangement required a single upfront payment of £10, in full, in advance. Evelina, in difficult financial circumstances and without alternatives, reluctantly agreed.

On the appointed day, Amelia arrived in Cheltenham. Evelina was startled by her age and appearance — she had not expected someone so elderly. Amelia was affectionate toward Doris throughout the meeting. Evelina packed a cardboard box of the baby’s clothes, handed her daughter to the woman she knew as Mrs. Harding, and gave over the £10. She accompanied Amelia as far as Chapman station. She returned to her lodgings in tears.

A few days later, she received a letter from Mrs. Harding saying that all was well. Evelina wrote back immediately. She received no reply.

76 Mayo Road

Amelia had not traveled where she told Evelina she was going. She went instead to 76 Mayo Road, Willesden, London, where Polly was staying. There she found white dressmaking tape and wound it twice around Doris Marmon’s neck. She knotted it. Doris was seven months old.

Polly allegedly helped to wrap the body in a napkin. Some of the clothes Evelina had packed for her daughter were kept. The rest were sold at the local pawnbroker. Amelia paid her rent to the landlady and gave her a pair of the dead baby’s boots as a gift for the landlady’s own little girl.

The following day, Wednesday, April 1, 1896, a second child was brought to Mayo Road. His name was Harry Simmons. He was 13 months old. No spare white tape was available. The tape wound around Doris Marmon’s body was removed and used to strangle Harry Simmons. On April 8, both bodies were packed into a carpet bag along with bricks for weight. Amelia traveled to Reading and forced the bag through iron railings near Caversham Lock into the River Thames.

The Investigation

The river had already betrayed her. Three days before Amelia disposed of Doris and Harry, on March 30, 1896, the bargeman at Reading had recovered Helena Fry’s body. The wrapping paper had yielded its fragment of a name. Reading police had Amelia Dyer in their sights before she committed the last of her documented murders.

They placed her under surveillance and arranged for a young woman to act as a decoy, posing as a prospective client seeking Amelia’s adoption services. A meeting was scheduled for April 3 — Good Friday. Amelia came to her door expecting a nervous young mother. She found the Reading police instead.

Searching the house, investigators were immediately struck by the smell of human decomposition. No human remains were found in the house. Everything else was. White dressmaking tape. Telegrams and letters documenting adoption arrangements. Pawn tickets for items of children’s clothing. Receipts for newspaper advertisements. Letters from mothers asking after the well-being of their babies. In the previous few months alone, at least 20 children had been placed in the care of Mrs. Thomas — one of Amelia’s operating identities. She had, police noted, been preparing to move again, this time to Somerset. She would not get the chance.

Amelia was arrested on April 4 and charged with murder. Her son-in-law, Arthur Palmer, was charged as an accessory. Through April, the Thames was systematically dredged. Six more bodies were recovered. Among them were Doris Marmon and Harry Simmons. Every child had been strangled with white tape.

Eleven days after handing her daughter to the woman she knew as Mrs. Harding, Evelina Marmon was brought to identify Doris’s remains at the inquest.

The Trial

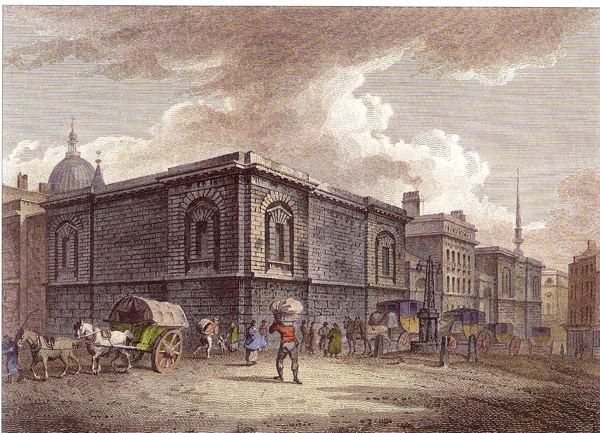

At the inquest in early May, no evidence was found that Polly or Arthur Palmer had acted as Amelia’s deliberate accomplices. Palmer was discharged. On May 22, 1896, Amelia Dyer appeared at the Old Bailey and pleaded guilty to one murder: that of Doris Marmon.

Her family took the stand against her. They testified that they had grown increasingly suspicious and uneasy about her activities over the previous months, and that she had narrowly escaped exposure on several prior occasions. A man who had witnessed her force a carpet bag through railings into the water near Caversham Lock gave evidence. Polly provided graphic testimony that confirmed her mother’s guilt. The only defense Amelia offered was insanity, citing her two prior commitments to Bristol asylums as evidence of mental instability.

The prosecution dismantled it systematically. Both asylum admissions, they argued, had coincided precisely with periods when Amelia believed her crimes were on the verge of exposure. Her instability had not been a symptom. It had been a strategy. The jury deliberated for four and a half minutes.

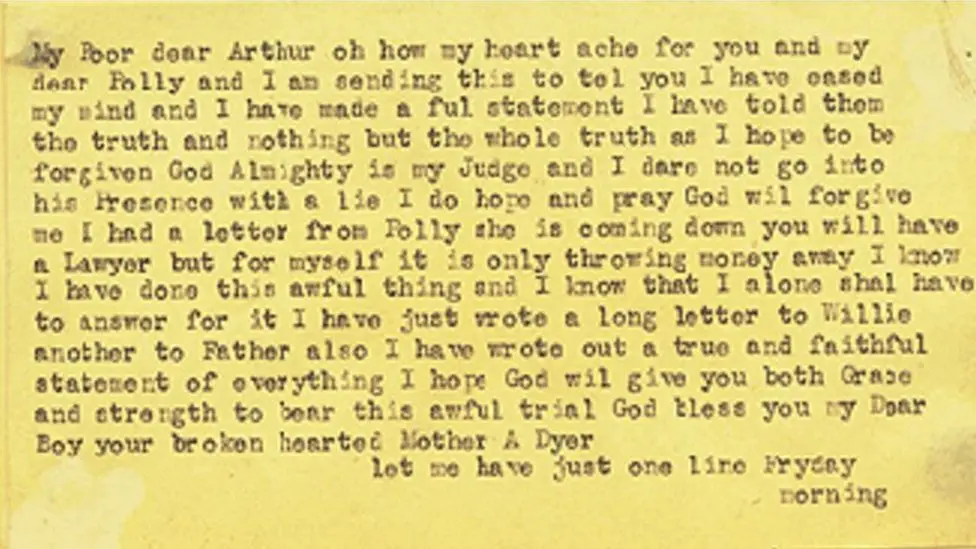

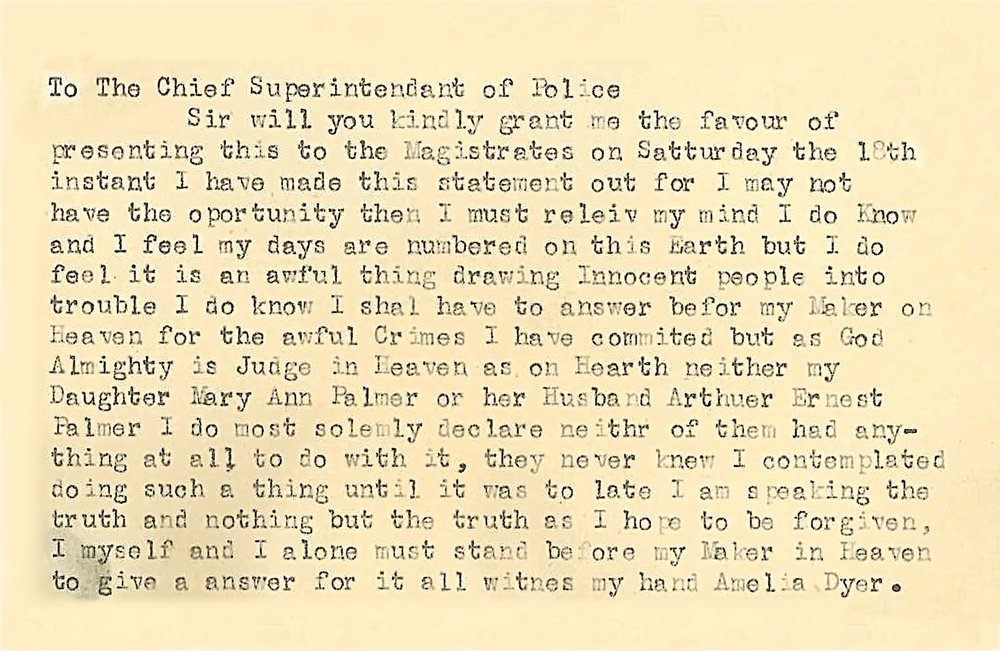

The Confession

Amelia spent three weeks in the condemned cell at Newgate Prison. She used the time to fill five exercise books with what she described as her last true and only confession — a document whose full contents were never made public. The night before her execution, a prison chaplain visited her and asked whether she had anything to confess. She held out the five exercise books. ‘Isn’t this enough?’ she said.

The question of how many children Amelia Dyer killed across nearly three decades of operation was never resolved. The evidence recovered from her various homes — letters from hundreds of mothers, quantities of infant clothing, adoption receipts spanning decades, records of dozens of identities and addresses — pointed far beyond the six bodies recovered from the Thames in April 1896. Some estimates, based on the scope of her advertising activity and the duration of her career, place the total death toll above 400. She is widely considered one of the most prolific murderers in British history.

The Aftermath

The Amelia Dyer case caused a scandal that reached Parliament. In its wake, adoption laws in Britain were overhauled, granting local authorities new powers to inspect and regulate baby farms. Provincial newspapers faced heightened scrutiny of their personal advertisement sections. Baby farming did not stop. It became harder to conceal.

Amelia Dyer was hanged at Newgate Prison on Wednesday, June 10, 1896. She was 57 years old. Asked on the scaffold whether she had anything to say, she replied: ‘I have nothing to say.’

Two years after her execution, railway workers inspecting carriages at Newton Abbot station in Devon opened a parcel they found inside a train car. It contained a three-week-old girl. She was cold and wet but she was alive. A woman named Jane Hill had paid £12 to hand the baby to a Mrs. Stuart in Plymouth. Mrs. Stuart had collected the infant, boarded the next train, and left her there. The woman believed to have been Mrs. Stuart was later identified as Polly, Amelia Dyer’s daughter, who had watched her mother strangle Doris Marmon and Harry Simmons, given evidence at the Old Bailey, and returned to baby farming within two years of the hanging.