On the morning of November 1941, inside an operating room in Washington D.C., a 23-year-old woman was strapped to a table, her head shaved, and kept wide awake. The doctors asked her to sing songs. They asked her to recite prayers. She did until, at some point during the procedure, she simply went quiet.

The attending nurse quit medicine the same day. She never returned to the profession.

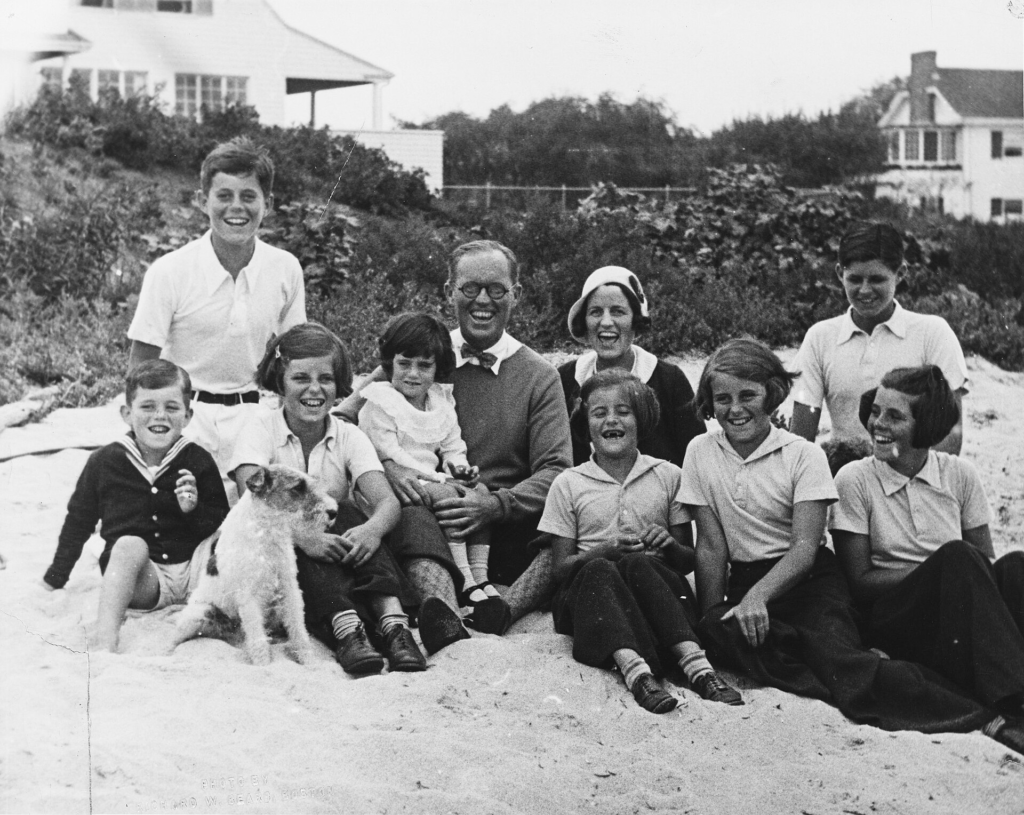

The young woman on that table was Rosemary Kennedy — the third child of one of the most powerful families in America, a bright and beautiful girl who had danced at Buckingham Palace, filled her diary with descriptions of European royalty, and been called ‘exquisite’ by the British press. Within hours, she was gone. Not dead but, in the ways that mattered to her family, erased.

What had been done to her, and on whose orders, would not be spoken of in the Kennedy household for over twenty years.

A Delayed Birth Robs Rosemary Kennedy of Oxygen and Changes Her Forever

Rose Marie Kennedy known to her family as Rosemary was born on September 13, 1918, the third child of businessman and politician Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. and his wife, Rose Elizabeth Fitzgerald. The timing could not have been worse. The Kennedy family was living in Brookline, Massachusetts, at the height of the Spanish flu epidemic, a pandemic that would ultimately kill between 20 and 50 million people worldwide. The city’s hospitals were overwhelmed. Rose’s own doctor was unavailable when labor began.

What happened next would define the rest of Rosemary’s life. As documented in the book The House of Kennedy, the presiding nurse ordered Rose to squeeze her legs together to delay the birth and, incredibly, went so far as to push the baby’s partially exposed head back into the birth canal.

For two hours, the infant was deprived of oxygen while the family waited for the doctor to arrive. When he finally did, he delivered a baby girl and pronounced her healthy.

The Kennedys believed him. For a time.

But as little Rosemary grew, the signs became harder to ignore. She was slower to crawl than her brothers Joe Jr. and John. Slower to walk. Slower to speak. Her younger siblings eventually numbering seven continued to develop at a pace that made the gap between them and their eldest sister unmistakable.

Specialists confirmed what the family had come to suspect: the oxygen deprivation at birth had caused lasting intellectual disability.

The diagnosis, delivered to one of America’s most ambitious families at the height of the eugenics movement, was treated not as a medical reality to be accommodated, but as a secret to be contained.

Her Family Hides Her Condition and Demands She Keep Up

The eugenics movement had taken hold among the American elite in the early 20th century, with its adherents believing that certain individuals including those with intellectual disabilities carried defective genes and were social liabilities.

For the Kennedys, who were also prominent Catholics at a time when the Church denied disabled people communion and confirmation a remnant of the old belief that mental disability was evidence of demonic possession the implications of Rosemary’s condition were both social and spiritual. Exposure could mean ruin.

So Rosemary was packed off to a succession of boarding schools, making it easier to keep her condition from their social circle. She was shielded from public view. But the Kennedys also doted on her.

They went out of their way to include her in family activities and public events. A teenage Rosemary filled her diary with vivid, enthusiastic descriptions of the dignitaries she met, the dances she attended, the concerts she went to. She was, by all accounts, warm, sociable, and genuinely happy in the right environment.

The right environment, however, was not the Kennedy household. As the John F. Kennedy National Historic Site noted, the Kennedy siblings were fiercely competitive, and their parents demanded achievement from all of them.

Rosemary grew frustrated that she could not match her brothers and sisters. And rather than lower those expectations, her parents raised them — convinced, against all evidence, that holding her to the same standard as everyone else would cure her. Specialized education and experimental treatments were layered on top of this thinking. None of it worked. Her intellectual abilities never progressed beyond a fifth-grade level.

Rosemary Finds Happiness in London, Then Loses Everything

In 1938, Joseph Kennedy Sr. was appointed United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom, and the entire family relocated to London. For Rosemary, then 19, it was an unexpected salvation.

Her parents enrolled her in Belmont House, a convent school that followed a Montessori program. For the first time, Rosemary had a structured environment designed around her needs rather than around the performance standards of everyone else in her family. She thrived.

Her beauty and easy charm also caught the attention of the British press. In May 1938, Rosemary and her younger sister Kathleen were presented to King George VI and Queen Elizabeth at Buckingham Palace.

Newspapers plastered photographs of the smiling Kennedy girls across their front pages. Rosemary, in a white dress with tulle and silver embroidery, was described by the press as exquisite.

But the stability would not last. In September 1939, Britain declared war on Germany, and the Kennedy family fled back to the United States all except Rosemary, who was sent to Belmont House for her safety while her father remained in London. It was reportedly the happiest period of her life.

In November 1940, Joseph Kennedy Sr. was forced to resign as ambassador after his openly expressed Nazi sympathies and his public prediction that Britain would lose the war made him a diplomatic liability. He was recalled to America. Rosemary went with him, back into the competitive, high-pressure world she had finally escaped.

She did not recover from the transition. Ripped from her support system at Belmont House and thrust back into a household built around achievement and appearances, Rosemary regressed sharply.

She lashed out. She experienced seizures. Violent temper tantrums became frequent. Most alarmingly for her parents, she began breaking out of the convent school where she was now enrolled and wandering the streets of Washington D.C. alone at night.

The Kennedys were already living under the shadow of the 1932 Lindbergh kidnapping, in which Charles and Anne Lindbergh’s infant son had been abducted and murdered. For wealthy American families of that era, the fear of abduction was not abstract. Rosemary’s nighttime wanderings and what she might encounter, or who she might encounter terrified her father.

Joseph Kennedy Sr. made a decision. He told no one else in the family.

Her Father Orders the Lobotomy in Secret

The prefrontal lobotomy was, in 1941, being marketed to the American medical establishment as a revolutionary procedure. Its proponents claimed it could calm patients with severe behavioral problems, reducing agitation and outbursts through targeted severing of connections in the brain’s prefrontal cortex.

The operation was performed either by drilling into the skull directly or, in later variants, by entering through the eye socket with a sharp instrument. The broader medical community harbored serious reservations about the procedure. Most hospitals refused to perform it.

Joseph Kennedy Sr. ignored those reservations. He arranged for two doctors to perform the lobotomy on his eldest daughter. He did not consult his wife Rose. He did not consult any of Rosemary’s siblings. Some accounts allege that Rosemary herself was never told what the surgery would involve.

She was strapped to an operating table, conscious. Her head was shaved. The doctors began their work, asking her periodically to sing songs and recite prayers as they probed her brain — gauging the depth of the incisions by whether she could still respond. The procedure continued until Rosemary went quiet.

The attending nurse quit her job and left the medical profession.

The lobotomy destroyed Rosemary Kennedy. The vibrant 23-year-old who had danced at Buckingham Palace and filled diaries with descriptions of European royalty was gone. In her place was a woman with the mental capacity of a two-year-old unable to walk, unable to speak clearly, permanently and catastrophically damaged by an operation her father had authorized without her knowledge or consent.

The Surgery Destroys Her in a Single Morning

Joseph Kennedy Sr. had Rosemary transferred to a psychiatric hospital in upstate New York. He told the rest of his family almost nothing. Her siblings, who had spent their lives either competing against her or carefully including her, suddenly found her simply absent with no coherent explanation for why.

Eunice Kennedy, the sibling closest to Rosemary, would later say she had no idea where her older sister was for more than a decade. The public explanation offered by the Kennedy family was that Rosemary was away studying, training to become either a teacher or a social worker. Joseph Sr. initially maintained the fiction that she was doing well. After 1944, the family’s personal correspondence stopped mentioning her entirely.

In 1946, John Kennedy was elected to the House of Representatives and began the trajectory toward the White House that his father had always envisioned. As JFK’s political star rose, Joseph Sr. grew anxious that the truth of Rosemary’s condition might surface and derail his son’s ambitions.

He had Rosemary transferred again this time to an institution in Jefferson, Wisconsin, far from the family’s social network in the Northeast, far from anyone who might ask questions or arrange a visit.

He then spent years feeding the family excuses to discourage them from going to see her. He never visited her himself again. There are unconfirmed rumors that John Kennedy stopped by during his 1960 campaign trail, but this has never been verified.

Joseph Kennedy Sr. died in 1969 having never seen his eldest daughter again after the day he had arranged for her to be operated on.

Her Siblings Learn the Truth and Fight Back

When Rosemary’s brothers and sisters finally learned what had been done to their sister, they were horrified. What followed was not grief alone but action a sustained political and philanthropic campaign that would reshape American policy toward people with disabilities, driven in large part by the knowledge of what had happened to a woman their father had hidden from them for twenty years.

As President of the United States, John F. Kennedy enacted legislation specifically designed to fund research and support programs for people with intellectual disabilities — a cause that had personal resonance for him in a way the public did not yet understand. His administration’s work laid groundwork for federal programs that would outlast him.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver went further. She earmarked a portion of the Kennedy Foundation’s funds for research into mental and physical disabilities. In 1962, she opened Camp Shriver — a retreat designed to give disabled children a normative, joyful summer camp experience. Children with a range of mental and physical disabilities were invited to swim, play, and compete. Within a few years, the camp had evolved into something larger.

It became the Special Olympics.

The organization that now serves more than six million athletes in 190 countries was born, in part, from a family’s reckoning with what had been done to Rosemary.

Rosemary Returns, But Never Fully Comes Back

After Joseph Kennedy Sr.’s death in 1969, Rosemary was gradually brought back into contact with her family. She visited relatives. She joined siblings on holidays. She met her many nieces and nephews, who remembered her with warmth.

She never fully recovered. She walked again, eventually but she never regained the ability to speak clearly. The woman who had been described as exquisite and charming, who had danced at Buckingham Palace and wept with happiness at Belmont House, remained profoundly limited for the rest of her life. She found being around her mother difficult. But she appeared, in the accounts of those who knew her in these later years, to find real contentment in smaller moments.

Rosemary Kennedy died on January 7, 2005, at the age of 86, of natural causes. Her siblings were by her side.

In the words Senator Ted Kennedy used to describe his oldest sister, Rosemary taught us the worth of every human being. What she taught the rest of America came at a cost no one had the right to impose on her.

The nurse who was in that operating room in 1941 walked out and never went back. The patient on the table had no such option.